Discovering the Life of Gordon Merrick ’39, an Unlikely Gay Novelist

Joseph M. Ortiz *03’s biography is titled ‘Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel’

When Gordon Merrick ’39 arrived at Princeton in the fall of 1935, he had little intention of becoming a novelist. His passion was for the stage, and he immediately threw himself into the University’s theater scene. With his good looks and dulcet voice, he was a natural acting talent, and before long he was the star of Theatre Intime, by then a breeding ground for Broadway actors. Buoyed by his campus fame, Merrick left Princeton after his junior year to pursue a Broadway career, eventually landing a coveted role in The Man Who Came to Dinner. Merrick’s future, though, was not as an actor, but as one of the most important — and most controversial — gay novelists of the 20th century.

The story of Merrick’s literary career is a circuitous and unexpected one. After a few years on Broadway, Merrick dabbled in journalism before being recruited by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the precursor of the CIA) during World War II. The OSS valued his acting ability (and his fluent French) and assigned him to a counter-espionage mission in the south of France. The experience became the basis of Merrick’s first novel, The Strumpet Wind, which was published in 1947. The novel garnered positive reviews — except from The New York Times, which criticized Merrick for being a “scrupulous moralist who tries hard to see both sides” of the war.

“You deserve much credit for what you have done for the gay community. You have made me realize that somewhere there is hope of finding someone special to share my life and love with.”

— Anonymous fan in a letter to Gordon Merrick ’39

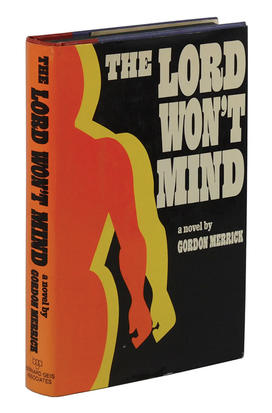

While Strumpet established Merrick as a respectable postwar novelist, it was another semi-autobiographical novel, written two decades later, that made a true literary splash. In 1970, Merrick’s fifth novel, The Lord Won’t Mind, hit the bookstore shelves. Unlike his previous novels, which had minor gay characters, this one was centered on a gay man: Charlie, a Princeton-educated actor who falls in love with another man. Rather than being coded or hidden, the novel’s gay subject matter was boldly highlighted — “the first homosexual novel with a happy ending,” according to the advertisements. Surprisingly, Lord was an immediate bestseller. It stayed on The New York Times top 10 list for an impressive 16 weeks, and the paperback edition that followed was even more popular. Afterward, Merrick wrote eight more gay novels, all published in paperback and distributed to a mass readership. When he died in Sri Lanka in 1988, he was unquestionably the world’s most commercially successful writer of gay fiction.

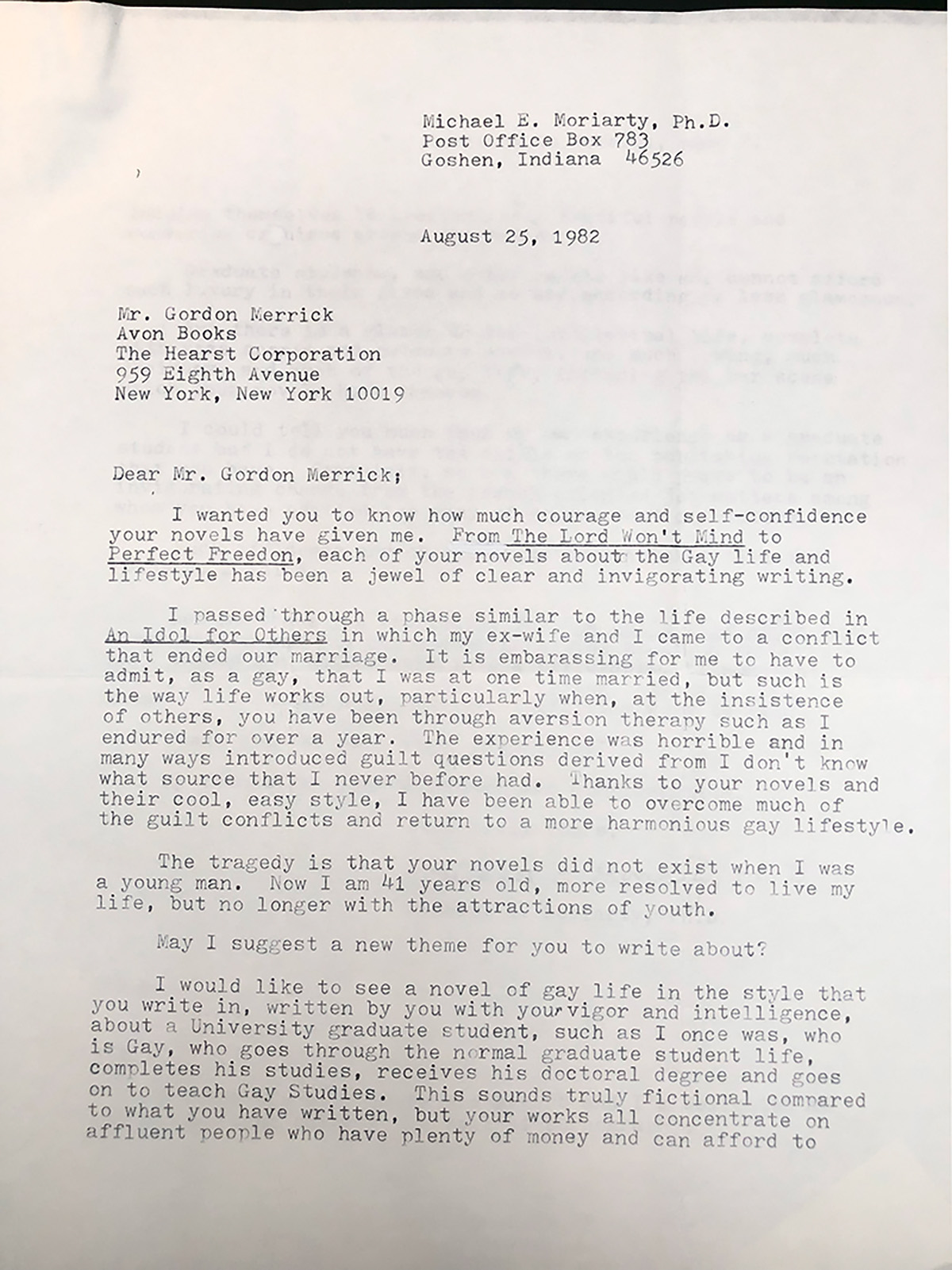

I personally discovered Merrick’s novels as a gay teenager in New Mexico in the 1980s, when one day I stumbled upon Lord at the local Waldenbooks. (This was a common scenario for Merrick’s readers, thanks to his publisher’s shrewd distribution strategy.) However, it was not until years later — as a graduate student at Princeton — that I learned about Merrick himself. Princeton’s Special Collections Department contains the Gordon Merrick Papers, a large archive of manuscripts, letters, and photographs that were donated to the University by Merrick’s surviving partner, Charles Hulse, after his death. I began researching the archive as a distraction from my dissertation on Shakespeare, but the wealth of materials — and the peculiarity of Merrick’s life — turned this distraction into an obsession. Eventually, my research became the basis of a complete biography, Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel, which was published by Lexington Books in 2022.

Among the archive’s many treasures is its collection of fan mail sent to Merrick in the 1970s and ’80s. Although Merrick was routinely ignored by literary critics (including gay critics) who deemed his work too idealistic or sexually explicit, he had a large and diverse readership who devoured his novels. These included gay men of all ages and backgrounds, as well as a few straight women. Taken together they offer a rare glimpse into the lived experiences of gay men in the period, particularly those who lived outside the meccas of New York and San Francisco. “You deserve much credit for what you have done for the gay community,” wrote a 21-year-old reader in Dorchester, Massachusetts. “You have made me realize that somewhere there is hope of finding someone special to share my life and love with.”

The archive also reveals a previously unknown aspect of Merrick’s novels — the fact that all of them contain autobiographical episodes. Both before and after Lord, Merrick routinely drew from his life experiences, including his time at Princeton. For example, in One for the Gods (the sequel to Lord), he re-creates Princeton’s undergraduate theatrical scene in the 1930s, suggesting that it was a relatively safe space for gay students. Other scenes derive from Merrick’s Broadway career. In these episodes Merrick often depicts the darker side of New York’s theatrical world, which had its share of struggling actors and predatory directors. Merrick included here veiled (and sometimes not so veiled) portraits of many Broadway luminaries, such as Moss Hart, Clifton Webb, Cole Porter, and Noël Coward.

Some of the most fascinating autobiographical moments in Merrick’s novels are those based on his work as an OSS agent. The experience profoundly changed Merrick’s outlook on life, in part because it showed him other ways of living in the world as a gay man. In France, Merrick found that he did not have to guard his sexuality the same way he did in America — including from his OSS commanders, who knew he was gay but apparently did not care. “I don’t know why they didn’t get rid of me on the spot,” Merrick said in an interview decades afterward. “I guess they figured that if I was going to be that relaxed about it, then it couldn’t be a very serious problem.”

Ideally, the story of Merrick’s life will prompt other historians and literary critics to explore those aspects of LGBTQ+ history that have not been fully documented or have been hidden from view — like gay men who were allowed to serve in World War II. In his review of Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel, the writer Andrew Holleran states that the history of Merrick “ends up being a fascinating history of arguments over just how gay people were to be portrayed” in the decades following Stonewall. As recent debates over LGBTQ+ films and plays have shown, such arguments are far from being settled.

Joseph M. Ortiz *03 is department chair and professor of English at the University of Texas-El Paso.

No responses yet