In Documentary, Daniel Mendelsohn *94 Dispels Holocaust Myths

‘It really makes this country’s inaction all the more appalling,’ Mendelsohn says

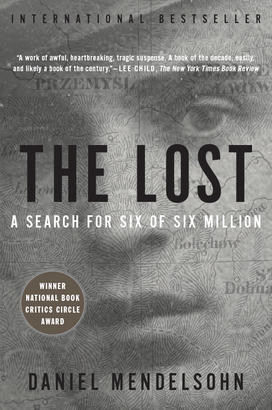

Daniel Mendelsohn *94 grew up hearing stories about his great uncle’s family in Eastern Europe and seeing their photos in family albums. On the back of each photo, Mendelsohn’s grandfather had written: “Killed by the Nazis.”

When he turned 40 in 2000, Mendelsohn found himself wondering whether it was possible to find out more. “I was no longer satisfied with ‘Killed by the Nazis,’ and I thought, ‘No one just disappears, no one is a statistic. Something specific happened to these six people.’”

That story is now also part of a new three-part PBS documentary, The U.S. and the Holocaust, which premieres Sept. 18 and is directed by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, and Sarah Botstein. According to Mendelsohn, who has seen a final cut, it amounts to “a very powerful and disturbing reckoning for this country.”

“When I was growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, the standard line that you heard about what the U.S. did was: ‘Nobody knew,’ right?” Mendelsohn says. Americans always claimed they didn’t know about the concentration camps overseas, about gas chambers and mass shootings, until soldiers liberated the camps in 1944 and 1945, he says.

“This documentary makes it very clear that at every level of the U.S. government, they knew everything that was going on before, during, and after, and it really makes this country’s inaction all the more appalling,” he says.

Mendelsohn’s great uncle wrote desperate letters to family in the U.S., including to Mendelsohn’s grandfather, looking for help getting a visa out of Poland. But it was already too late to get a visa — the family of six would all die at the hands of the Nazis. Mendelsohn says he was “electrified” when both he and his mother were asked to participate in this documentary, because it gave his relatives a new life.

“These people were killed in a way that was meant to erase them from the record ... so I always think any gesture that reanimates them and makes people aware of who they were and that they had these lives is so important,” Mendelsohn says. He became emotional when he saw the first promotional video for the documentary because it shows a photograph of his family members in the first frame.

“Millions of people will know who they are now, and I think that’s kind of a bit of a moral victory after what was done to them, because they were meant to disappear without a trace, and this is a way of pushing back against that.”

The documentary helps viewers understand the roots of the Holocaust, from the rise of authoritarian figures and national socialism to the denigration of the press and an encouragement of political violence. Mendelssohn says he sees those forces at play today, too, concluding: “History is repeating itself.”

Watch a trailer for The U.S. and the Holocaust:

3 Responses

Harold Bursztajn ’72

2 Years AgoPandemic Coincident Anti-Semitism as Grief Work Avoidance

The COVID pandemic coincident resurgence of anti-Semitism, racism, and aggression is a stark reminder of its role as the canary in the coal mine of fascism. That coal mine provides fuel for escapes from the work of grief via a flight to shaming, blaming, and scapegoating. Remembrance of family history is a more courageous and healthier path of grief work

Laure Bennett

2 Years AgoImportance of Family History

I have read The Lost three times and will never forget Daniel’s desire to find his lost family for his existing family. Our family too has a Jewish history difficult to uncover. Although we are not yet linked to the Holocaust, I have read many accounts of survivors and I am watching Ken Burns’ PBS series, an excellent recounting of the truth of the what was happening in Europe, known in our country, yet dismissed on so many levels. I hope to continue impressing upon our sons, daughters, and grandchildren the importance of the truth in all things, but especially for our Jewish existence, the truth of our family history.

Thank you so very much.

Norman Ravitch *62

2 Years AgoA Repeat Is All Too Possible

Professor Mendelsohn has a lot of courage to relive these events as he has. I don’t know how many books about the Holocaust will finally make another such terror less possible. This country and some others as well seem to be reliving many of the reasons for the rise of fascism and National Socialism. I am not optimistic. I want to finish anything I write — an article, a letter, a comment, whatever — with this phrase: Fight fascism!