Economics: The Price of Our Energy

Study documents consequences for babies born to mothers living close to fracking

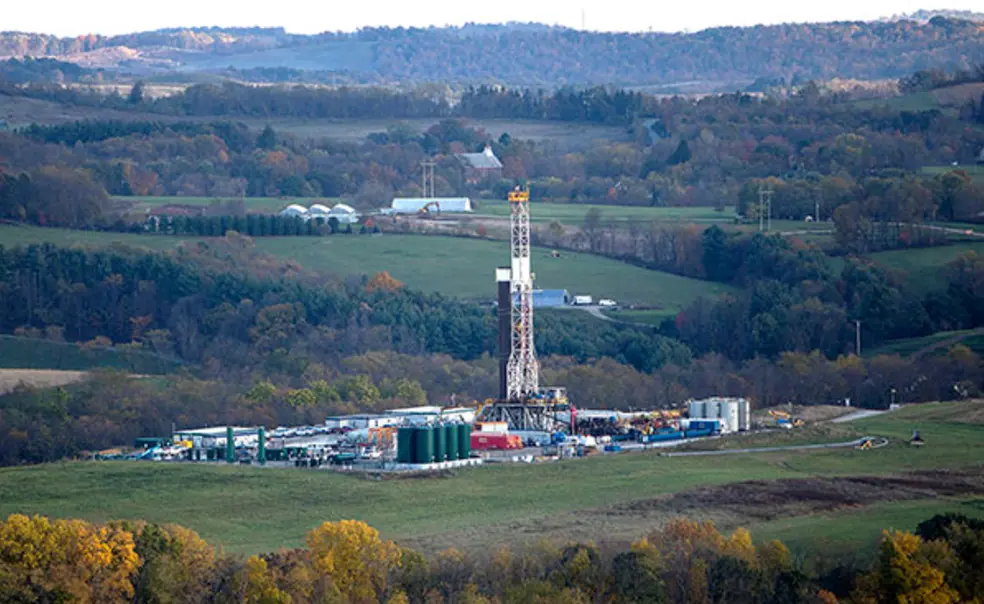

The United States is in the midst of a fracking boom. Short for “hydraulic fracturing,” the technique for exploiting deep deposits of natural gas and oil was virtually unknown before 2000. Now it accounts for more than two-thirds of all oil and natural gas production in the U.S., upward of 6 million barrels of oil and 50 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day. For rural communities, where most of the fracking takes place, a potential source of pollution has arrived in their backyards.

The effects of fracking must be examined, says economics and public affairs professor Janet Currie *88, because “most sources of pollution have been around for decades. [With fracking], you have these rural areas with no heavy industry that suddenly have heavy industry.” Currie, who is the director of Princeton’s Center for Health and Wellbeing and co-director of the Program on Families and Children at the National Bureau of Economic Research, has spearheaded a new study on the health effects introduced by fracking. Published in Science Advances in December, the paper by Currie and two colleagues sounds an alarm for those living close to the wells.

Environmentalists have long raised concerns over the toxic fracking fluid, which is injected deep into the ground to crack open gas and oil deposits. “If everything is functioning as it should, there shouldn’t be any way for it to leak into the groundwater,” says Currie. “Of course, things don’t always work as they should.” Less attention has been placed on the air pollution fracking might cause. In addition to the fumes from truck traffic, the volatile chemicals used in the process could potentially diffuse into the air to be inhaled by nearby residents, according to Currie.

To gauge the consequences of air and water pollution, Currie and colleagues from the University of Chicago and UCLA examined data on newborns across Pennsylvania, a state that has seen a particularly large fracking boom. The researchers obtained a dataset with more than 1.1 million births in the state between 2004 and 2013. With the help of Princeton University Library’s Global Information Systems team, they were able to code each birth to find its distance from the nearest fracking well.

They then compared birth weight and other factors — both for babies born near and far from fracking wells and also for babies born to the same mother before and after a nearby well came on line. Low birth weight can be both a cause and an indication of a range of health problems, including asthma and cognitive and behavioral issues. Birth weight is “the best summary measure we have for large population health,” Currie says.

The researchers found a stark difference for mothers living within about a half mile of a well. Babies born to those mothers were 25 percent more at risk of having a low birth weight — from a 6.5 percent likelihood to an 8.1 percent chance. Additionally, they found babies were slightly more likely to exhibit other problems, such as premature birth and congenital abnormalities.

The researchers, however, also found that the effects diminished sharply as distance from fracking wells increased, with no effects found after 1.9 miles. That suggests that much of the pollution from fracking sites could be mitigated by situating them away from residential areas. “It’s not likely that we are going to shut down all fracking in the U.S.,” Currie says. “If you are going to protect people’s health, it’s better to know how close you can be before it becomes a problem.”

The study controlled for factors such as race and marital status, but not income, since birth certificates don’t include that information. If anything, says Currie, the study understates the effects of fracking, since income of families close to wells might increase due to higher wages from an improved economy or payments for mineral rights. In that case, the effects of pollution could be offset by benefits, including better housing, medical care, and less financial stress.

Until fracking chemicals and their effects are better understood, Currie recommends zoning that prohibits new wells within 2 miles of populated areas. In more remote areas, such as North Dakota, she advises building worker housing outside of a 2-mile radius. For those already living near fracking wells, however, there may be little recourse. Rather, states might consider setting up a fund to help them relocate, as has been done with other environmental hazards. “If you can separate out the polluting activities from where people are living,” you would have fewer health effects, Currie says. “Places that have high population density may want to make different decisions about whether they allow fracking at all.”

3 Responses

James S.M. French ’62

7 Years AgoFracking Is Not New

Having graduated from Princeton in 1962 with the B.S.E. degree and a concentration in geological engineering, I was interested in the article about Professor Janet Currie *88’s research (Life of the Mind, March 21). The article states that “hydraulic fracturing ... was virtually unknown before 2000.” In my studies of petroleum engineering in 1960 and 1961, hydraulic fracturing was well known even then, and we were taught how it was being widely and effectively used. Our textbook, published in 1956, also describes fracking.

It is a widely held misconception that fracking is a new process. It is not. There are extensive studies, including by the Obama EPA, showing no harmful effects of fracking. It should also be known that the primary materials used in fracking are sand and water. Authors of articles need to be most careful with all of their facts.

Hugh MacMillan ’94

7 Years AgoFracking’s Impact

After graduating from Princeton in 1994 with an A.B. in mathematics and earning a Ph.D. in 2001 in applied mathematics at the University of Colorado, I spent time in recent years focused on the “Obama EPA” study that James French ’62 cited as “showing no harmful effects of fracking” (Inbox, May 16).

As Mr. French knows well, the modern spat over hydraulic fracturing began in earnest in Alabama. Energen, where he served as a director from 1979 to 2011 (according to Bloomberg), succeeded in fending off complaints about water contamination from Alabamians living near his company’s fracking operations. The Reagan, Bush, and Clinton EPAs chose to not regulate fracking-fluid injections as underground injections subject to the Safe Drinking Water Act. Using language then-Senator of Alabama Jeff Sessions had introduced in 1999, this practice was codified as law in 2005, the so-called “Halliburton Loophole.”

Perhaps Mr. French confused the draft EPA study (July 2015) — which stated EPA did not find “widespread, systemic impacts to drinking water resources” — with the final version (December 2016), which deleted that line on the advice of the EPA Science Advisory Board. Marketplace, the popular radio show, revealed that the controversial and unsupported top line had been a rather late addition to the draft.

Why? The answer goes to the heart of the disconnect between energy policy and climate policy: Maximize oil and gas production, or maximize what we keep in the ground? Hundreds of billions in oil and gas industry debt ride on the answer. So too, the stability of our climate. Indeed, this is not new.

Norman Ravitch *62

7 Years AgoFracking and Health

It has become obvious that conservative pro-lifers love fetuses but not living children. So don't expect any policy to obviate the dangers to children from fracking.