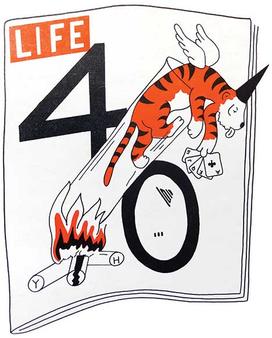

From the Editor: How ’40 Witnessed History

With the recent death of Marshall Forrest, ’40’s last known living member, the class column in PAW will end. Marshall’s memorial appears on page 51; a senior-class photo is on page 35.

From its first day on campus, the class noted changes taking place in town and abroad — and it seemed to approach everything with a self-deprecating sense of humor. There was much discussion of an article in a Sarah Lawrence publication describing the sons of “Old Nausea”: “They have a distinctive way about them which is often overdone as far as the short trousers, loud-checked coats and pipes are concerned,” the article stated. “Good dancers, although some tend to be a bit violent in grape-vine steps and ‘side-twinkles.’ ” [Note to self: Get video of side-twinkles.]

Edgar Palmer was redeveloping downtown: “The Old Nass was no more,” the ’40 history reports, “[b]ut it was the sumptuousness of the new Yankee Doodle Taproom which made us quickly forget … .” Palmer’s vision led to the Princeton we know today — but forced the relocation of most of the town’s Black community in the process.

The class sometimes poked fun at its lackluster academic reputation, but time proved it wrong. In fact, 1940 produced one of Princeton’s most important academic leaders: future Princeton president Robert Goheen, who would transform the University with coeducation and construction. Others also made lasting marks: pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, who counseled countless parents through his books and syndicated columns; William Colby, former director of the CIA; and U.S. Sen. Claiborne Pell, whose legislation helped low-income students attend college. The Pell grants were named to honor him.

Sophomore year was known for its “varied accounts of the experiences of three Juniors who made a round-trip to Bermuda at the expense and chagrin of the Furness Line,” the history states, but the junior-year report notes Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia. (Another invasion also drew attention: the attack of Martians in nearby Grover’s Mill: “While eminent members of the psychology department found themselves hoisted by their own petards, frantic mamas swamped the local Western Union office and the week-ending sons of Old Nassau finally found themselves provided with an excuse to violate the 12:40 deadline at Sarah Lawrence.”)

As seniors, the students acknowledged the changes taking place around them: from a campaign for “radical changes in the Club system” at home to the presence of the German army near Paris.

“On the eve of possibly greater changes at home and abroad,” their history says, “we can only hope that the next revolution will be less bumpy and that the Class may come back in 1960 to its 20th reunion in a less chaotic world.”

No responses yet