Essay: Memories of Princeton Past Through a Child’s Eyes

Many members of the Class of 1976 had an existing connection to Princeton. I was among them, for my father had been an assistant professor of civil engineering from 1962 to 1966. However, unlike some classmates whose fathers had been students, I arrived as a freshman with few preconceived notions of undergraduate life — accurate or otherwise. Instead, I brought memories of some of those who form the nexus between undergraduate and community life, namely faculty members and their families.

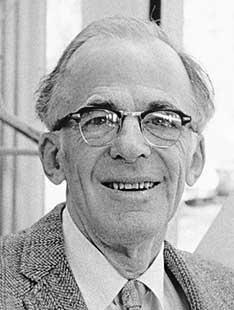

While growing up on Murray Place I attended Nassau Street School, subsequently known simply by its address, 185 Nassau Street, and now as part of the Lewis Center for the Arts. There I made friends with the children of several other professors, including the late David Billington ’50, professor of civil engineering, and Thomas Kuhn, professor of the history and philosophy of science. I remained in touch with both of those friends, but am closest of all to Lydia Spitzer, youngest daughter of the late Lyman Spitzer Jr. *38, chair of astrophysics, and his wife, Doreen Canaday Spitzer.

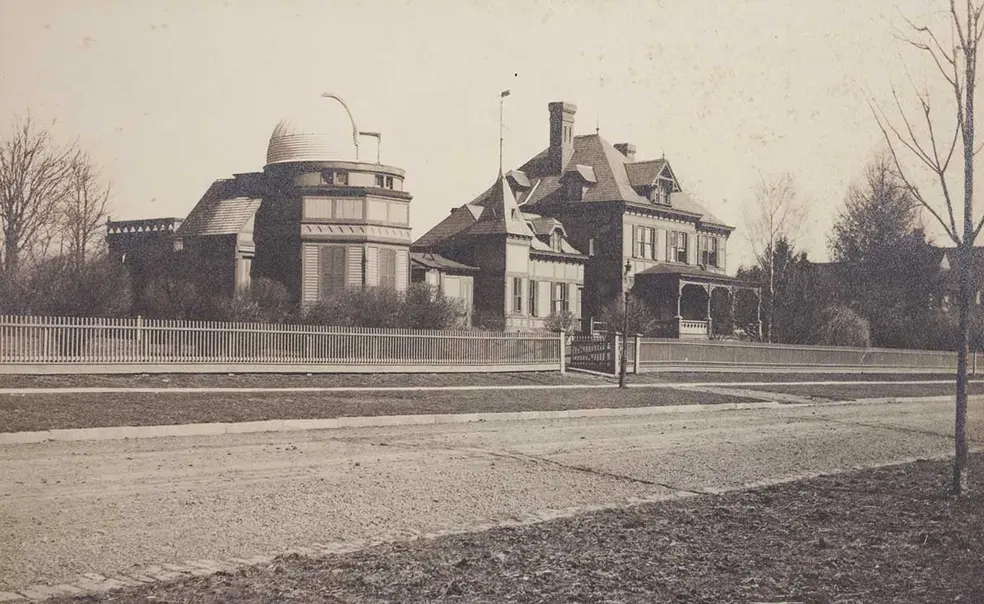

As an impressionable 8-year-old just transported from suburban Pittsburgh, I was first struck by the Spitzer home. It was an enormous house that loomed over the corner of Washington Road and Prospect Avenue for nearly a century until being replaced by the new home for the School of Public and International Affairs in 1963. It even had a name, the Observatory of Instruction, which was apt if odd, for where any normal home of its era would have had a carriage house or barn, it had an attached observatory.

Legend had it that the house was built in 1877 to entice famed solar spectroscopist Charles Augustus Young to Princeton from Dartmouth with the knowledge that he disliked rain — not only because clouds obscured the heavens, but because Young hated getting wet. By residing in a home complete with classrooms and observatory attached, Young never needed to venture far.

While the attached observatory was no longer used for instruction, it had a functioning telescope to which Professor Spitzer occasionally led family expeditions to view the stars. Access to it was through his office, from which Lydia and I were otherwise strictly forbidden. Perhaps there were early drawings of the Hubble Space Telescope or Model C stellarator, not to mention secrets of sonar, spread out across the desk.

Mrs. Spitzer reigned supreme over the rest of the house, with its double parlors, front and back staircases, separate butler’s and food pantries, empty servants’ quarters, and enormous attic. Lydia’s bedroom windows were conveniently located just above the front porch. On its roof we picnicked, read books, sang songs, danced, and told protracted tall tales to students walking by.

Otherwise, we did not have a great deal of contact with undergraduates. There was a babysitting service called “Tiger Tot Tenders,” from whose members we learned how to play poker and provide accompaniment on piano to their guitars. My parents occasionally took us to watch Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 play football or Bill Bradley ’65 play basketball. I confess that what I remember best is the night a basketball player lost his contact lens. Contacts were rare and expensive in those days, and the sight of a dozen giants gingerly crawling around the court until they found it was remarkable. I have no idea who won the game.

Our only other childhood interactions with students consisted of going door to door on Prospect Avenue in search of the Spitzers’ beagle Benjie. No undergraduate living or dead has enjoyed life on the “Street” more. After going AWOL around 10 p.m. on a Saturday, Benjie was usually home 12 hours later, belly dragging on the ground. However, the chef at Dial Lodge was a particularly soft touch, and that was where we first went if Benjie was still “sleeping it off” on Sunday at noon.

In the spring of 1963, Lydia’s and my third-grade class watched from her family’s backyard as Corwin Hall was moved on rollers to its present site. Mrs. Spitzer sold choice seating to benefit her alma mater, Bryn Mawr, but we watched for free. Several months later, the Observatory of Instruction was razed. During those last few months, Lydia and I were turned loose by her mother to paint and draw whatever we liked on walls not visible to guests. I recall that exhilarating madcap freedom as though it were yesterday.

From Prospect Avenue the Spitzers moved to a home on Lake Carnegie, where Professor and Mrs. Spitzer lived until their deaths. It was in their new dining room that their old grace (“Rub a dub dub, thanks for the grub!”) continued to be said by the youngest child present, followed by Professor Spitzer’s solemn pronouncement, “Life is uncertain. Eat dessert first.” I don’t believe we ever did, but “Hope springs eternal!” is another expression I learned from him.

Dinner was always in the dining room, and conversation always on a high intellectual and cultural plane. Disputes were settled by Professor Spitzer calmly reaching back (seemingly without looking) to a set of Encyclopedia Britannica behind his chair to “see what the experts have to say.” After I returned to Princeton as an undergraduate in 1972, I continued going to dinner from time to time. Professor Spitzer needed no expert opinions the evening he announced he had made it onto Richard Nixon’s “enemies list” and was very pleased indeed.

While Professor Spitzer was unfailingly kind to his youngest daughter’s friend, his mind was “in the stars,” and he was usually at work. In his absence Mrs. Spitzer was an exceptional leader of expeditions and creator of fun. Impromptu recitals, puppet shows, and amateur theatrics were everyday occurrences. She saw to it that Lydia and I had a canoe for exploring the lake and its islands. She gave me my first ski lesson on the snow-covered slope leading to the shore.

Professor Spitzer was a noted mountaineer, and Mrs. Spitzer’s athleticism and spunk were no less impressive. As newlyweds they had “herringboned” up Vermont’s Mount Mansfield in order to ski down before there were lifts built at Stowe. One memorable Saturday both Spitzers helped Lydia and me to clear a patch from the frozen lake for skating. She and I cavorted about the center while her parents danced gracefully around the edge to the strains of Richard Strauss from a portable record player.

It was in their new dining room that their old grace (“Rub a dub dub, thanks for the grub!”) continued to be said by the youngest child present, followed by Professor Spitzer’s solemn pronouncement, “Life is uncertain. Eat dessert first.”

As a teenager I began to be aware of Doreen Canaday Spitzer’s tireless volunteer efforts on behalf of the Princeton Gilbert and Sullivan Society, the Princeton University Art Museum, the Unitarian Church, and Bryn Mawr. Even later I realized she was the sole heir to a substantial fortune from the manufacture of Jeeps and an anonymous supporter of multiple cultural institutions as far flung as her native Toledo, Ohio, and the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Greece.

Mrs. Spitzer’s elegance and accomplishments may have been a natural outgrowth of her upbringing, but her warmth and generosity were all her own. I have saved a trove of letters signed “OMS” for Old Mother Spitzer, as she liked to be addressed. When my medical school schedule in New York made it impossible to collect my marriage license from Princeton Borough Hall in time for the ceremony, she dropped everything, crying, “The show must go on!” and did it for me.

Professor Spitzer passed away in 1997; Mrs. Spitzer, in 2010. They donated the house on the lake to the University for the benefit of the astrophysics department, and through a series of fortunate events, my husband and I now live there. There we are constantly reminded of both an exceptional university and an exceptional community, and the extraordinary individuals who contribute to both.

3 Responses

Robert Monk *63

4 Years AgoPleasant Memories of the Spitzers

Margaret Ruttenberg ’76’s essay (“Memories of Princeton Past Through a Child’s Eyes,” September issue) opened for me a flood of pleasant and delightful memories of weekends living in the Spitzers’ home. In the fall of 1959 my wife and I were offered the opportunity to stay with the Spitzers’ two youngest daughters over a weekend. So began our distinctive adventure sharing a number of weekends with the girls over the next couple of years while Professor and Mrs. Spitzer were out of town. With a maid and cook caring for the home it was indeed an attractive and privileged opportunity. Having grown up in modest West Texas homes, my wife and I found our graduate study lives being exponentially expanded as we lived and briefly observed life in this gracious home.

As Dr. Ruttenberg indicates, the house was an enormous, distinctive, and unusual faculty home of many rooms with an attached observatory, empty servant’s quarters, and a large attractive yard. Exploring the home was indeed an adventure when accompanied by two delightful, inquisitive, smart, and fun girls. We were entertained by their original dramas on the stage in their large, well-equipped playroom, led throughout the house playing hide and seek, and serenaded at bed time with Gilbert and Sullivan recordings as the girls learned the words of each musical so they might participate in summertime Princeton Gilbert and Sullivan Society presentations. For my wife and I to participate briefly in the family life of the Spitzer children was indeed a welcome interlude from our graduate school grind. Professor and Mrs. Spitzer were most gracious, friendly, and trusting in their employing us for those weekends. Our privileged experience in this home is a most pleasant memory of our Princeton days.

William Hollinshead ’64

4 Years AgoThe Remarkable Spitzers

I expect Margaret Ruttenberg ’76’s memories of the Spitzers and the Observatory of Instruction (Princetonians, September issue) elicited many others from those of us lucky to know them. Although not a “Tiger Tot Tender,” I taught at Miss Mason’s School and was asked to stay with the two youngest Spitzers when their parents were away in 1961 and 1962. I recall joyous meals, new songs, and expeditions in the Spitzers’ Oldsmobile (a rare dividend when we weren’t allowed cars).

All that prepped me for 50 years married to a strong woman (Bryn Mawr ’69), three feisty daughters, and a career in pediatrics. My wife and I caught up later with Doreen Canaday Spitzer at Princeton, Bryn Mawr, and Athens. Like Dr. Ruttenberg, I graduated with many rich memories beyond the dorms, classes, teams, and clubs. The Observatory was the most exciting place on Prospect Street!

Jonathan Young ’69

4 Years AgoDancing to Strauss

In the excellent article on Lyman Spitzer *38, Margaret Ruttenberg ’76 mentions Dr. and Mrs. Spitzer dancing to the strains of Richard Strauss.

The piece in question is not specified, but I will go out on a limb here and voice my suspicion that the composer was one of the Johann-Joseph Strauss family of Vienna, rather than Richard Strauss of Bavaria, whose output was primarily opera and lieder.