Essay: Writing Carole King’s Life, Thanks to Triangle Club

Six years ago, I found myself sitting across from legendary singer-songwriter Carole King. I was one of several writers being considered to adapt her life story for the Broadway stage. Until then I’d had a long career in TV and film. I started out as a writer for Saturday Night Live right out of college, and later wrote screenplays and humor pieces for magazines until Woody Allen asked me to co-write the screenplay of the 1994 film Bullets Over Broadway. After that, I wrote and directed the films Emma, Nicholas Nickleby, and Infamous.

As King and her fellow songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, also to be featured in the show, sized me up, one of them said, “You’ve never written a musical before. Why should we trust you to write ours?” My answer: the Princeton Triangle Club.

In fact, I had written musicals before, but they were performed closer to Wawa than Sardi’s: I wrote two Triangle shows. After landing the job to write the book for the musical Beautiful, which tells the story of how King became one of the most successful singer-songwriters of her time, I realized that apart from the budget, having written two musicals for Triangle was not much different from doing Beautiful. In fact, they made it possible.

Everything I used to write Beautiful, I learned from my Triangle shows: sitting in the audience and listening for what works and what doesn’t and when it doesn’t, quickly finding a way to change it. It was at 185 Nassau St. and McCarter Theatre that I first learned not to be sentimental about something just because I wrote it.

At Princeton, I performed in several Triangle shows before writing one. The first show I wrote, Happily Ever After — for which I did the book and co-wrote the lyrics with David E. Kelley ’79 — received a fairy-tale reception from The Daily Princetonian. My second show, String of Pearls, which I wrote senior year, was more string than pearls. Our first run-through ran longer than Lawrence of Arabia. The officers of the club brought me into a room that in my memory had one lightbulb hanging from a fraying cord. They told me I needed to cut the show — a lot. I was shocked by this impertinent notion. Of course, they were right. This lesson stayed with me — by the time Beautiful opened, it was 20 minutes shorter than when we started.

String of Pearls was scathingly — and rightly — dismissed in the Prince. And that is its own necessary training. Whether it’s the Prince or The New York Times, you have to learn to leave your room and either hold your head up or keep it down — but keep going.

For Beautiful, I interviewed the songwriters about their lives over many hours, then selected the most interesting period and wrote the story and dialogue, choosing songs of theirs that helped the narrative. During the five years we worked on the show, I always was rewriting. When Beautiful was performed at the Curran Theater in San Francisco for four weeks in the fall of 2013, I rewrote every day, fixing jokes that didn’t work, rearranging the order of the songs, adding new scenes, ditching old ones. On our opening night on Broadway, my wife gave me a T-shirt that said 58, the number of drafts I had done.

Since opening in January 2014, Beautiful has broken the box-office record at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre 14 times and earned seven Tony nominations, including one for my book. I lost to Robert Freedman’s highly praised A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder. He was expected to win, but I prepared a speech just in case. (I can’t stand those people who come to an awards show and then act shocked when they win.)

The Tony people are strict about your speaking time — you have 90 seconds from the moment your name is called. I have been blessed with many mentors, teachers, and fellow writers, supportive friends and family, all of whom made my script possible. There were so many people I wanted to thank, and every time I practiced the speech it was too long. So the odious task of cutting began. But one name I knew I could never cut was the Triangle Club. I owe an unpayable debt not only to the inspiring students who made up the casts and crews, but to the generous and visionary board of directors who underwrote my shows on faith, just because that’s what the club stands for.

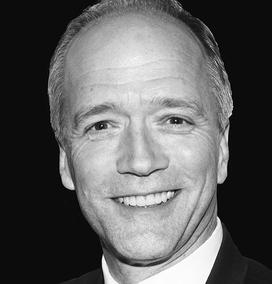

Douglas McGrath ’80 is a playwright, filmmaker, and essayist who lives in New York City with his wife and son.

No responses yet