Alexis Okeowo ’06 was a 2006–07 Princeton-in-Africa fellow at The New Vision newspaper in Uganda. She is writing a travel memoir about her two years in Africa.

I was riding in a public matatu, essentially a glorified minivan, when the moment I had been dreading finally arrived. We were approaching my stop, the market in front of my apartment, and I needed to alert the driver that I would like to disembark. “Stage,” I said weakly, using the term I had heard other passengers use at their own stops. The fare-taker nodded and then asked me something about where exactly I wanted to get off. But he put the question in the Ugandan language Luganda, and I could respond only: “English?”

He immediately stopped counting his money. The other commuters halted their conversations, and they all silently watched me as I sighed, then awkwardly climbed out of the van. Until I had spoken, none of the other passengers had suspected I was foreign, and I liked moving around unnoticed. But now I had been exposed as that rare creature: an African-American living in East Africa.

My family hailed from Nigeria, though I was born and raised in the United States. When I would explain this to Ugandans, the usual reply, typically delivered with a wide smile, was, “Ah, OK. You are still one of us!”

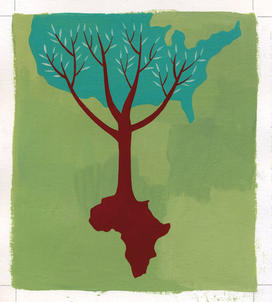

I had left my family behind in familiar Alabama to move thousands of miles to a small African country I knew little about so that I could take a fellowship with Princeton-in-Africa. Uganda in 2006 was a fresh change — gorgeous, warm, and welcoming. Still, the northern region was hovering between the end of a two-decade civil war that cost tens of thousands of lives and displaced 2 million others, and the start of a potential peace. It was a time when anything could happen in Uganda, and I was excited to be falling into a complete unknown. I didn’t know that I would be hovering personally during that time, too, between being an American with African roots and simply being an American expatriate.

“You are a black American?” 13-year-old Charles Ojok disbelievingly asked me one sun-drenched afternoon. Charles is a former child soldier, kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army — a Christian militant group — and trained at the age of 9 to commit rape and murder on his own neighbors. But on that day, he was like any other teenage boy, dressed in a T-shirt, chewing on a pencil that shed yellow flakes onto his clothes.

We were sitting on the porch of a house that sheltered former soldiers in the capital, Kampala, and as he asked the question, his once-shy housemates bounded out of the door to peer at me. They pulled me to a computer they shared and excitedly showed me the American hip-hop videos on the screen. I reveled in the irony — after a long morning of my trying to engage the boys in conversation, they now were trying to relate to me. I sat down at the computer and muted the music as I asked them whether they had ever learned about other notable black Americans. Martin Luther King Jr.? Malcolm X? They looked at me with blank smiles. As I searched on Google for a black-history Web site, Charles and his friends lost interest. I got the frustrating feeling, again, that Ugandans thought most black Americans were rappers, athletes, or gangsters, and that there was not much I could do to change that perception.

I had read about the very small number of African-Americans in Africa before I moved to Uganda. Most of the thousands of expatriates living in the country were white Americans or Europeans who worked for nonprofits, embassies, travel companies, or religious groups. When I arrived, Ugandans immediately assumed I was one of them, and were confused when they found out I wasn’t. In the market, on the street, in a bar, well-meaning but curious strangers would inquire why I looked African yet did not sound African.

I desperately wanted to be regarded as another African, to latch onto my Nigerian roots, but that didn’t really happen. My social life included weekends at Kampala’s most popular colonial-style country club, Kabira, and expat parties that stretched into the wee hours of the morning, reminding me of that infamous novel of colonial decadence in Africa, White Mischief. In the expat community, even the Peace Corps volunteers who spent their weeks covered in dirt from the work in their villages went to Kabira when they arrived in town for the weekend.

Kabira was breezy and inviting, with comfortable plush chairs, a restaurant shaded by tall, dark green trees, and a sparkling sky-blue pool. Inside, our flip-flops squeaked on the red tile floors as we alternated between our poolside lounge chairs and the bar. Ugandan waiters in crisp white-collared shirts and black tuxedo vests approached our chairs and asked if we needed anything. Families with small children splashed around in the pool, and groups of young expats in swim trunks and bikinis sunbathed and drank cocktails under the fading golden sun. My friends — including a goofy fellow from Texas and a slew of witty British citizens — and I joked about the previous night’s exploits.

I couldn’t help but feel uncomfortable and guilty when the Ugandan wait staff peered questioningly at me, wondering what I was doing there — the only black person in the group. At the time, I assumed they were harshly judging my leisurely lifestyle, but they probably were just curious.

I’d go out to local hangouts with my Ugandan friends without so much as a second glance, bargaining in the markets and walking the streets at night unnoticed — moments that I relished. I passed for a Ugandan so well that some expats ran their eyes over me disinterestedly when we first met, until I opened my mouth to reveal my American accent.

My skin color gave me benefits my fellow expatriates envied.

“You’re so lucky, you never have to worry about boda (motorbike taxi) drivers ripping you off, since they think you’re a Ugandan!” friends told me again and again.

At the same time, my passport gave me an advantage my Ugandan friends craved.

“Marry me and take me back to America with you,” male co-workers teased.

I wanted a less complicated existence. It could be overwhelming and lonely — a sense of being both native and foreign in Africa. I felt the joys and frustrations of being an American in Africa, and I also felt an unexpected, comforting kinship to Africans. But I never felt like I fit in with either group. I decided to stop trying to blend in and instead to appreciate my differences and accept both groups for who they were.

No responses yet