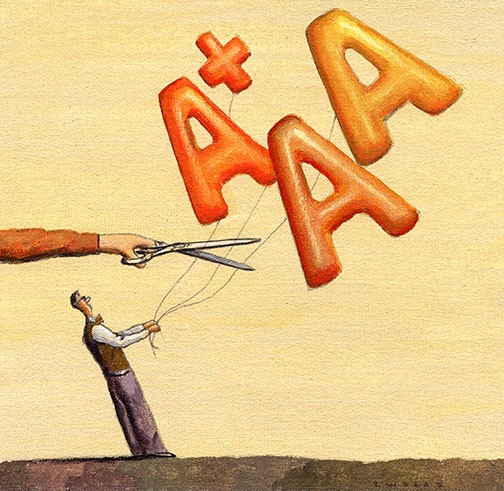

Fresh Look at Grading

Eisgruber raises grade-deflation questions, asks faculty members to review policy

Just four months into his presidency, President Eisgruber ’83 has launched a re-examination of one of his predecessor’s most controversial policies: curbing grade inflation.

A new faculty committee will review the University’s grading policies and examine several factors, including whether they have affected students’ employment prospects and graduate-school admission, Eisgruber announced Oct. 7. The move comes almost 10 years after the faculty adopted a goal of having A’s make up 35 percent of the grades in each department. A recent progress report found that goal hasn’t quite been achieved: In 2010–13, 41.8 percent of grades in undergraduate courses were A’s. That’s down from 47 percent in 2001–04 but higher than last year’s report, which showed that in 2009–12, A’s made up 40.9 percent of all grades.

The grading policy is an issue that Princetonians frequently raise when they interact with him, Eisgruber told PAW. “One of the things that worries me about it is that there is so much talk about the policy that it seems at times to be a kind of defining characteristic for the institution.” He added, “I say that as somebody who sympathizes with the objectives of the grading policy and voted for it and has long defended it.”

But it’s important, after 10 years, to re-examine whether the objectives set out by the original policy — providing fairness across departments and meaningful feedback to students — still are appropriate, and whether the policy is the best way of achieving them, he said.

At a recent forum with alumni in New York City, Eisgruber said that Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye had told him she was concerned that the policy may be discouraging students from coming to Princeton. “If we are inadvertently producing a kind of a side effect that can be avoided, that’s something to worry about, but I don’t think that’s the ground on which the committee should make its decision,” he told PAW.

Current students have expressed fear about losing out on jobs and internships because of the lower grades resulting from the policy, said Shawon Jackson ’15, president of the Undergraduate Student Government. Another gripe is that what constitutes an A “is contingent upon how other students do in the class by the end of the course,” so expectations of what level of work will earn an A are not clear from the beginning, he said.

Dean of the College Valerie Smith said the policy may limit employment prospects for some students in management consulting and finance. “I have certainly heard anecdotally that where our students may be disadvantaged is in certain sectors” where some firms have a GPA cutoff, she said.

No peer institutions have followed Princeton’s lead on grade deflation, though a Yale faculty committee in the spring recommended switching from letter grades to a 100-point scale and establishing non-mandatory grade-distribution guidelines.

A recent study found that students with higher GPAs were more likely to be admitted to business schools, even when those higher grades were attributable to more lenient grading. Don Moore, a co-author of the study who teaches at the University of California-Berkeley, said one part of the study used fictional transcripts submitted to 23 professional admission officers (another part of the research incorporated real admission data from four MBA programs). The transcripts from schools with tougher grading came with information about the school’s rigorous grading policy, a practice that Princeton also employs. “People have a hard time correcting the impression grades make,” Moore said.

Some faculty members “feel that the policy constrains them to grade in ways other than they would prefer to grade, and [there are] other faculty who I think fully support the policy,” Eisgruber said.

There are no students on the review committee — it is made up of nine faculty members — but their input will be sought. “I think it’s very important that the committee listen to students,” Eisgruber said.

English professor Jeff Nunokawa, for one, supports the re-examination of the policy. “The health of any institution depends on rigorous and periodic review of what it does,” he said. The review demonstrates, he added, that “very little around here is sacrosanct.”

1 Response

Emil M. Friedman *73

10 Years AgoA's Should Be Tough to Get

The article “A Fresh Look at Grading” (On the Campus, Nov. 13) discusses lowering the percentage of A’s to 35 percent. How can an A mean anything if it’s so easy to get? When I was an undergraduate at MIT (’64 to ’68), an A meant “outstanding by comparison to one’s peers” because only 10 to 15 percent of the grades were A’s. Grades in the math/stats program at Case Western in the ’80s were scaled similarly. Prospective employers knew that and took the competition at our undergraduate institution into account. Graduate schools knew that and also looked at our GRE scores. If A’s are so easy to get, prospective employers and graduate schools with any sense will also take that into account.