Cartoonist Charles M. Schulz did not set out to make the kids cute when he created Peanuts. In fact, Schulz wasn’t particularly fond of children, with the exception of his own. But comic strips featuring kids were popular when he was breaking into the business, so Schulz drew kids — voicing the wry humor and philosophical musings of his own inner child.

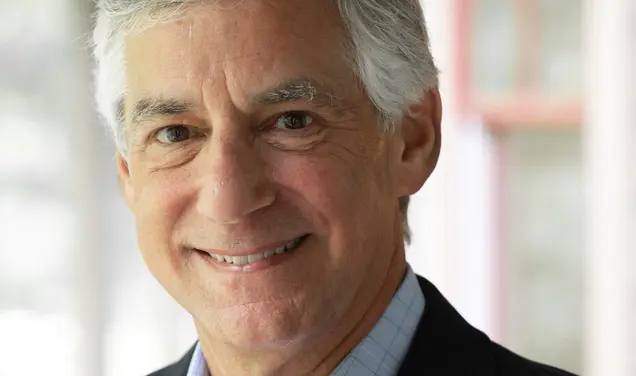

The birth of Peanuts, and how deeply it reflected the psyche of its creator, is the subject of a new book by David Michaelis ’79, Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, published by HarperCollins in October. Schulz spent 50 years drawing for newspaper funny pages; when he died in 2000, Peanuts appeared in more than 2,600 newspapers in 75 countries.

Michaelis, who grew up reading Peanuts, goes to great lengths to connect the dots with Schulz’s experiences, the characters he created, and the punch lines he wrote.

From the slow demise of Schulz’s mother from cancer and his romantic rejections to the high points of his Army days and his dogged effort to make it in comics, Schulz distilled his experiences into the comic strip panels, as examples interspersed throughout the book illustrate.

When his first wife, Joyce, began revamping the Schulzes’ California property, Lucy imagines Charlie Brown becoming president — so she can redecorate the White House. The beginnings of Charles Schulz’s extramarital affair found Snoopy writing adoring love letters, closing with a crazed smile (“Dear Sweetie, Have you missed me? I think about you all the time. I can hardly wait until Sunday morning. Don’t forget ... I think I’m in love!”).

According to Michaelis, who conducted more than 200 interviews, Schulz was both self-doubting and determined, melancholy and charming, decent and caring, yet prone to blame others for situations that didn’t go his way. Interviewers asked if he was Charlie Brown so often that Schulz told them what they wanted to hear and shaped his version of his life story accordingly. “Peanuts was his life, his work, his identity, his yin and his yang,” says Michaelis, author of a prize-winning biography of illustrator N.C. Wyeth.

While Michaelis found much to admire, he also was stunned at how his subject resisted looking analytically at his life. In tapes of an unfinished interview that Michaelis discovered during his research, Schulz “bobbed and weaved” in response to questions. For example, when Schulz stated that he had felt alone all his life, the interviewer pressed him to explain how that was possible for a man with five children. “I was surprised that someone this complex hadn’t really looked deeper into his life,” Michaelis says. “He gave it all to the comic strip.”

In an Oct. 8 New York Times article, members of Schulz’s family who were interviewed by Michaelis for the book took issue with Michaelis’ portrayal of Schulz, which they felt showed him as a depressed, cold, and bitter man. They said that Schulz was much happier than he comes across in the text. Michaelis defended his work, telling Patricia Cohen *86 of the Times, “This was the man I found.”

Michaelis writes for numerous magazines, has penned a novel, and perhaps most famously in Princeton annals, co-authored Mushroom, a headline-maker based on roommate John Aristotle Phillips ’78’s junior paper on how to construct an atomic bomb. But his career really blossomed with the Wyeth book — which, coincidentally, Schulz was reading when he died.

No responses yet