Goldberg Family Collaborates on Latest Installment of Inspector Mazarelle Series

The book: The latest installment in the acclaimed Inspector Mazarelle series, The Hanged Man’s Tale (Doubleday/Nan A. Talese) chronicles the return of Paris’ most brusquely charming detective, Paul Mazarelle, this time on a murder case. A tarot card is the only lead at the crime scene. While Mazarelle hotly pursues the killer, journalist Claire Girard, enmeshes herself in the same story as well — leading Mazarelle to face decisions he’s never had to make before. The investigation takes a number of twists and turns through the underbelly of the city filled with corrupt cops, white supremacists, and other unsavory characters. Like the first in the series, this thriller will have you on the edge of your seat.

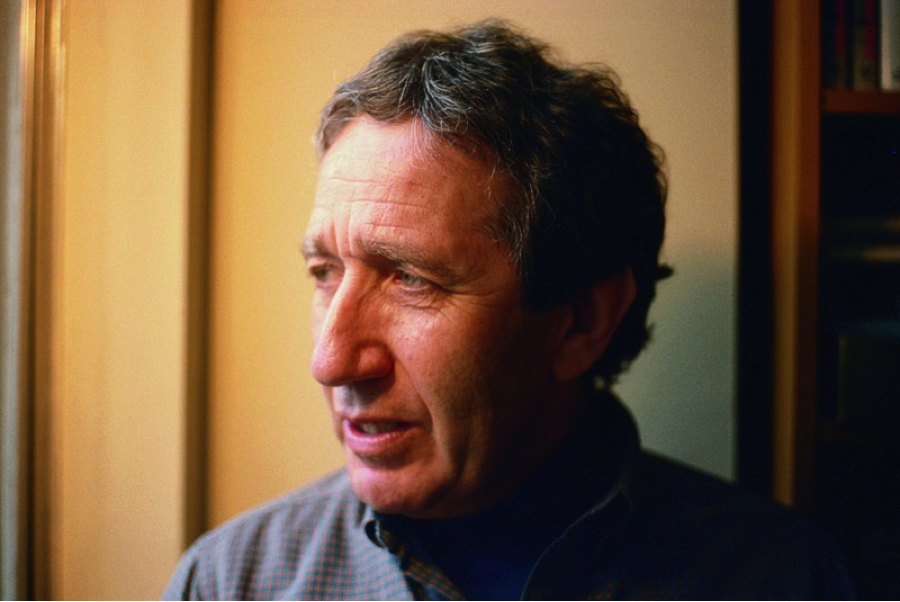

The authors: Gerald Jay Goldberg, writing under the pen name Gerald Jay, was the author of nine books, including the first book in the Inspector Mazarelle series. After he began working on the second book, The Hanged Man’s Tale, Goldberg fell ill and died in June 2020. This novel was completed in collaboration with Goldberg’s family, Robert Goldberg ’79, James Goldberg, and Nancy Marmer.

Excerpt

Prologue

He told close friends about his plans. No one believed him. “Watch the TV this Sunday,” he said. “I’m going to be a star.” Of course they didn’t take him seriously. But that’s the way they were, his few close friends. No dreams bigger than banging a Deshi on the Métro or blowing up a kosher deli in the Fourth. To the rest he e-mailed, “Death to Zog (88).” Then he glanced at the calendar on his bedroom wall where the fourteenth of the month was circled in red. Only one more day. His alarm clock on top of the bureau was set for 5 a.m. At that hour on a Sunday there shouldn’t be any bottlenecks, but tomorrow was a national holiday. And driving to the center of Paris was never a picnic at any hour. His clothes were already laid out and ready to go, neat as a pin. Like Mishima, military style. The tan chinos, a crisp blue shirt, his black windbreaker with its black hood. Naked he climbed into bed, pulled the sheet over his head, closed his eyes. Dead quiet outside. Known by the locals as wild doings in Courcouronnes, or family high life in the burbs. At least it was good to have the two of them out of the way, the house all to himself. Not to mention the old boy’s big Gibson left behind. And tomorrow—he rolled over, pounding his pillow—was another day.

In the still black room the next morning, the red alarm went off like a dynamite vest. Five on the digital dot. Picking up his sheet from the floor, he tossed it back on the bed. He had urgent plans to attend to—a marquee future featuring his name in lights. One outstanding success that would redeem a life full of petty failures. Shaved, showered, dressed, and well caffeinated, with two cups of coffee to the good, he quick-marched across the room to check himself out in the mirror. “Ready for your close-up, Max?” Max smiled. “Okay! Roll ’em!” He picked up the brown guitar case with its Gibson USA label, slammed his bedroom door closed, and strode out the front entrance into the cool gray dawn. The big case went into the trunk of his car. Before climbing in, he glanced back at the neat row of two-story buildings. They called their house the white pavilion. He called it their bourgeois dream—a bland, vanilla shoebox. Edging the property, a strip of dark green shrubs. The last thing she said before leaving on vacation was one final castrating order, “Remember, Max. This time don’t forget. Water the plants or they’ll die.” He’d forgotten, of course, but it made no difference. As a parting gesture, he unzipped his fly and peed all over her hedge. It looked refreshed. The damn thing flourished no matter what he did. Or didn’t.

Once in Paris, everything went like clockwork. He left his car on a side street near the Parc Monceau and, case in hand, walked toward the starting point of the parade on the Champs-Élysées. Less than a stone’s throw from the flag-draped Arc de Triomphe. That was the direction from which the president would make his initial appearance. Max stood behind the low metal police barricade, patiently waiting with the rest of the early birds. He could see everything from there. A perfect position.

Commandant Paul Mazarelle had always enjoyed the Bastille Day parade. The sappers of the French Foreign Legion with their orange leather aprons and shouldered axes. The caped Spahis. The glittering casque-d’or cavalry of the Republican Guard. And in the sky above Paris, the blue, white, and red smoke contrails of the roaring Patrouille de France Alpha Jets. But this year he didn’t think he’d have time to savor the color.

They were expecting a large crowd—perhaps one hundred thousand or more. Only two months ago President Chirac had been reelected by a landslide in a contentious runoff with the ultra-rightwing Jean-Marie Le Pen. Parisians, by and large, were glad. They didn’t care for extremists. This year they cared for Americans. Ten months earlier al Qaeda terrorists had destroyed New York’s Twin Towers. Today, the theme of the Bastille Day 2002 parade was Franco-American friendship. Among the honored guests in the parade reviewing stand on the Place de la Concorde were members of the FDNY. And as a special honor on the two hundredth anniversary of France’s military academy, a trim contingent of West Point cadets—white summer pants, gray fitted jackets—had been invited to march beside the flamboyant young Frenchmen from the SaintCyr, their red and snowy white plumes fluttering.

In spite of all the frills, parade duty was no one’s idea of a good time. For Mazarelle, it was a not-so-subtle hint. He might be a commandant in the elite Brigade Criminelle, but his new boss was reminding him that, whatever famous success he’d had in the Dordogne, he wasn’t above crowd control in Paris. Four decades after Maigret, no one liked a celebrity detective. Knocking on the door of the large white PC Police van, Mazarelle pushed it open and tried to step inside, but there was little room for a man his size. The intelligence unit—officers seated in shirtsleeves before their computers, telephones, LED maps, closed-circuit TV screens, shortwave radios, and other electronic gear—was a humming beehive of activity. One of the officers glancing up recognized him. “Can I help you, chief?” “You’re busy. I’ll come back.” “Just a minute.” She brushed her blond hair back, picked up her pack of Gauloises, and came out to join him. “I was going for a smoke myself. Have one.”

“Sure.” Mazarelle liked the steady way she cupped her hands around the offered match. He took a deep drag. Ech! It reminded him why he’d given up cigarettes. He’d been so busy that morning when he left his office he’d forgotten to take his pipe. “Thanks,” he said, and inhaling once again coughed up the smoke. She smiled, seemed glad to see him. He didn’t know why. They had barely exchanged more than a word or two at the 36 Quai des Orfèvres party. “So you only visit on holidays?” Her eyes sparkled as she tucked her hair behind her ear. On the inside, Mazarelle was sparkling too. When a woman ran her fingers through her hair, four decades of experience told him it meant one thing. He’d forgotten what her name was, but he’d find out. She was a woman who wore a Beretta on her hip as if she knew how to use it. Definitely worth keeping an eye on. And probably the right person to ask about threat levels and security. She nodded. “Raised to twenty-five hundred policiers and gendarmes as well as the elite units GIGM and RAID. Plus air force reconnaissance planes and fighters above the parade route.” She patted him on the arm. “Feel safer?” “Sounds good—” he started, interrupted by a sudden burst of Lester Young’s creamy tenor sax. “Excuse me.” Mazarelle pulled out his mobile, listened for several seconds. It was a member of his team at the Étoile with a heads-up. The parade was about to start. Mazarelle replied in a muted conspiratorial voice that he was on his way. “Sorry,” he turned to apologize, but she was gone.

He found his young aide, Lieutenant Jean Villepin, not far from the Étoile. Plainclothes Jeannot had a rocker’s scalp full of long, stringy, dirty-blond hair. He wore a scruffy blue sweatshirt, grimy Nikes, and torn jeans to go with it. Mazarelle asked, “Where’s your police armband?” “In my office.” “Looking the way you do, you’ll need it. Here, take mine. The Champs-Élysées is getting jammed. But we’ve got a few of our men sprinkled among all the others along the route from the Arc de Triomphe to the reviewing stand at Concorde. Now get over to the rue Washington. When the president goes by, I want you shadowing the car all the way down the avenue.” “I’ll handle it,” Jeannot assured him. “Above all, no matter what happens don’t let him out of your sight. Can you do that?” “I think so.” “Good. We’ve got the counter-sniper teams up above. But we need more bodies on the street. Besides, you’ve got the legs. I’ve seen you take the stairs three at a time at 36.” Mazarelle pointed to his beat-up Nikes and winked. “Just do it.”

Max heard the band in the distance. Then, coming out from behind the Arc de Triomphe as if a cloud had lifted and the sun appeared, the open-topped presidential jeep sporting small elegant French flags fluttering front and rear. The jeep moved slowly, decorously along the Champs-Élysées, preceded by a rolling wave of cheers, whistles, laughter, applause. And there he was at last! Reelected for five more years rather than seven, but five too many as far as Max was concerned. The president of France himself standing in the open jeep behind his uniformed drivers like a fuckin’ god in his gleaming chariot, smiling and waving to his adoring subjects.

Max felt that he could practically touch the president as his jeep approached. How could he miss? Pulling his rifle out of the case, he snapped it up to his shoulder. “Time to die, monsieur le président!” Max cried. Taking careful aim, he fired. The noise of the crowd and the music of the parade were so loud few heard the shot or knew where it had come from. Those nearby who knew screamed for the police. Mazarelle could hear from the alarm in their voices that it was serious and saw at once where they were. For a big man with a limp, he moved through the crowd with astonishing speed. Before the gunman could get off another shot, the commandant had pounced on him, tearing the rifle out of his hands. It looked like a .22. A funny low-caliber hunting gun all wrong for a serious assassin.

Other cops soon surrounded them. Captain Maurice Kalou of his homicide team materialized at his side to log the rifle for evidence. Jeannot, down on his hands and knees, had already scooped up a shell casing. By now, two uniformed policemen had the prisoner’s hands pinned behind his back and clamped in handcuffs. They each grabbed him by an arm and dragged him to the waiting van with its side door open. “Wait a minute.” Mazarelle covered the prisoner’s head with his hood. “That’s better. Watch his skull,” he warned them. “We don’t want him to get hurt.” They shoved him into the van and slammed the door. As the hooded Max sat in the dark, alone with his crazy jumbled thoughts and the people outside howling for his head, the police van raced off to the Quai des Orfèvres, siren wailing.

Reviews

“Gerald Jay is truly a master... a bright star in the world of crime fiction.” —Mystery Tribune

“What Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther is to Berlin, Gerald Jay’s Paul Mazarelle is to Paris: the world-weary cop condemned to figuring out which of his colleagues is the least trustworthy. Cinematic and suspenseful, laced with sudden turns, The Hanged Man’s Tale is a gripping read -- a classic roman policier set in the thoroughly modern streets of Paris. You can taste the espresso in the cafes, and feel the danger lurking in the shadows.” — Alexander Wolff, author of Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape, and Home

No responses yet