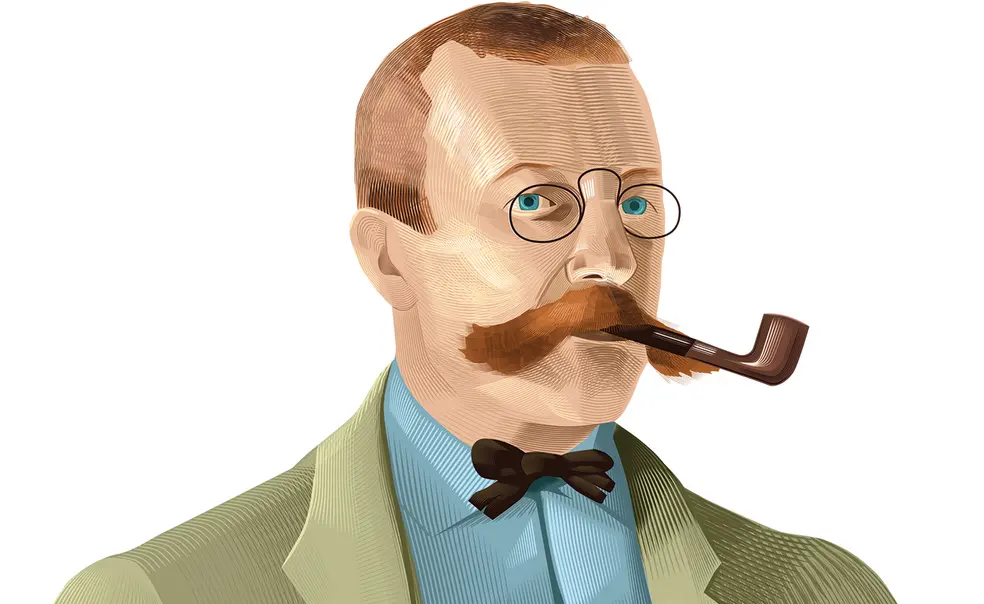

Before Laurence Hutton h*1897 started collecting heads, he established himself as a prominent man of literature. The son of a wealthy merchant, he grew up in New York City, where he skipped college in favor of touring literary Europe and then joining the scribbling game himself. He worked as a theater critic for the New York Evening Mail, then a literary editor for Harper’s Magazine.

In 1897, Princeton awarded Hutton an honorary degree of master of arts. He had already been thus honored by an institution in New Haven, but he understood which honor was greater. He moved to Princeton, where he lived with his family at the Princeton Inn and made frequent use of the University’s library. Whenever in New York City, he socialized at the Princeton Club. From 1901 onward, he worked as an instructor in Princeton’s Department of English.

Soon after he became a Princeton man, Hutton presented to the University a collection of 74 death masks. “I thought I’d like to do something for the University,” he said. “So far as I have been able to discover, mine is the most nearly complete and the largest collection of its kind in the world.”

The collection was ostensibly scientific: For centuries, men of learning, believing the workings of the brain must shape the head, had sought to learn the secrets of greatness by taking plaster casts of the heads of great thinkers — by any means necessary. (This pseudoscience, known as phrenology, contributed to racist theories, especially about Black people.) Thus it was for the masks in his collection. They represent the astonishing lengths men went to in the quest to capture those valuable faces: digging up bodies; stealing impressions from the coroner’s table; haunting the curiosity shop, the dissecting room, and the charnel house.

For example, a mask of Shakespeare in the collection was said to be an impression taken from a death mask that a friend secretly made of the playwright before his burial. A mask of William Makepeace Thackeray, likewise, was made by a friend of the author after his death. Thackeray’s family asked that it be destroyed, but the friend refused.

The body of France’s Henry IV was exhumed from his grave during the French Revolution; Parisians lined up to see the old monarch’s face, and one of them supposedly made his mask. Robespierre, by contrast, had his head preserved for posterity before he even went to the guillotine; by prior arrangement, the revolutionary government sent it to Madame Tussaud so that she could add his likeness to her waxworks.

As a literary man, Hutton recognized the face of the author Laurence Sterne when he saw his mask in a curiosity shop, though no such mask was supposed to exist. He bought the mask and investigated its origin. According to the story he pieced together, after Sterne’s burial in a London churchyard, “resurrection men” dug up his body, not knowing it belonged to someone famous, and sold it to a medical school. A doctor who knew Sterne recognized with horror the face of his friend. He reclaimed the body and buried it properly — and, along the way, made a death mask.

Hutton took great pleasure in describing the gory origins of his collection.

“I am sure that mine is the actual death-mask of Aaron Burr [1772],” he wrote, “because I have the personal guarantee of the man who made the mold in 1836. I am positive of the identity of another cast, because I saw it made myself. And concerning still another, I have no question, because I know the man who stole it!”

Today, we no longer think of this messy business as scientific, although we continue to search for meaning in artifacts like Percy Shelley’s heart and Ezra Pound’s teeth, as well as the very physical historical remains that are books, diaries, letters, drawings. What are the humanities but resurrecting the dead?

There is no death mask of Hutton in his own collection. But he’s buried, very conveniently, in Princeton Cemetery, if an alum wants to obtain one for the library in the old-fashioned way.

3 Responses

Jim Merritt ’66

1 Year AgoHutton’s Masks on Display

I enjoyed Elyse Graham ’07’s Princeton Portrait of Laurence Hutton and his death mask collection in PAW’s October issue. For years, a sampling of these masks was displayed in vitrines in the now long-gone Rockey Room on B Floor of Firestone Library. The Rockey Room housed the angling book collection of Kenneth H. Rockey 1916 and included a sitting area with comfortable padded chairs, like a gentlemen club’s lounge. I visited it frequently in the 1980s because of my interest in fishing, but the masks had their own lurid appeal. Somewhat less appealing was the perpetual eye-stinging pall — and stench — of cigarette smoke. The Rockey Room was the last remaining space in Firestone that allowed smoking. Arrayed under glass, the masks were a grim memento mori presumably lost on the smokers who gathered there.

Editor’s note: The author, PAW’s editor from 1989 to ’99, recommends Wes Tooke ’98’s 1998 story on the Hutton collection, “Immortality in Plaster,” available online here.

Jay Geller ’95

1 Year AgoAnother Hutton Legacy at Princeton

In your biographical sketch of Laurence Hutton — honorary degree recipient, instructor in the Department of English, and donor of a collection of death masks — you omitted one other notable connection to Princeton. He is the namesake of the Department of History’s top prize, which resulted from a donation in Hutton’s memory in 1914 by his friend Samuel Elliott, a publisher and rare book collector in New York.

Steven M. Brown ’77

1 Year AgoMemories of the Mask Collection

I really appreciate this article. I’m not exactly sure how, but my student employment at Firestone Library in the mid-1970s (probably for about $5 an hour) led to my participation in the cataloging and archiving of these masks. I still remember the eerie and honored feeling of holding Abraham Lincoln’s mask in my hands.

Thanks for confirming that this slightly macabre memory was not simply a dream.