The Hiss Hassle Revisited

From the PAW Archives, May 1976: When Whig-Clio invited Alger Hiss to Princeton, the issue wasn’t free speech but students’ rights

Princeton never heard a louder uproar than when its “silent generation” joined in a protracted and very public two-step with Alger Hiss in 1956. The pairing of Princeton and Hiss, two powerful symbols capable of arousing deep and opposite feelings, put the university to an extreme and unwanted test. Yet looking back at the “Hiss Hassle” from the vantage point of today’s open campus and iron-clad freedom of speech, many people—including some of those who were involved then—can’t fathom “what all the fuss was about.” Others now regard the incident as an early triumph of free speech, or even as a defiant slap at the bugbear of McCarthyism. A careful review of what actually occurred, however, reveals that at the time these were peripheral concerns and at most indirect results of the affair.

All the fuss turns out to have been about matters more complex than free speech and more human than witch-hunting. To understand them, we must recall the attitudes, pressures, and values which lay at the heart of a younger Princeton, and another America. In the mid-1950s, the mood of the university, like that of the nation, was expansive. Princeton was coming off a wave of post-war confidence generated by a proud World War II record, a festive bicentennial celebration of its founding, the building of a new library, gymnasium, and school of international affairs, the expansion of its academic program, six Big Three football championships in a row, and an unprecedented $1 million in Annual Giving.

Harold W. Dodds *14, the 66-year-old dean of American college presidents, was nearing the end of a popular tenure that had spanned three decades. The college of 2,900 men was personal, cohesive, and noted for its conservatism. Undergraduates had just packed Alexander Hall to hear Billy Graham, and Grace Kelly was being spirited off the screen of the Garden Theater for the principality of Monaco.

“We were full of the feeling that comes with power and the feeling that comes with success,” says Donald Griffin ’23, then secretary of the Graduate Council (later the Alumni Council). “No period like this can last forever. The bubble burst with Alger Hiss.”

When the bulletin came across the six o’clock news announcing that Hiss would speak at Princeton April 26 on “The Meaning of Geneva” at the invitation of the Whig-Cliosophic Society, President Dodds and his administrative chiefs were aboard the steamboat Delta Queen on the Ohio for an evening celebration of the National Alumni Association. Cutting short their stay with alumni leaders in Cincinnati, the administrators boarded a Princeton-bound train on Sunday, April 8, and braced themselves for what the president later termed “a grievous three weeks.” Dean of the College Jeremiah S. Finch said, “Everyone assumed that this would be trouble. We just didn’t know how much.”

Although the news had taken the men by surprise, it was not a complete bolt out of the blue. In fact, they had been wrangling with Whig-Clio over the invitation since mid-March, and had left the matter hanging (they thought) when they departed for the Cincinnati conference. The dispute had begun simply enough. In an attempt to boost sagging attendance after a year of relative stagnation, the Halls’ new officers in early March sent speaking invitations to 19 political figures who would be as varied and controversial as possible. The list included Vice President Nixon, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles ’08, generals Marshall and MacArthur, senators Sparkman and McCarthy, John L. Lewis, and Hiss. The idea to ask Hiss came during a late-night bull session of the society’s executive committee, including President Bruce Bringgold ’57, Vice President John Stennis Jr. ’57 (son of the Mississippi senator), Stennis’s roommate Lister Hill ’57 (son of the Alabama senator), and the Halls’ Secretary, Virginian William Pusey ’58. (At the height of the controversy, when student loyalties were being questioned, one wag remarked, “Whig-Clio is the only ‘communist’ organization on earth run by people who favor segregation on the buses.”) Hiss’s name was brought up because someone at the meeting remembered reading that he had been asked to speak before the Swarthmore College chapter of Americans for Democratic Action. (The national ADA, however, had rescinded the invitation on grounds that Hiss was a “convicted traitor.”)

Hiss, finishing parole after his conditional release from Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in December 1954, quickly accepted Whig-Clio’s offer and picked the April 26 date. Much later he noted that he was grateful to the society’s officers for giving him “the initial opportunity to break out of Coventry.” The Princeton speech would be his first public appearance since he was tried and convicted five years earlier on perjury charges for denying he had passed on secret documents for transmission to the Soviet Union while a high Washington official. The famous “pumpkin papers case” had played across the nation’s front pages for two-and-a-half years, exciting fierce and blinding passions on all sides. Widely viewed as an embodiment of the establishment ideal, Hiss seemed to the public, in historian Eric Goldman’s words, “morally and in common sense [to have been] indicted for spying against the United States in behalf of the Soviet Union.”

There was soon to be much speculation about Whig-Clio’s motives in bringing Hiss to the campus. While many critics believed that the officers selected him out of a youthful desire to create a sensation and draw a crowd, Stennis maintains that “it was not a grandstand thing.” New York Times political correspondent R.W. Apple ’57, who was then chairman of The Daily Princetonian and closely involved in the affair, explains, “We were a little young to be as sensitive as we might have been inviting Hiss.” Others doubt that the students were as naive as they professed to be.

Ironically, another student group—headed by Ralph Schoenman ’57, a “firebrand radical” who went on to become secretary of Bertrand Russell’s anti-bomb campaign—had tried to draw Hiss a year earlier. Politics professor Hubert H. Wilson, who was controversial for defending the rights of accused Communists, remembers stepping in to kill Schoenman’s bid, which he felt was “motivated by a desire to embarrass the university and embroil it in tremendous controversy. After all that, it amused me that the most respectable organization on campus invites him a year later!”

Whig-Clio did not notify the administration of the invitation until after Hiss had accepted it, thus ignoring the prior-consultation understanding by which speaking invitations were to be discussed with administrators before they were issued. This “standing procedure” played a consultative, not a censorship, role and was intended for administrators to advise students on the larger context and ramifications of their actions. But there seems to have been some confusion at the time about this “gentleman’s agreement,” which Professor Samuel C. Howell, chairman of the Whig-Clio trustees and administrative-faculty liaison with the Halls officers, said was based on “the understanding that student conduct would be unobjectionable.” The Whig-Clio officers claimed they had never heard of the prior-discussion agreement, and later had it altered in writing. “They did a little end run,” as Finch put it. Normally, the officers would also consult Howell on such a speaker. “In this case, they stayed carefully away from Sam,” Finch noted.

After Dean of Students William D’O. Lippincott ’41 was informed of Hiss’s acceptance, he brought the matter before the President’s Administrative Council (composed of the deans and chief administrative officers of the university), where it was debated at length. Rejecting a proposal to intervene in the affair, the council decided that “the serious implications of the invitation should be made emphatically clear to the undergraduates” but that the students should be left with responsibility for their action. This meant that the administration would not order students to rescind the invitation, but would spare no effort to persuade them to do so. Once the council made its decision, it was the students’ wisdom in inviting Hiss, not their right to do so, that was at issue.

On Thursday, March 22, Finch and Lippincott held the first of several meetings with Bringgold and Stennis, at which were stressed the “full scope and serious implications” of their action and its probable impact on public opinion. No instruction or threat to rescind was ever made during any of these sessions by either the Whig-Clio trustees or university administrators. “We were all students of John Stuart Mill,” says Howell, “and this was no more than putting to use the Millian conception of free vs. coerced consent.” Stennis praises Howell’s wisdom and patience, and says, “If you grant the reasonableness of their assumptions, and I do, then their pressure was proper.”

There is much to indicate that the administration, and most of all President Dodds, was going deeply against the grain in allowing the student invitation to stand. “Dodds sincerely felt that the appearance would jeopardize the status of the university,” Stennis recollects. “He was suspicious of Hiss’s intentions.” University officials were concerned that Hiss was using Princeton’s prestige to launch his rehabilitation effort: “I can see what Hiss gains from Princeton, but what does Princeton gain from Hiss?” wrote one official.

The Halls officers conferred among themselves and then met again with administrators before leaving for spring vacation. Dean Lippincott reiterated Nassau Hall’s concern and tried to talk the students into canceling Hiss. “The issue was how it would look from a PR standpoint to have a convicted perjurer speak under the auspices of a long-standing student organization,” he recalls. By Easter break, Lippincott felt the officers would rescind the invitation. When they returned, however, Bringgold let it be known that the program would go ahead as planned. This brought on more meetings, during which Bringgold held firm, but the administration left for its long weekend in Cincinnati on April 4 feeling that the matter was still up in the air.

The next morning, the Princetonian broke the story that Whig-Clio would bring Hiss to campus to “relate the meaning of last summer’s summit conference at Geneva and the implications to the Yalta conference,” at which he had been an adviser to President Roosevelt. Whig-Clio said that “although Hiss’s record is not condoned,” his experience and opinions would be “of interest and value to Princeton undergraduates.” The University Press Club picked up the story, and by the following day it was making headlines across the country, setting into motion what Dean Finch called “a long trip across the swamp.”

“The news went like lightning via the Princeton grapevine, which is probably even faster than the wire services,” says a class officer. After hurrying back from Cincinnati, an apprehensive administration was greeted Monday by the first trickle of protesting telegrams and calls. That day the Hearst chain (including the New York World-Telegram) ran an editorial hitting Whig-Clio for “a corny show-off, pure and simple . . . it wasn’t long ago that some Princetonians were gaining notoriety by swallowing goldfish. They now think they can get more of it by swallowing Alger Hiss.” Angry and abusive messages also reached Halls officers, but merely served to strengthen their resolve to go ahead.

Media interest, particularly in New York and Philadelphia, was stimulated by reports of alumni displeasure at the Princeton Clubs in those cities. Pressed for a statement of his position, President Dodds told reporters Monday afternoon that Whig-Clio had invited Hiss “on its own initiative,” and that while the administration had “some weeks ago warned the officers of the society of the implications of an invitation to a convicted perjurer, we think it unwise now to take responsibility for the decision out of the hands of the student organization.” Bringgold flatly stated that he would not consider rescinding the invitation. Overall, criticism was termed “very slight,” and officials planned to play events day by day and as low-key as possible, expecting some trouble but not a storm.

Headlines the next day were “Hiss Criticism Slight; Unwise to Overrule Bid, Princeton Prexy Says.” Administrative Secretary Edgar M. Gemmell ’34, Dodds’s right-hand man during the affair, recalls his own “fatal error”: “The factor militating against the speech’s ever coming off was the long lead-time—it gave the opposition a chance to mobilize. So when the Press Club guy called to ask how the reaction was running, like an idiot S.O.B. I told him, ‘Oh, very slight, really.’ Within 36 hours the postman was absolutely bowlegged bringing in the sacks.”

The trickle of protest swelled to a stream on Tuesday, when U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Livingston Merchant ’26, ambassador-designate to Canada, and later a Princeton trustee, made public his telegram to Bringgold strongly urging the speech’s cancellation. Merchant said he was “deeply disturbed” at the news and “cannot believe that Hiss’s ‘views would be of general interest to the faculty and student body.’ ” The appearance would do “lasting and irreparable damage to Princeton,” the diplomat declared. (The New York Daily News headlined, “One Hiss Could Start Tiger Roar, Ex-Tiger Says.”)

By Wednesday, the stream was becoming a deluge, and university officials were publicly admitting their alarm over the volume and vehemence of alumni and outside criticism. “We were astounded,” one administrator recalls. Gemmell, who was responsible for public relations, expressed concern not so much with the number of objections as with “the profound disturbance they portrayed in the hearts of so many thoughtful friends of Princeton.” The final count would total more than 4,000 communications, about 40 percent from alumni and the rest from non-Princetonians. About 15 percent of the responses were characterized as obscene or abusive, 15-20 percent as supportive, and 65-70 percent as rationally opposed. Among alumni the reaction was 3-1 opposed; the non-Princetonian group ran 5-1. These figures do not take into account the heavy volume received by Whig-Clio and alumni class officers.

On the campus, however, an informal Prince poll showed 88 percent of the undergraduates and 95 percent of the faculty in favor of Hiss’s appearance, supported by 62 percent of the townspeople. A local press poll had 90 percent of the students and 45 percent of the townspeople favoring the visit. Respondents were personally unsympathetic to Hiss, and a few said the principle of free speech was at stake. One student was quoted as replying, “Isn’t that the American way?” History professor Eric Goldman commented, “Undergraduates here, though conservative, are eager to prove that Princeton is genuinely free.”

But free speech was not generally perceived to be the issue, on campus or off. In fact, it clearly emerges from memoranda and interviews that had the invitation been faculty-related or directly sponsored by the university, rather than student-initiated, cancellation would have been swift. Moreover, controversial speakers were nothing new at Princeton. Celebrated socialist Norman Thomas ’05 often spoke to rapt audiences at the university during this period, and though many alumni did not approve of his ideas, they regarded him as a loyal Princetonian and voiced no appreciable protest. Similarly, Earl Browder, then secretary of the American Communist Party and a resident of Princeton, “used to give talks all the time on campus to yawns and boredom,” according to John D. Davies ’41, PAW’s editor at the time. “It was the association of Princeton and Alger Hiss that was the frightening thing, not what he’d say.”

Hiss himself did have ties to Princeton other than as a bringer of controversy. He had wanted to attend the university but could not for financial reasons, and many of his Baltimore friends attended Princeton while he studied at Johns Hopkins. He confesses an affection for Princeton and still remembers watching the 1928 P-rade, in which a law school classmate was marching. Hiss had friends among the faculty, and he later said of his 1956 visit, “I’d been to Princeton so often that I thought it would be the same.”

During the controversy, many people had the impression that Hiss was a Princeton man, and the resentment of common people toward “Dean Acheson Ivy League types” showed itself in outside comment about Princeton’s “taking back one of its own.” It was also noted that some of the other members of Hiss’s alleged 1930s Communist cell, the “Ware group,” were Princeton alumni. Despite the administration’s efforts to distance itself from the invitation, much of the public thought Princeton had sponsored the appearance or was even offering Hiss a lectureship.

Many of Princeton’s most devoted alumni and friends, who would never think of protesting the campus appearance of a radical speaker, were deeply troubled and angered by the situation. Dean Finch says, “We had a big pile of letters beginning, ‘I’ve never before written a letter of protest . . .’ and these would come from moderate, level-headed people. Their concern was not so much that Hiss was controversial, but that he was a convicted perjurer, and there they had a point.” David Lawrence ’10, publisher of U.S. News & World Report, argued privately with university officials that, by listening to Hiss, an outstanding group of students would in effect say they were willing to accept a convicted perjurer and implicit traitor as a competent witness. Lawrence suggested that Hiss speak on prison life, or ornithology (he was an avid bird-watcher, a fact that had helped link him to his accuser, Whittaker Chambers, in famous testimony eight years earlier).

The conflict was not long in reaching Washington, where it stirred agitated debate on the floor of Congress. “Thousands of Princeton alumni read with shame and disappointment about the invitation,” fumed South Dakota Senator Karl Mundt. “To invite a convicted agent of the Communist conspiracy to visit the campus and advise them on the meaning of Geneva hits an all-time low.” Mundt suggested a more appropriate theme for Hiss would be “the betrayal at Yalta,” and predicted that soon Lucky Luciano would be invited to lecture about narcotics. “If this is modern education or academic freedom, heaven help all of us.”

A heated exchange was set off in the House when Jersey City Representative T. James Tumulty exercised his inimitable oratory on the university, calling Whig-Clio officers “diaper Dans,” “comic-book Ciceros,” and “Katzenjammer commissar fans.” The incident “suggests there’s a little poison ivy creeping into the Ivy League,” he said, wondering if Princeton might “award a posthumous LL.D. to Benedict Arnold” or “go a step further and have a Department of Treachery, manned by Hiss himself.” Tumulty asserted that Hiss’s lecture would advance “the cause of atheistic communism,” and that “Old Nassau will be called Old Nausea.”

Several congressmen joined him in a round-robin attack until Democrat Frank Thompson (whose district included Princeton) defended the university’s right to invite “anyone they like, though I deplore this choice.” Alfred Sieminski ’34, also a Jersey City Democrat, suggested that Hiss should be barred from all campuses. “If Hiss does not like this form of government, he should be permitted to go to Russia or any other country that will have him.”

The congressional debate dragged on for several days, and there were calls for an investigation of the university’s action. New Jersey Senator H. Alexander Smith ’01 declared that Whig-Clio “has acted in a way to bring discredit and negative pub-licity on Princeton’s good name” and that undergraduates “should arrange for their talk privately, off the campus, and entirely unrelated to the university.” Congressman Tumulty publicly pressured New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner to intervene in his capacity as an ex officio member of Princeton’s Board of Trustees. Ultimately, Sieminski rose to defend the university for not bowing to the protest. He proclaimed that if the entire population were against one Princeton man “who believed he was right,” it “would not frighten that Princeton man, and he would not flinch.”

From the reaction that poured in during the first week, it did appear that nearly the entire population was against Princeton, but according to one aide, “It was the big alumni guns and prominent figures who really shook Dodds.” A student leader recalls, “The shadow of McCarthy was fairly long then, though discredited. Dodds was shaken by the McCarthy era and, as a lame-duck president, he wanted to protect the faculty from a possible investigation—some alumni hinted at this.”

If Princeton’s president did not flinch, insiders report that at times he did seem to be wavering. Dodds was personally repelled by Hiss’s record, as he made clear publicly and privately, and the decision to allow the visit was made no easier by the serious opposition of Dodds’s wife, Margaret. Participants say he was not so firm in his conviction that the event should go forward as were his younger assistants. “He had complete control of the situation, but he didn’t seem to know that,” notes one. In the many strategy sessions held at night in Prospect, then the president’s residence, his advisers would break out a bottle of “Wild Turkey” to ease the pressure, though Dodds was not a drinking man. It helped to “put strength in his arm,” one aide recalls.

During the day, all other university business came to a virtual standstill for the duration of the controversy, with constant meetings between Dodds, Howell, the deans, Whig-Clio officers, administrative officials, and some trustees. In the more familial atmosphere of that smaller Princeton, the administrators’ relations with student leaders were paternal, a far remove from later confrontation politics. The students were bluntly told that they had been “rash, stupid, and silly” to invite Hiss. Of Nassau Hall’s “boys will be boys” attitude, Stennis says, “It may be hard to appreciate after the Vietnam days, but it didn’t bother us—it was the approach of the Eisenhower era.” The Whig-Clio officers spent long hours with Dodds and other top officials, reading and discussing the letters and tele-grams, and hearing the administration’s concerns about the implications of the af-fair. The students, who had been only 12 to 14 years old when the Hiss case broke, were astonished at the gravity of the pro-test, and seriously reconsidered their position. For Stennis, it was a painful but unavoidable decision: “We loved those men too much, and Hiss didn’t mean that much to us.” Meanwhile, in the absence of any policy statement after the officers’ ex-tended sessions in Nassau Hall, and with the general knowledge that the administration was hoping for a discreet way out, rumors were spreading on campus that Whig-Clio would cancel the event. Then Bringgold headed home to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, for a long weekend.

The next morning, Thursday, April 12, the Princetonian ran a front-page editorial congratulating the administration for refusing to intervene, and declaring that the university’s reputation “will suffer more if the bid is rescinded than if Hiss comes here as scheduled.” The paper termed the choice “the lesser of two evils,” complained about Princeton’s “stigma of being powerfully influenced by its alumni body,” and argued that to re-tract the invitation now “would imply that Princeton is an institution which can be browbeaten by outside pressure groups.”

This last comment gained wide publicity, and disturbed alumni who regarded themselves as very much a part of the Princeton family, not as an “outside pressure group.” At a stormy meeting of the Graduate Council a student upset the group’s chairman, Chandler Cudlipp ’19, by saying, “We’re going to show you who runs the university.” Cudlipp expressed the core of alumni objection, the feeling that Hiss’s setting foot on the campus would be “desecrating the sacred grove.” Council secretary Griffin says, “This feeling was fading 20 years ago, and the undergraduates probably didn’t understand the language Chan was using.” It was also an emotional issue not refutable by logic. Says Gemmell, “This wasn’t just an-other college campus. A lot of alumni felt strongly about it as a place—to have their own home sullied by Hiss’s presence was personally repulsive.”

The Graduate Council backed the administration’s policy of not intervening but strongly urged it to persuade the Whig-Clio officers to rescind the invitation. Yet in Griffin’s view, “It settled down to a matter of alumni versus students, with the administration somewhere in between.” Most undergraduates agreed with their elders that the Halls officers had used bad judgment in engaging Hiss; at the same time, most were taken aback and bewildered by the reaction. As the pressure to cancel increased, however, the undergraduates began to see the issue as one of student rights. On Friday, April 13th, the Undergraduate Council unanimously approved a resolution supporting the administration’s position. While explicitly stating that it did not approve of Hiss’s record, the council asserted that a student organization, once given responsibility by the university, must be permitted to bear it, and that Whig-Clio “should not be subjected, at this time, to interference in its choice of speakers.”

The non-interference principle was not popularly received off campus. A Syracuse newspaper columnist wrote: “The view that college undergraduates should be allowed to get away with any kind of stupid, irresponsible thing they feel like doing is a basic tenet of modern Egghead philosophy.” Another commentator asked, “Isn’t the university going overboard for an abstraction, and compounding a practical blunder?” Mothers wrote in worrying about the corruption of young men’s minds. Patriotic and veterans groups called for cancellation “out of respect for the sensibilities of millions of fellow Americans.” A VFW chapter near Princeton called for the censure of Whig-Clio officers and urged courses in “etiquette, logic, American history, and Americanism.”

Alumni groups across the country passed resolutions censuring Whig-Clio and demanding administrative action. The Alumni Association of Northern New Jersey appealed directly to the students with a prominent Prince advertisement that urged in bold type: “Think It Over, Whig-Clio.” The text argued that besides discrediting Princeton and hurting annual giving, the speech would “reflect on you as individuals. How does this balance with your increase of information on the Meaning of Geneva?” In a letter to the Halls, the alumni group said, “A convicted perjurer has no place in the Princeton family under any auspices.”

Nonetheless, the university got a boost when Adlai E. Stevenson ’22, on the presidential campaign trail in Florida, commented, “If the students choose to invite him, that’s the students’ business.” (Stevenson, incidentally, was a friend of Hiss and testified as a character witness at his trial.) The Washington Post, in its Sunday, April 15, edition, came out as the first major-media defender of the administration, citing “poor judgment” by Whig-Clio but praising Dodds’s “wisdom.” James Wechsler of the New York Post cabled, “Both the Republic—and Princeton’s student body—can survive any lecture by any-one.” And the following week the number of supportive letters began to increase.

Upon his return from South Dakota, Bringgold conferred with the other Whig-Clio officers and then informed the ad-ministration that they were determined to follow the invita-tion through to the end. By this time, however, it became privately known that Hiss himself was much disturbed about the opposition he had aroused, and he arranged through a friend at the university to negotiate a possible withdrawal. Howell, who was present in the Nassau Hall office where a tense Bringgold took the call, reconstructs the conversation:

HISS: Are the officers of Whig-Clio still of a mind to have me accept their invitation to speak at Princeton?

BRINGGOLD: The officers of Whig-Clio stand behind their invitation to you, Mr. Hiss.

HISS: Then I’m coming.

Despite their disappointment that the event was not called off, university officials were genuinely proud of Bringgold’s performance. He had undergone weeks of extreme pressure from administrators, alumni, students, and outsiders. He had been barraged with hundreds of messages, from wires saying “Why don’t you go to Moscow University?” to long pleading letters from Whig-Clio trustees. Yet he kept his composure, even though it came to the point that he began to worry about the incident’s effect on his later life, future wife, and children. (Bringgold and his three children were later killed in a plane crash; only his wife survived.)

In the case of some Whig-Clio officers, parental pressure was also intense. In a real test of in loco parentis, an anxious Senator Stennis called Dodds to ask that he get his son to with-draw the invitation. “Well, Senator,” Dodds replied, “he’s your son, and if you want him out of this, you’ve got to do it yourself.” Father Stennis apparently respected the president’s hands-off policy and adopted it himself, even though it was politically hazardous for him.

While the flood of protest continued unabated, the ma-jor concern on the administrators’ minds now was the regular meeting of the Board of Trustees, scheduled for April 20, just six days before Hiss’s speech. Rumors were thick about dissension among the predominantly conservative board members, and though Dodds was, in the words of one aide, “at the peak of his personal authority,” no one harbored any illusions that it would be easy to persuade 31 establishment leaders to back a stand they found at the very least unpalatable. Most of the preparatory ground work for the meeting was done by Harold Helm ’20, then chairman of the trustees’ Executive Committee, who was in close consultation with Nassau Hall throughout the affair. He later cited the Hiss experience as the one that challenged and broadened him more than any other during his long association with Princeton.

But it was fellow trustee Harold R. Medina ’09—the federal court justice for southern New York then prominent for pre-siding over the widely publicized trial of 11 leaders of the American Communist party in 1949—who was the key administrative ally that day in the faculty room of Nassau Hall, where names like Rockefeller, Firestone, Lourie, and Osborn gathered for what the judge now calls “a great hullabaloo.” “Medina stood preeminent as a foe of communist conspiracy and defender of the Constitution,” says Gemmell. “It was providential that he was a member of that board.”

“A terrific battle it was,” says Medina of the three-hour session. It fell to him to satisfy the board that there were no “subversive implications or intent” on the part of the students and that the invitation was not part of a larger conspiracy. Once that was settled, the main debate ensued. At first it looked like the majority wanted to prohibit the speech, according to Medina. Dodds’s “educational principle” was advanced by an influential ad hoc committee of Chauncey Belknap ’12, Richard K. Stevens ’22, Helm, and Medina, who says he “backed Dodds up to beat the band.” Finally, on the understanding that the administration had been presented a fait accompli by the students, and justifying its policy “as a matter of educational principle,” the board unanimously disapproved the invitation and voted 26-4 (with one abstention) to “refrain from authoritarian censorship” and “to leave upon the students’ shoulders the responsibility for their action.”

At a press conference the next day, Gemmell said the university “deplored” Hiss’s appearance, and furthermore felt no responsibility to provide a forum for all views. “A college cam-pus is not Hyde Park on a Sunday morning,” he told reporters, and added that the question of freedom of speech did not enter into the consideration of the trustees when they voted not to interfere with the lecture. The only consideration, he maintained, was the taking of responsibility from the sponsoring organization.

Why was free speech, a cardinal principle today, apparently disregarded in 1956 in the key decision on whether a controversial figure would speak at Princeton? To Gemmell the tactician, the “educational principle” was the “strongest position” at the time. To a history professor who followed the proceedings, “It was the best way to take heat off the university and still have Hiss here. Free speech—the very words had a bad connotation in the minds of many of the men sitting on that board.” To an alumni leader, “It’s simple. The trustees were of the generation that believed in Princeton as sacred ground, and the only way they could accept his appearance was to take a ‘boys will be boys’ attitude.”

Medina, the judge, sees the decision as a triumph of First Amendment rights. Apple, the journalist, sees it as a “wise and courageous doctrine of civil liberty applied to undergraduates.” Hiss, the symbol, sees it as an “unexceptionable statement” thwarting the reawakened forces of McCarthyism. But Davies, PAW campus-watcher, thinks it was strange: “ ‘We wish to God that Whig-Clio would rescind that blankety-blank invitation, but we’re not gonna tell ’em to do so’—that’s not exactly defending academic freedom.” Wilson, the civil libertarian, concurs that it didn’t ring true: “If you believe in an open campus and intellectual stimulation, you don’t go around apologizing for it.”

Dodds elaborated his “educational principle” for the alumni in PAW: “We have sought to resolve this problem not in terms of ‘academic’ freedom but in the deeper and more subtle terms of human freedom. . . . One important element in education for human freedom is the freedom to make mistakes, and to learn to accept responsibility for them. . . . It’s often not enough to tell a child that fire is hot. To learn the personal significance of fire, the child must sometimes burn himself . . . I’ve never believed in education without tears, even when the tears must be shared by the teacher.”

The decision was widely criticized in the press. Popular right-wing columnist Westbrook Pegler asked, “What has got into these double-domes, anyway?” and termed Dodds’s state-ment “a potent argument against education and in favor of ignorance. Has he ever jumped out of a skyscraper to learn the personal significance of the law of gravity?” But a few papers saw real worth in the policy, among them the local Princeton Packet: “To eliminate the controversy and the risk would mean a supervision over student affairs to an extent that would contradict one of the basic purposes of college education.”

The most outspoken local critic was Father Hugh Halton, a founder of the Aquinas Institute and chaplain to Catholic undergraduates. The Sunday after the trustees’ meeting, he un-leashed a scathing attack from the pulpit, branding the policy “utter nonsense” and an instance of the “decline of moral and spiritual values at Princeton practically and speculatively.” He sermonized that “the mind should be treated as gently as the stomach. We don’t put poison in the stomach.” Halton, an acerbic and determined conservative Dominican, actually began his campaign the previous week, when he preached that the university ought to cancel the speech by fiat and regain powers which students “are incapable of exercising.” He had been battling the administration on philosophic and religious grounds for four years, charging Princeton with atheism and complicity in the subversion of spiritual values. His attacks on respected figures deeply divided Princeton’s growing Catholic community and made many powerful enemies, some of whom secured his ouster two years later by appealing directly to the Vatican.

A few days before the trustees’ meeting Halton had announced that he would bring a speaker to campus the night of April 25 as a counter to Hiss. The Chicago Tribune had previously expressed its dismay at the Hiss invitation and offered gratis the services of its Washington correspondent Willard Edwards, “if the Cliosophs want to hear an impartial estimate of Hiss and Yalta.” Halton took up the offer and arranged for Edwards, a leading anti-communist media figure who had covered the Hiss case for the Tribune, to speak on “The Meaning of Alger Hiss.” During his Sunday recitation of the Latin mass, Halton paused, hands beneath his chin, and implored “all who believe anything I have been saying for the past four years” to attend the Edwards rally. Asked afterwards if he foresaw any danger of a disturbance at the meeting, Halton replied, “Oh, yes. I expect all kinds of trouble.” Some Nassau Hall officials, who felt Halton was deliberately inflaming the situation, were furious. Princeton Theological Seminary President John Mackay regretted Halton’s “lamentable intrusion.”

In the days immediately preceding the Edwards and Hiss speeches, the campus was enveloped in an unwonted air of expectancy. Murray Kempton wrote, “This town crawls with more reporters than have been here since the Yale game was important to our national destiny. . . . The administration fears passion, and the reporters seek it.” (One fund-raiser quipped, “The boys can love Hiss, but they can’t hate Yale.”) Apprehension about the unexpected gripped insiders. One official noted his anxiety at the “crusading fervor aroused by an attentive press, alumni protests, congressmen, and priests.” He saw Princeton “caught in the eye of an emotional hurricane generated by the most controversial living American. No campus event in memory has conjured up such a host of dread possibilities.”

Bomb threats were telegrammed to Nassau Hall, as many as 10,000 patriotic and veterans marchers were predicted, and violence against Hiss was feared. “We had terrifying threats from the outside. The Jersey City American Legion wanted to come down here in buses and lay into the students,” Gemmell re-members. A goodly portion of the students were ripe to lay into the Legionnaires, too, Howell reports. It was spring riot season anyway, someone duly observed, and a local paper called the affair “a sideshow thing with riot possibilities.”

Whig-Clio closed the Hiss speech, allowing only 200 students and 50 press representatives to attend, and arranged for university radio station WPRB to broadcast both events to keep undergraduates in their rooms. The Hiss speech could not be transferred to a larger hall because that would strengthen his association with the university and all leaders wanted the most tightly controlled and quickest evening possible. To counter what Davies calls “the sheer emotional intensity” on the campus, President Dodds exhorted students to be on their best behavior and make their good con-duct “the answer to the skeptics.”

Meanwhile, reporters and television crews were combing the campus for news and color, interviewing any student in sight. Undergraduates were startled to hear their casually uttered comments being broadcast to the nation, and authoritative rumors of an eleventh-hour cancellation abounded. A press conference in Alexander Hall the afternoon before the Hiss speech drew more than 500 correspondents (40-50 had been expected), many from the foreign press. “It was a world-wide story—over what?” asks Gemmell. “The Germans, the Italians, Israelis, Agence France-Presse were all there. They didn’t understand, or thought it curious, that a ‘traitor’ was speaking before an important college audience.” As for the domestic media, he says, “I don’t know what the hell they expected to have happen.” One reporter asked if there were anyone who would not be allowed to speak at Princeton (something administrators had been asking themselves). Gemmell: “Yes. An agent provacoteur, probably.” Top correspondents from the domes-tic press covered the story, including Harrison Salisbury of The New York Times, Murray Kempton of the New York Post, and William Fulton of the Chicago Tribune. Former PAW editor Asa Bushnell ’21 drew the assignment for Town Topics, and the Daily Worker and American Legion News Service sent representatives.

Nassau Hall was worried that word of either the Hiss “withdrawal call” to Bringgold or the $100 speaking fee Whig-Clio was giving him might get out to the press. It was felt the news that “Princeton was actually paying a traitor” would set off an-other explosion, and administrators were incredulous that some-how it was not picked up.

Local hotels were jammed with curious outsiders and some alumni (“the curmudgeon contingent” as they were described by one administrator). This faction was to be heard at the Nass’ bar, grumbling about “Princeton in the Kremlin’s Service,” and lamenting the course of Princeton affairs since “that man Oppenheimer followed Einstein into Princeton.” Complained a visiting alumnus, “This is the last straw in the Princeton drift to eggheadism.”

Wednesday evening, April 25, a counter-revolutionary triumvirate took the stage of McCosh 50 for the anti-Hiss assembly the Prince thought “in questionable taste” and the administration had covertly tried to block. Father Halton, reporter Edwards, and Congressman Tumulty (putting in a surprise appearance), the latter two accompanied by their wives, were jostled, roundly booed and jeered by students as they entered the hall. The room was filled to capacity at 500—only about half of the crowd that sought admittance. Halton met a bar-rage of hisses and Bronx cheers as he mounted the podium for what one history professor calls “the climax of his unlimited warfare with the university.” To roars of laughter and catcalling that largely drowned out his speech, the militant priest pro-claimed the Hiss visit “Princeton’s darkest hour,” and “a dramatic expression of a spiritual crisis within the university.”

Groans from the feisty audience engulfed his claim that “the university has consciously abandoned its responsibility as a guardian of truth.” He got one big cheer: when he suggested that the students ought logically to invite “unrepentant prostitutes” to address them on “the meaning of purity.” Halton, who had earlier told reporters that he had received a thousand letters supporting his actions, and had charged that the university was trying to remove him from his post, bitterly informed the gathering that in at least one case, Princeton had censored a speaker: earlier that year it had blocked his own campus appearance as “too controversial.”

Tumulty, a 300-pound Irishman, followed in his abundant style, to continued (though somewhat more good-natured) jeering and boos, “weathering the gale as he would ignore a shower of empty beer bottles in Jersey City,” according to one writer. The orotund nephew of Woodrow Wilson’s personal secretary told the students he loved Princeton “more than you do,” and with salty jokes and thrusting admonitions berated them for inviting Hiss. He brought down the house and passed into Princeton legend by declaring that university officials ought to “spank you on your little red aspirations.”

After enthusiastically cheering the congressman, the crowd turned attentively to Edwards. The Tribune reporter said the invitation to Hiss was “Princeton’s business—not mine” (stamping and applause), and proceeded to give an hourlong account of Hiss’s career, involvement with Whittaker Chambers and at Yalta, and his testimony at the hearings and trials. Edwards warned students to beware the “urbane traitor,” and urged them to “give that amount of respect to his words which he has earned by his deeds.” After a respectful hearing, the students gave Edwards a standing ovation, and officials breathed with relief that the event had not triggered the feared repercussions.

“Bring on Grace Kelly!” yelled an undergraduate at the close of the meeting.

The university awoke the next morning to find hundreds of papier-mâché pumpkins littered by night across the front campus and the lawns of the eating clubs. Each symbolic jack-o-lantern had a roll of microfilm and a Woodstock typewriter picture inside—a reference to the secret documents Chambers had pulled from a hollowed-out pumpkin and used to charge Hiss with espionage. No one knew who was responsible for the prank, or for painting “traitor Hiss” in foot-high red letters across the front of Whig Hall and McCosh Walk. Angry calls from across the country came in all day, some threatening violence.

Precautions for Hiss’s visit, supervised by university treasurer Ricardo Mestres ’31, were exhaustive. Whig Hall was searched for bombs, closed at 7:00 A.M., and put under watch. More than 100 campus guards, uniformed municipal and state police, and plainclothesmen were on campus to bolster Princeton’s handful of proctors. Some 30 athletic coaches were made “deputy deans” for the evening to circulate about the campus and neutralize potential trouble by urging students back to their rooms. This policy, along with the local broadcast and restricted audience size, was intended to avoid the dreaded clash of stu-dents and VFW and Legion marchers. A network of checks on roads leading into Princeton was organized to give advance warning of the “rough set” if it came.

Hiss’s physical association with Princeton was to be as brief and low-profile as possible. The administration cancelled a planned post-speech reception, limited his talk to 20 minutes and questions to 10, refused to allow a press conference with him, and prohibited the press pool in the hall from asking questions. Said an administrator: “The amenities could not be observed with the usual graciousness.” To minimize popular association of Hiss and Princeton the press office even wanted cameramen to take their photos of Hiss against a non-Princeton or neutral backdrop.

During the afternoon, Richard Nixon, whose career had been launched with his prosecution of Hiss, announced that he would run again for the vice-presidency.

Whig Hall was “sanitized” again for explosives while Hiss had dinner with faculty friends at the guarded home of his-tory professor Elmer Beller outside Princeton. One guest re-calls that Hiss fell to talking excitedly about prothonotary warblers (this had been a famous piece of evidence that originally linked Hiss with Chambers): “I don’t think he realized what he was doing.”

The university’s cloak-and-dagger security kept Hiss’s whereabouts secret until he arrived by a circuitous route on the campus at 7:30 P.M., driven by Howard Menand ’36, now assistant dean of the Engineering School, and accompanied by motorcycle police and state troopers. Whig Hall’s Ionic columns were bathed in klieg-light glare as Hiss knifed his proctored way with “no comment” through the 700-strong crowd of students and press. Photographers, banned from inside the hall, were popping madly. A cheer went up from the students as Hiss passed through the front door. The expected protest demonstration failed to materialize (“Where are the Legionnaires?” students asked, as they milled about in a light mood outside).

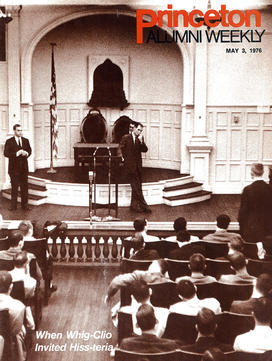

A gaunt figure with trembling hands spoke in a flat mono-tone to the tense audience inside the old Senate Chamber, bronze bas-relief of James Madison above his head and a full-length portrait of Woodrow Wilson staring down from the wall. “He seemed a rather tired and discouraged old man who had won a point by being invited to a university where he could speak,” recalls Howell. Hiss joked about his nearly causing “a second battle of Princeton,” and discussed the Geneva conference and its implications on world affairs. He quoted profusely, including the Pope, the Bible, and Senator Joe McCarthy. “The speech was duller than a New York Times editorial,” said Gemmell. A reporter groused, “The story ended when he walked in the front door.”

The evening was rescued by its thoroughgoing formality (Hiss recalls it as “measured dignity”). “How does one respond to a convicted perjurer and archsymbol of treachery, who is nevertheless a disarming guest, speaking innocuously at one’s own hotly-contested invitation, on a slightly boring subject?” asked The Reporter. To some polite questions (none on his case or Yalta role) Hiss said he didn’t believe Yalta was “such a pernicious occasion” and that, given the nuclear threat, international cooperation was a good thing. It was a speech with which “no Union League Republican could find fault,” commented the New York Journal-American. Hiss thanked the assembly for its courtesy, and students rose in an ovation “not quite spontaneous, not quite admiring—to a degree, pitying,” said one observer.

The evening’s real excitement came after the speech, when Hiss was whisked out the back door, into the president’s waiting black Cadillac, and off to New York. The throng of photographers out front was infuriated, and tried to stir up student emotion for their cameras. Some encouraged cheering, some threw cans at the students in the hope of getting a picture of them throwing the cans back—it depended on the paper’s bias. The New York Daily News headlined: “Princeton Hears Hiss Without Boom or Bah.”

Dodds and the trustees were praised two weeks later by the faculty in a unanimous resolution which cited the “wise and courageous leadership” that “brought the university through a trying period with dignity and honor.” The faculty had lain conspicuously low during the controversy itself, while every other imaginable group was in the act. With few exceptions, the professors said nothing publicly to support the administration under fire. Was it cowardly silence before a ram-pant McCarthyism, as was later charged? A professor-turned-administrator says, “My jaw sets whenever I hear that. It had nothing to do with McCarthyism; it was more comfy for them just to sit back. It revealed a narrowness and lack of commitment to the institution.”

J. Douglas Brown ’19, who was Dean of the Faculty in 1956, replies: “The faculty thought the affair greatly exaggerated. It was no decision, it was just business as usual. Freedom of speech is part of the academic process, deep in the consciousness of all faculty members. When you uphold tradition, your assumptions are what count, not belligerency.”

Dodds smiles: “If they supported me, they weren’t very vocal about it.”

The President of Colgate College, Everett Case ’22, told trustee Helm that Dodds couldn’t forbid Hiss “without bringing the wrath of the academic community down on his head.” One immediate plus from the affair, wrote another administrator: “Our prestige has never been higher in the academic world.” University officials everywhere congratulated Princeton for its stand. “We were watching you like hawks,” Finch was told by mid-western academics. “Had Princeton caved in, we would have been in trouble.”

In the aftermath of the Hiss speech there arose a dissident group, the Alumni Committee on Princeton Objectives, headed by Charles Whitehouse ’15 to “save freedom.” Whitehouse made an abortive effort to put in escrow funds from alumni whose “extreme revulsion” at the university’s handling of the matter prevented them from contributing to “those elements bent on its destruction.” At least one influential member of the Concerned Alumni of Princeton’s executive committee dates his disaffection from Princeton to the Hiss incident.

Financially, the affair generated as much support as opposition. While the university was struck from several wills, many alumni and friends were anxious to compensate, as in the case of one who sent Dodds a $5,000 check with the note: “It’s a terrible headache those boys are giving you. Here’s an aspirin tablet.” Gemmell thinks Princeton benefited because many alumni reacted to the criticism by doubling their normal contributions. The increase in 1957 Annual Giving figures, how-ever, owed mostly to a lot of extra work that year.

Princeton was happy to return to its private normalcy after the traumas of being thrust into the public arena. The controversy had revealed a number of cleavages, including that be-tween prevalent university and alumni thinking, which became clear when the administration failed to anticipate the dimensions of the reaction. Dodds’s stand was largely the story of the difficult defense of a subtle distinction. The interplay of pragmatic necessity and educational principle allowed Hiss to appear, on grounds not of free speech, but rather of the students’ “freedom to be wrong.” (“I subordinated my own expressed opinion of Hiss and insisted that students who had made a serious mistake work their own way out of it,” Dodds wrote in response to critics.)

Free speech had a relative value at Princeton in 1956, not the absolute one we know today. In the extreme instance of Hiss, the “welfare of the university” overrode other considerations. The “boys will be boys” approach succeeded in the face of a deep feeling about the campus as “sacred ground,” and the idea that Princeton was an honored podium conferring honor upon its guests. Nonetheless, student freedoms, and by indirection, free speech, emerged strengthened from the confusion. Most principle-finding came when the crisis was past, and after the defense had been made. The Whig-Clio officers and trustees “clarified” the prior consultation procedure, making it a matter of courtesy to inform the administration of prospective speakers. What remained to be clarified was the question of how far student freedom would go. The next 20 years were to struggle with that issue.

1 Response

Walter Menand

1 Year AgoInteresting Moment in History

Enjoyed the article. I guess I had heard that the speech was sort of anticlimactic after all the uproar. My father, who died in 2007, was Howard Menand ’36.