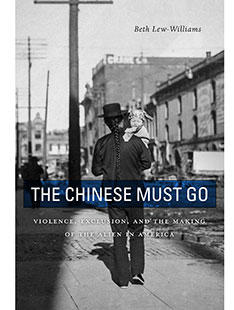

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred most immigrants from China, and subsequent legislation extended the ban to other Asian countries. In The Chinese Must Go (Harvard University Press), assistant history professor Beth Lew-Williams traces the roots of Chinese exclusion. She discussed the book — and how its historical insights might have foreshadowed the current immigration debate — with PAW.

How did the debate over Chinese exclusion shape our notion of citizenship?

Our concepts of “citizen” and “alien” were defined during the debate over Chinese exclusion. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, made citizenship something that the federal government defined, rather than the states. That led to drawing boundaries around citizenship, and the primary target was the Chinese. The result was border control for the first time and the idea that border control was a manifestation of national sovereignty and security. It also created the idea that aliens are permanent outsiders rather than Americans in waiting.

We have not seen violence against immigrants today as there was against the Chinese, or attempts to ban all immigration. Could we?

Federal immigration policy affects our perception of immigrants. That’s the parallel I fear today — that the rhetoric coming from the White House and actions like the travel ban and the zero-tolerance policy at the Mexican border will not only affect the people trying to come into the country but also Americans’ conception of who immigrants are and what threats they pose. I do think federal policy has the potential to feed local prejudice.

What have we learned over the last 150 years?

I hope we have learned that the power of cumulative forms of prejudice — not only a fear of racial minorities but also of lower-class working people, foreigners, and those with different religions — carries great weight. Too often we have a knee-jerk reaction against people who are different from ourselves.

I think we are now grappling with another fundamental inequality in our society, between citizens and aliens. Immigrants lack rights that American citizens enjoy, such as the right to due process and legal representation in deportation hearings. We can see the effects of that in all sorts of policies, most noticeably in the separation of families at the border.

Do you see any irony that Asians, who were once described as unassimilable, are now one of America’s wealthiest and best-educated minority groups?

I see irony when I view Chinese Americans who are very conservative and concerned about undocumented immigration. They are a growing minority within the Asian American community. Part of the problem is that recent Asian immigrants don’t identify with the 19th-century history. Because Chinese exclusion was extremely effective, most Asian Americans today, including most of my students, only date their history in America back for one or two generations. They don’t have a direct connection to the period I wrote about. Part of what I want to do is remind Asian Americans that the nativism we see today, which is aimed at other groups, was once aimed at them.

Interview conducted and condensed by M.F.B.

No responses yet