Being asked to write a piece about the greatest athlete in Princeton history, as selected by PAW’s panel of experts, would be intimidating for anyone, let alone someone who played the same sport at the same school. After all, Bill Bradley ’65 scored 2,503 points in just three seasons — a mark that remains the Ivy League standard. And as my teammate Jerry Doyle ’91 once graciously observed, it seemed unlikely that I could score as many points if I was locked in a gym overnight.

In thinking about Bradley’s legacy, and the impact it still casts over the program, I wondered about the sequence of events that brought him to Princeton. As I have gotten to know him over the years, I thought I would ask. Many of these details — published for the first time in Bradley’s estimation — are the result of our email exchanges.

Wooed by more than 70 colleges, he had initially committed to Duke. But just after his high school graduation, Bradley took a Cook’s Tour of Europe; his father, who did not graduate from high school and had never left the country (but was nevertheless the local bank president), had insisted.

Bradley covered Europe’s greatest hits: Paris, Florence, and most prophetically, the Great Quad at Christ Church, Oxford. During the return voyage on the RMS Queen Elizabeth, his tour companions (13 women) informed Bradley that Princeton regularly produced Rhodes scholar candidates. The wheels began to turn.

Later that summer, he played in the Ban Johnson Baseball League, which has produced multiple major leaguers and is in Kansas City, some 267 miles from his home in Crystal City, Missouri. While there, Bradley suffered a stress fracture in his right foot. He had to consider a life without either sport. Finally, on a Friday night after returning home from a date, he woke his parents: “I want to go to Princeton.”

To be fair, it was a different world. Today, top recruits regularly announce their college decisions on TV or social media. Back then, the process was less choreographed. A story is told about Dean Smith, then an assistant at North Carolina. He arrived (bringing his boss) unannounced on a Saturday at the Bradley home. Unfortunately, the recruit was at an overnight Boy Scouts camp.

Two days after awakening his parents, Bradley flew to Newark with a single suitcase, spending the night in Blair on a bed with no sheets. The next morning, he attended the opening assembly in Alexander Hall. Later that week, the balance of his clothes arrived, and he was ensconced in a room in Henry.

Coach Franklin “Cappy” Cappon was oblivious, until the two inadvertently crossed paths near Dillon. According to Frank Deford ’61, spurned Duke coach Vic Bubas regularly pantomimed ritual hari-kari when reminded that Bradley should have been part of the Blue Devils team that went to back-to-back Final Fours in 1963 and 1964.

By rule at the time, freshmen were not allowed on the varsity and instead played on the freshman team. Yet those games were often more popular than the main event. John McPhee ’53 described the Dillon stands in 1961-62 as “already filled” for the undercard. Freshman coach Eddie Donovan would select his lineup: “You. You. You. You ... and Bradley.”

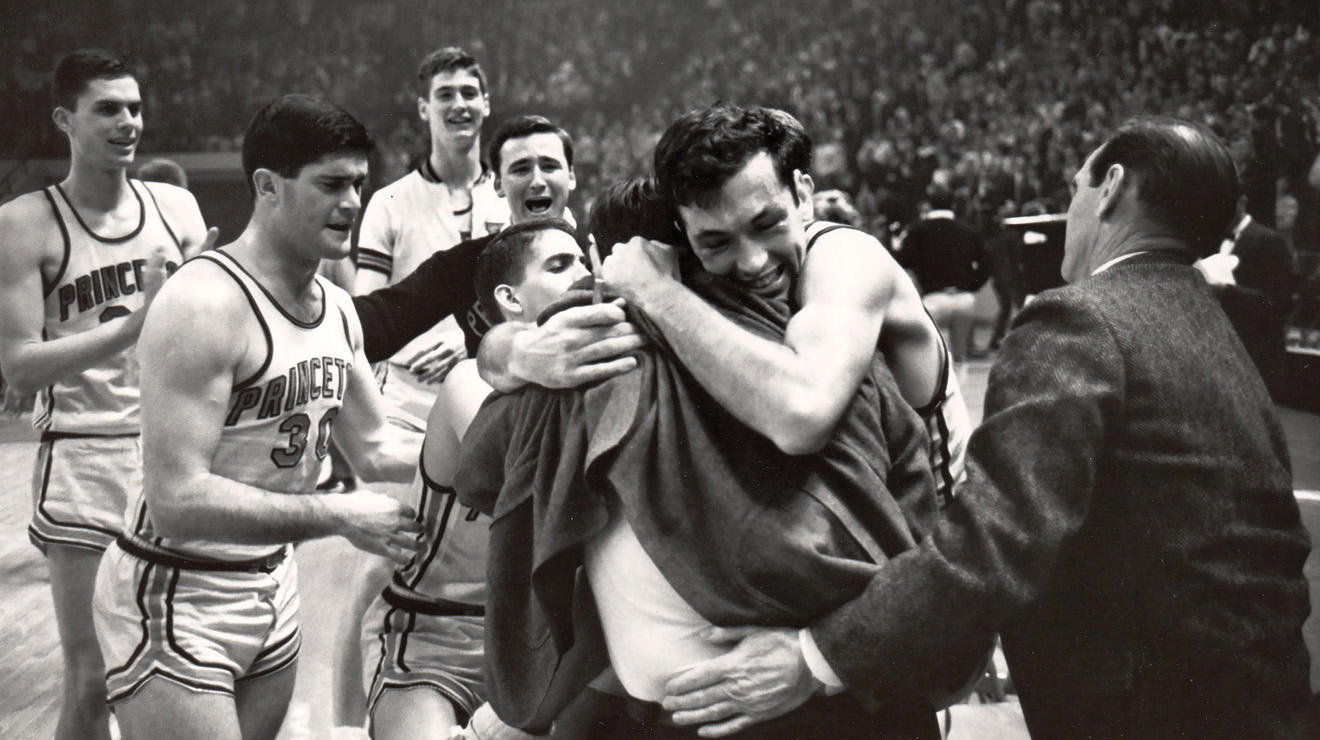

Cappon died of a heart attack in November 1961. Butch van Breda Kolff ’45 took over. Van Breda Kolff and Bradley were a match made in basketball heaven. Unlike his contemporaries, van Breda Kolff preached a freewheeling, open style of play — no set plays and maximum creativity. It suited Bradley’s talents.

To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, Bradley must have admired records because he made so many of them. He holds the single-game, single-season, and career average scoring marks for the Ivy League. He grabbed over 1,000 rebounds. (His assist totals remain unknown, as the statistic was not compiled until about a decade later; nonetheless, he was acknowledged as an excellent passer by those who saw him.)

The list of accomplishments goes on: Three-time first team All-American. Gold medal with the 1964 Olympic team. Most Outstanding Player in the 1965 Final Four. College Player of the Year. Later, after two years at Oxford, two championships with the New York Knicks and, ultimately, the Hall of Fame.

Less appreciated, perhaps, is Bradley’s Princeton legacy. The 1965 Final Four run became iconic. Jadwin Gym, which opened in 1969, was inspired, in part, by the overflowing crowds at Dillon; in the 1970s, the new gym was oft referred to as “the House that Bradley Built.” Van Breda Kolff leveraged his success with Bradley to jump to the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers; his final act at Princeton was to endorse Pete Carril (who had played for van Breda Kolff at Lafayette) as the new coach.

Carril, in turn, established his own Hall of Fame career, building on the van Breda Kolff-Bradley principles: movement, passing, and open shots. (Carril’s style became more deliberate over time; however, as Doyle would note — looking at me — he did make some recruiting mistakes in his later years.) Other than his immediate successor (a longtime assistant, Bill Carmody), Carril instructed every subsequent Princeton coach, from John Thompson III ’88 to Mitch Henderson ’98.

For more than 60 years, Princeton basketball has been built on the excellence set in the Bradley era. The slideshow is in our collective imaginations: The 1967 Sports Illustrated cover with Gary Walters ’67 and Chris Thomforde ’69. NBA Rookie of the Year Geoff Petrie ’70 in 1971. ABA Rookie of the Year Brian Taylor ’73 in 1973. The 1975 NIT title, led by Armond Hill ’85 and Mickey Steuerer ’76. The 1983 and ’84 NCAA runs. The 1989 Princeton-Georgetown game. The 1996 UCLA shocker. The early 2000s “Princeton offense” of layups and three-point shots that is now de rigueur in the modern NBA game. The 2023 Sweet 16 run. The entire Princeton basketball lineage can be traced back to that Friday night in Crystal City when Old Nassau supplanted Tobacco Road.

Matt Henshon ’91 practices law in the Boston area. He was recruited by and played for Pete Carril. He also worked for the Bradley presidential campaign in 2000.

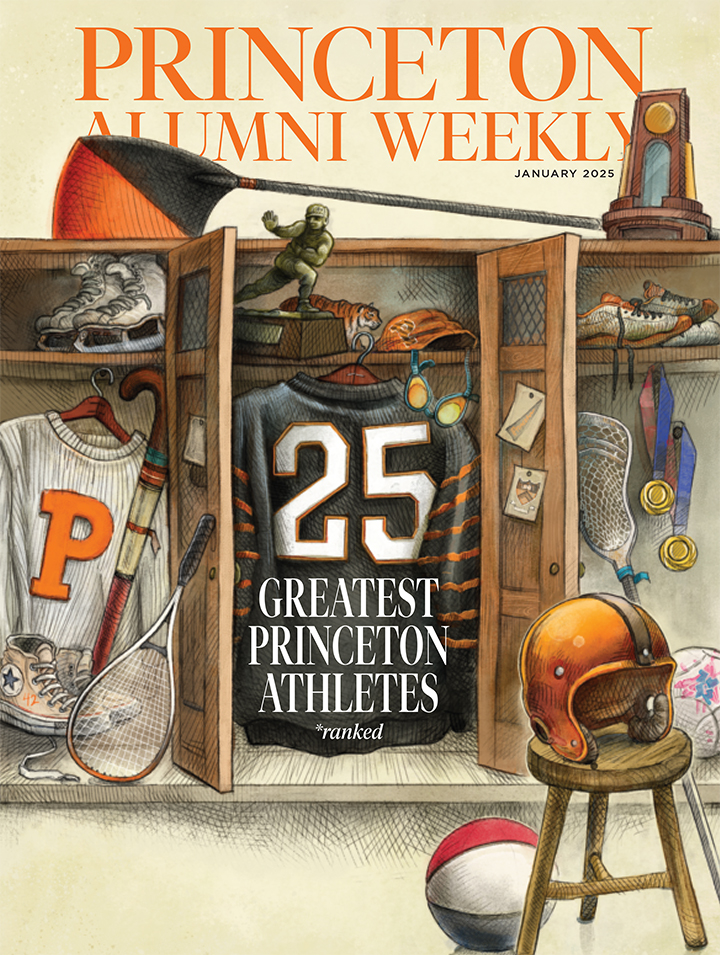

The 25 Greatest Athletes in Princeton History

#1: Bill Bradley ’65

men’s basketball

A lethal scorer who still holds Princeton records for most points in a career, season, and game, Bradley led the Tigers to three Ivy League titles and an appearance in the 1965 Final Four. The AP named him Player of the Year. As a professional, Bradley won two NBA championships with the New York Knicks. Both Princeton and the Knicks retired his number.

Bruce Roberts / Sports Illustrated / Getty Images

#2: Hobey Baker 1914

men’s ice hockey and football

Baker captained both the hockey and football teams at Princeton and was inducted into the hall of fame in both sports. On the gridiron, Baker, a punt returner and kicker, held the Princeton scoring record for 50 years. On the ice, he was known for his dazzling style of play as well as his sportsmanship, being penalized only once in his career.

Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

#3: Ashleigh Johnson ’17

women’s water polo

A three-time Olympian, Johnson won gold medals as goalie on the U.S. women’s water polo teams at the 2016 and 2021 Olympics. She has also won two gold medals in both the world championships and Pan American Games. At Princeton, Johnson became the first Princeton women’s water polo player to be named first-team All-American and graduated as the career leader in saves.

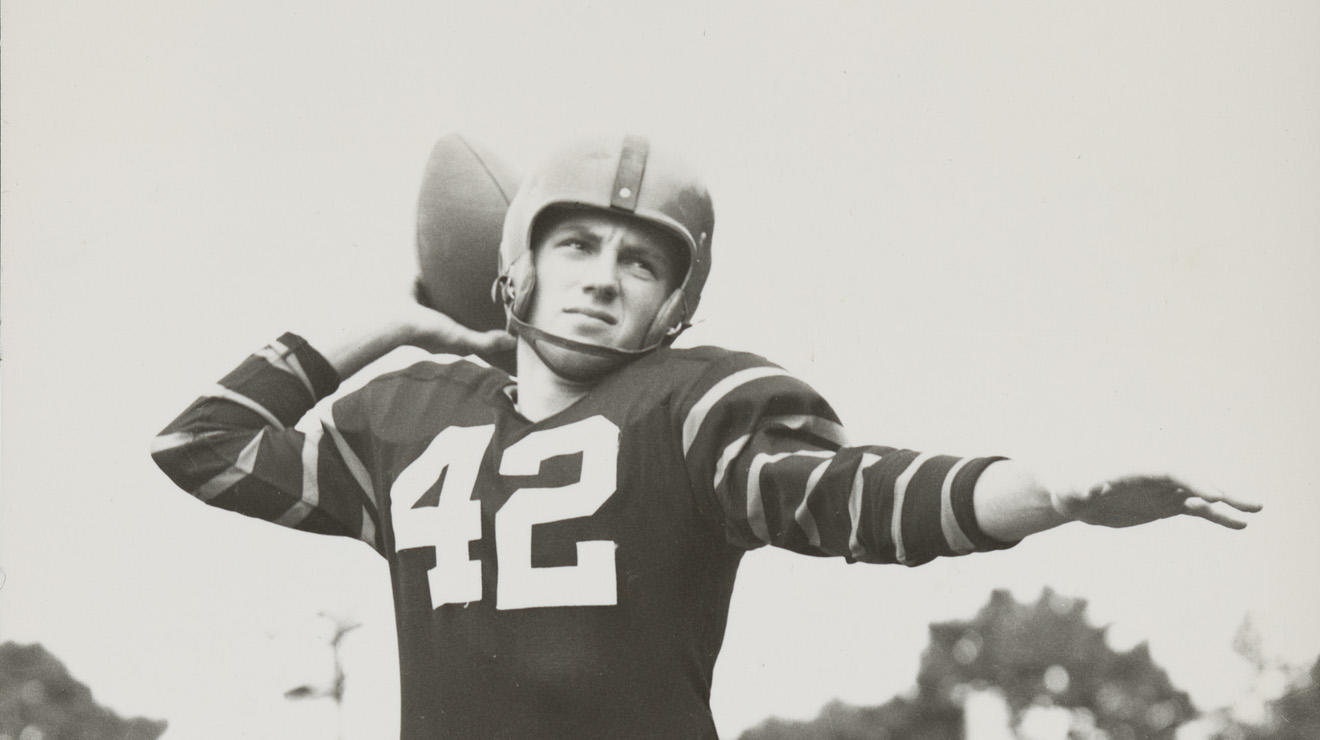

#4: Dick Kazmaier ’52

football

In 1951, Kazmaier became the only Princetonian and last Ivy Leaguer to win the Heisman Trophy. A two-time All-American at tailback in the single wing offense, Kazmaier led the nation in total offense his senior year and was also named the AP male athlete of the year. The University retired Kazmaier’s (and Bradley’s) number 42 for all sports in 2008.

Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

#5: Caroline Lind ’06

women’s crew

In 2006, Lind anchored a women’s eight that won a national championship for Princeton, winning all its races by more than 6.4 seconds. She won gold medals in the women’s eight at the 2008 and 2012 Olympics, as well as six world championships. Lind and her 2008 Olympic boatmates were inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

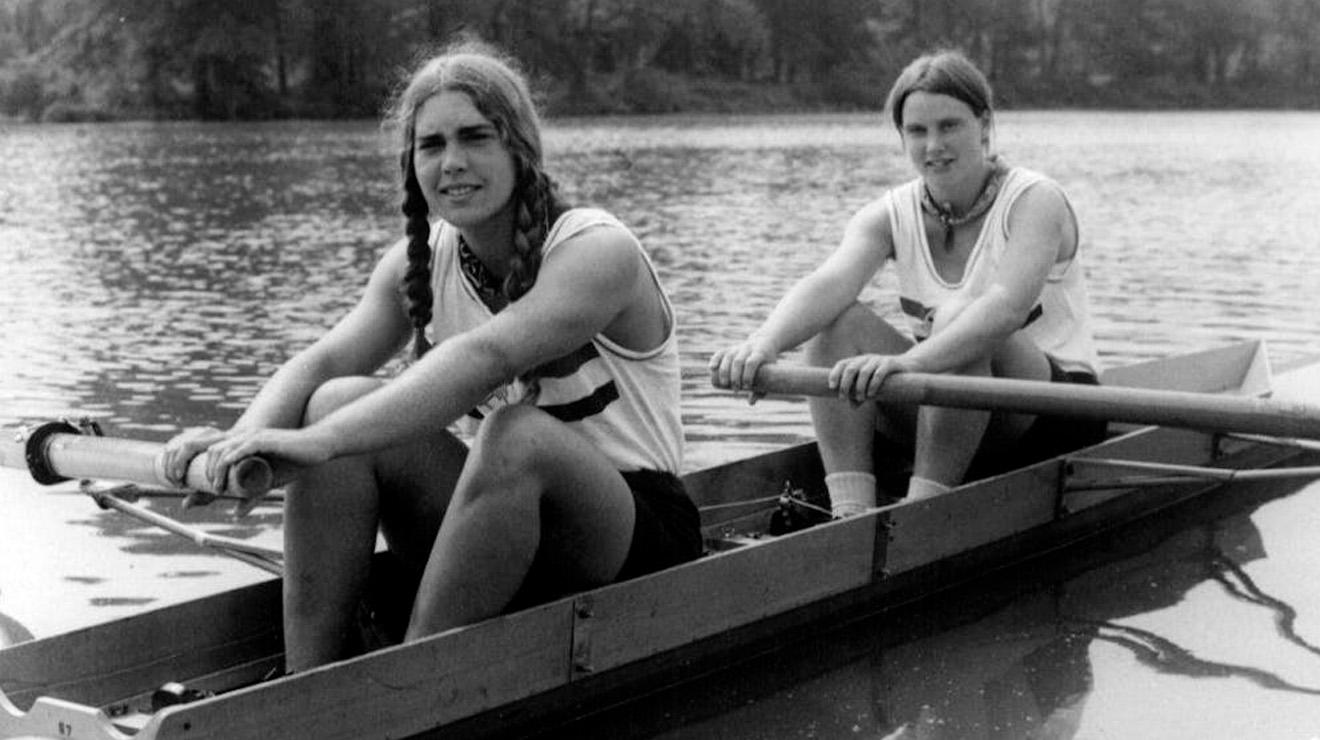

#6: Carol Brown ’75

women’s crew and women’s swimming

Brown (left) starred on Princeton’s women’s rowing team for three years, and she also swam and was part of a national record relay team in the 200-yard freestyle relay. A member of three Olympic rowing teams, Brown won a bronze medal in 1976. She was later inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

#7: Cathy Corcione ’74

women’s swimming

Corcione, who swam in the 1968 Olympics when she was only 15, helped found the Princeton women’s swimming program. As a junior, she set national records in the 100-yard butterfly and 100-yard freestyle, and the following year won national championships in the 100- and 200-yard individual medleys.

#8: Yasser El Halaby ’06

men’s squash

El Halaby (right) won the College Squash Association individual championship all four years, while leading Princeton to two Ivy League titles and two appearances in the CSA team finals. He would often draw standing-room crowds to his matches. Turning professional after graduation, El Halaby has been ranked as high as No. 40 in the world.

#9: Diana Matheson ’08

women’s soccer

An Olympic bronze medalist for Canada in 2012 and 2016, Matheson was named Ivy League rookie of the year and player of the year at Princeton. When she graduated, Matheson was Princeton’s career leader in assists — and now shares second place. She’s still the leader for most assists in a game (with four vs. Rutgers).

#10: Chris Ahrens ’98

men’s crew

Ahrens (pictured far left) represented the U.S. in the 2000 and 2004 Olympics, winning a gold medal in the latter. He claimed world championship gold medals in 1995, ’97, ’98, and ’99. And at Princeton, Ahrens was on the men’s heavyweight eight teams that won the IRA championship in 1996 and ’98.

#11: Chris Young ’02

men’s basketball and baseball

Young was named the Ivy League rookie of the year in both sports he played. He set two freshman records in basketball and doubled as the best pitcher in the Ivy League, leading the Tigers to an Ivy title in 2000. He was drafted before graduating and completed his senior thesis while playing in the minors. He won a World Series in 2015 as a starting pitcher for the Kansas City Royals.

#12: Rachael Becker DeCecco ’03

women’s lacrosse

Becker DeCecco (pictured at center, #25) was a three-time All-American and played on two NCAA championship teams. Her senior year, she won the Tewaaraton Award, college lacrosse’s top honor, and was the Ivy League player of the year. She still holds the Princeton record for career caused turnovers (171).

#13: Kat Sharkey ’13

field hockey

Sharkey was the Ivy League offensive player of the year her senior year, and also earned All-Ivy and all-NCAA Tournament honors. She holds the record for career points at Princeton (245), as well as goals (107), points in a game (six goals), and points in a season (38 goals, nine assists).

#14: Tom Schreiber ’14

men’s lacrosse

Schreiber, Princeton’s career points leader for midfielders, is a two-time winner of the MacLaughlin Award — given to the top midfielder in the NCAA — in his junior and senior years. He was a first-team All-American three times. As a professional, he has been named MVP of Major League Lacrosse three times, in 2016, ’17, and ’23.

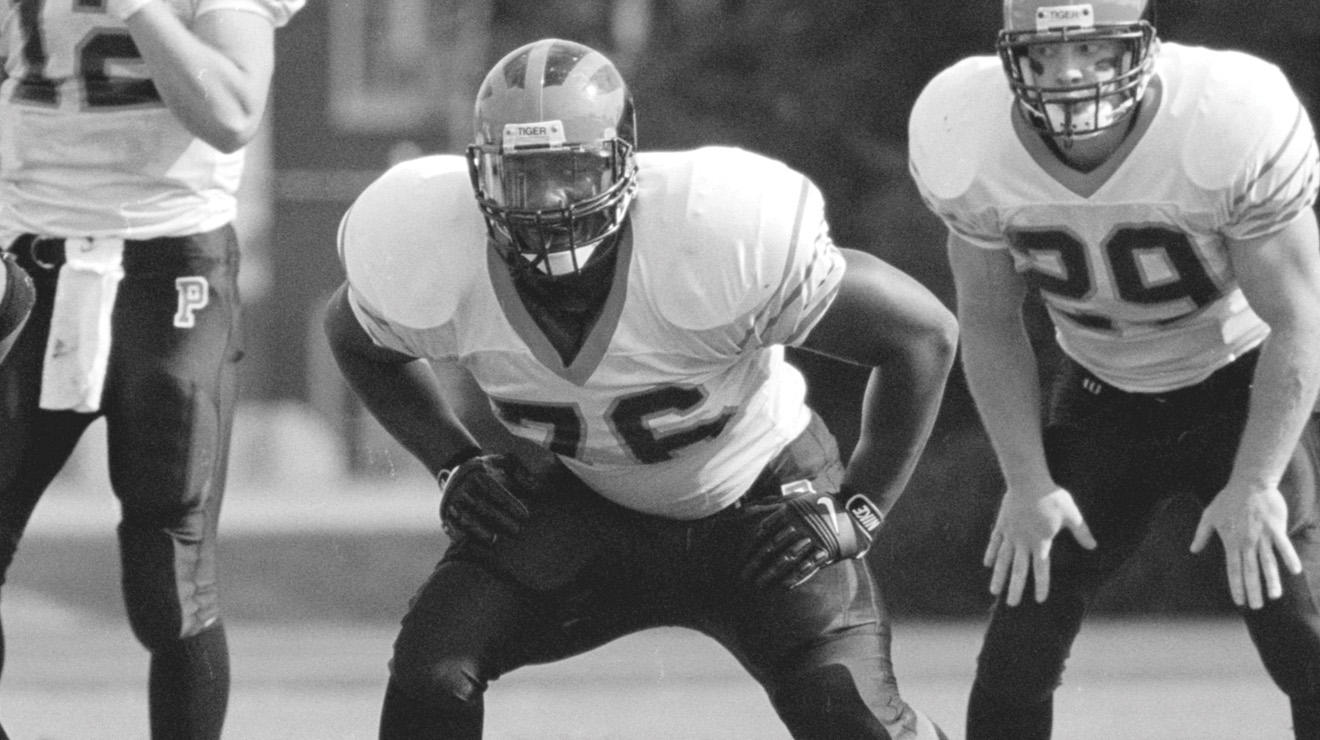

#15: Dennis Norman ’01

football and men’s track and field

Norman was named first-team All-Ivy three times before being selected in the seventh round of the 2001 NFL draft by the Seattle Seahawks. He played in the NFL for six seasons. As a track and field athlete, he won two Heps titles and holds Princeton’s fifth longest throw in the discus.

#16: Donn Cabral ’12

men’s cross country and track and field

Cabral was an All-American in steeplechase three times, twice in the outdoor 5,000 meters, once in the indoor 5,000 meters, and twice in cross country. He won the NCAA steeplechase championship in 2012. Cabral competed in the 2012 and 2016 Olympics for the United States and finished eighth both times.

#17: Demer Holleran ’89

women’s squash and women’s lacrosse

Holleran’s senior year was one for the ages: She won her third individual national title in squash (she’d also won in 1986 and ’87) and led the undefeated Tigers to national and Ivy team titles. She also starred as a goalkeeper in lacrosse, helping Princeton reach its first Final Four.

#18: Bella Alarie ’20

women’s basketball

Alarie, a high-scoring forward and towering defender, finished her career with 1,703 points and 249 blocks — both program records. She won three Ivy titles, but her chance to play in a third NCAA Tournament was dashed by the COVID pandemic. The Dallas Wings selected Alarie fifth overall in the 2020 WNBA Draft.

#19: Jesse Hubbard ’98

men’s lacrosse

A sharp-shooting attacker on Princeton’s three-peat national champions (1996, ’97, and ’98), Hubbard scored 163 goals, then the school record. He credited his prowess around the cage to countless hours practicing with teammates in “the pit” behind Dillon Gym. Hubbard also starred in the pros and won a world championship with the U.S.

#20: Sondre Guttormsen ’23

men’s track and field

Guttormsen set a new standard for Princeton pole vaulters, winning three NCAA championships (indoors in 2022 and ’23, outdoors in ’22) and a gold medal at the European indoor championships during his senior year. He’s represented his native Norway in the Olympics twice, including 2024 in Paris, where he placed eighth.

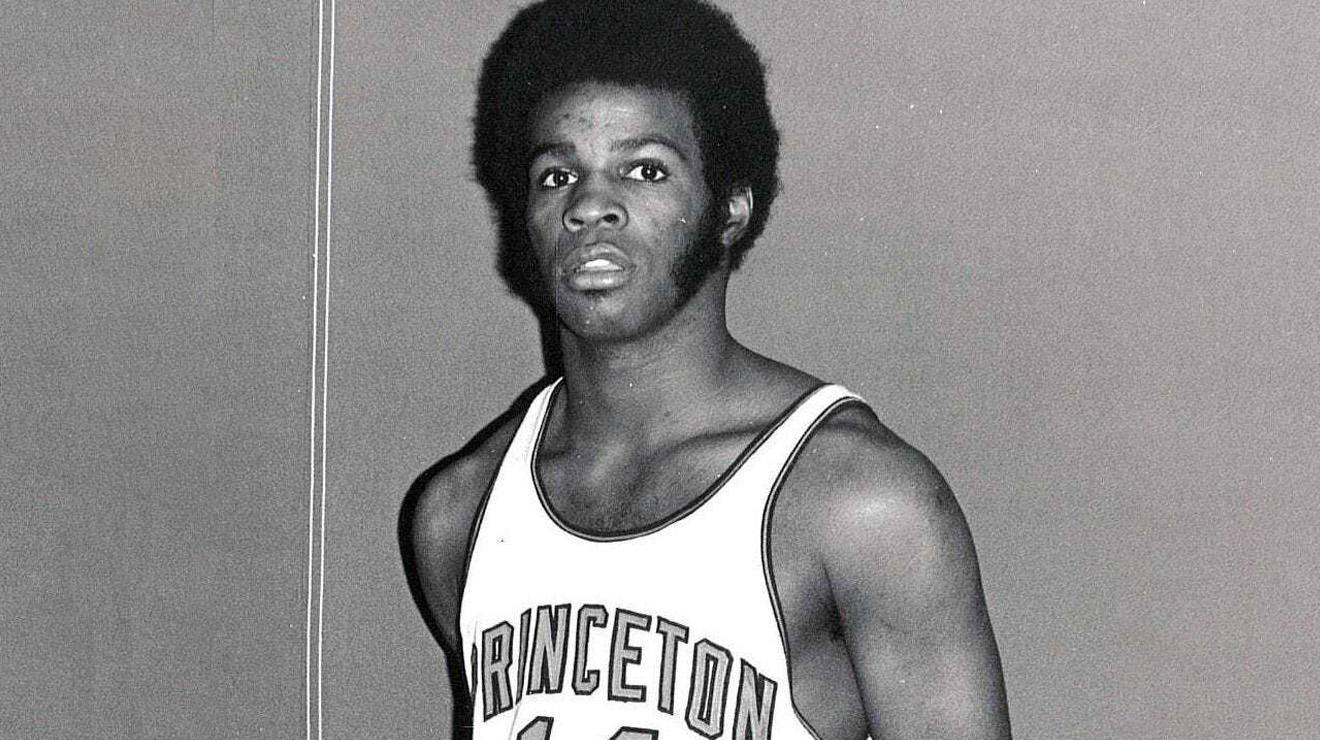

#21: Brian Taylor ’84

men’s basketball

Taylor averaged 24.3 points per game — second only to Bill Bradley ’65 — in two brilliant seasons at Princeton before leaving college early in 1972 to earn a living in the ABA (and later NBA). In 10 years as a pro, he was ABA rookie of the year and a two-time all-star and league champion. He returned to Princeton in 1983 to complete his degree.

#22: Anne Marden ’81

women’s crew

After rowing for four years on Princeton’s varsity eight, Marden switched to sculling and won two Olympic silver medals for the U.S. (quadruple sculls in 1984, single sculls in 1988). She also competed in the 1992 Olympics and, if not for the 1980 U.S. boycott, would have been Princeton’s first four-time Olympian.

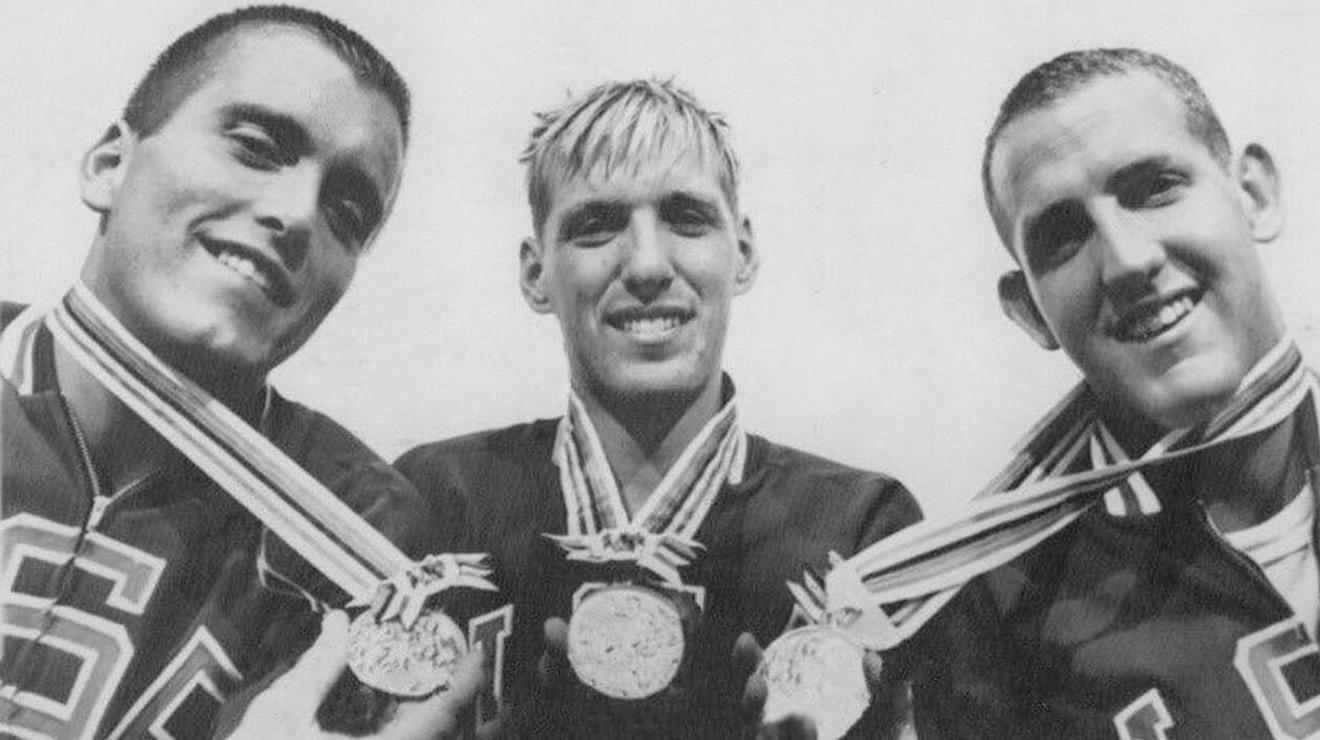

#23: Jed Graef ’64

men’s swimming and diving

The 6-foot-6 backstroke specialist’s enrollment was “the greatest thing that ever happened to Princeton swimming,” coach Bob Clotworthy told PAW in 1965, and that still may hold true: Graef won gold in 200-meter backstroke at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, months after capturing an NCAA title. He also held the world record in his event.

#24: Lynn Jennings ’83

women’s cross country and track and field

“The queen of hill and dale,” as Sports Illustrated once dubbed her, Jennings dominated on the cross country course, winning world championships in 1990, ’91, and ’92. She also starred on the track, running in the Olympics three times and capturing a bronze medal in 1992 (10,000 meters). At Princeton, she was the women’s cross country team’s first Ivy champ.

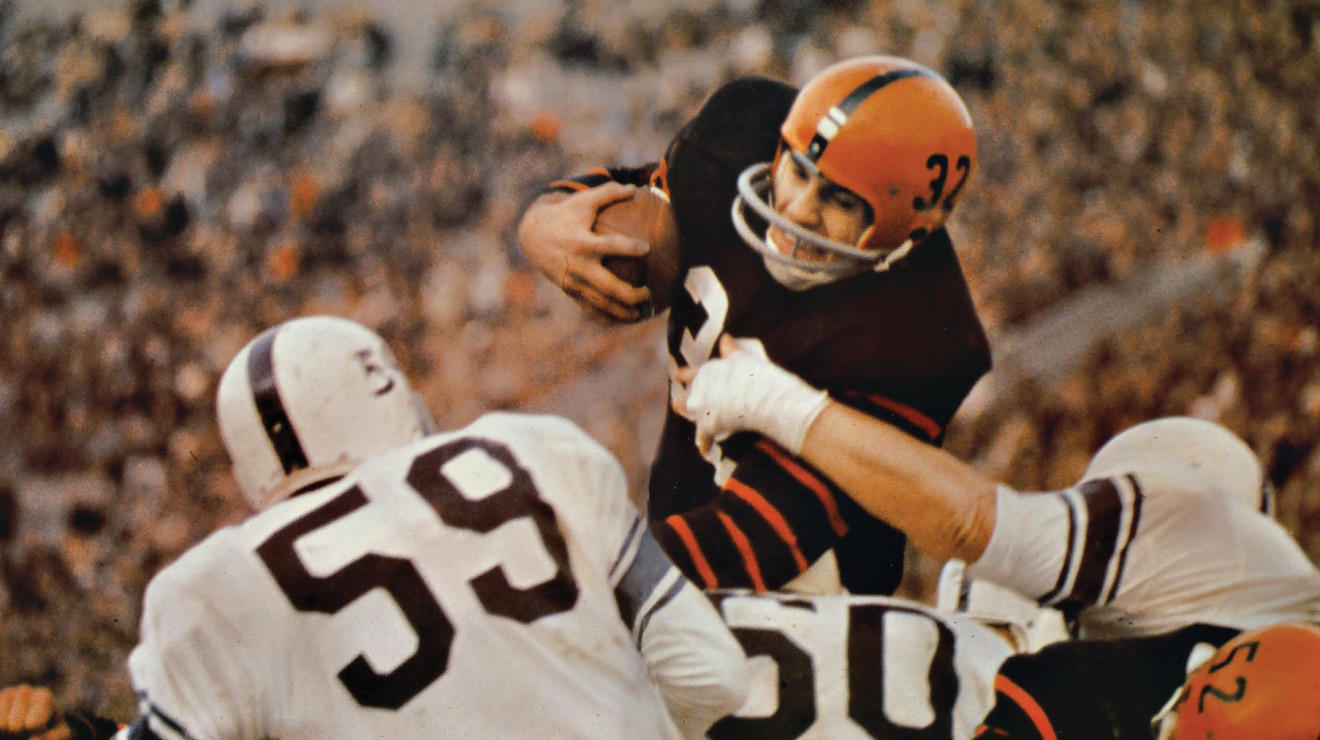

#25: Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65

football

Crashing through the line with an uncommon combination of power and speed, Iacavazzi supplanted fellow legends in the record books, passing Hobey Baker 1914’s career scoring record, which had stood for more than 50 years, and Dick Kazmaier ’52’s single season best for total yards. He captained the Tigers to an undefeated season in 1964.

1 Response

Robert E. “Bob” Buntrock *67

7 Months AgoBradley’s Extraordinary Court Vision

Thanks for this excellent saga of how Bill Bradley came to Princeton. From my brief time at Princeton as a chemistry grad student (1962-67), Bill Bradley is definitely the number one all-time Princeton athlete. My good friend and labmate Bob Carlson and I came to Princeton as chemistry grad students in ’62 with our B.Chems from the University of Minnesota. I was a non-jock but an avid fan, but Bob played high school ball.

One night in November, Bob said we should go to the home opener basketball game. He said that Princeton had a great sophomore player. I was skeptical (better than Ron Johnson at the U of M?) but went and was convinced. The team and Bill had a rough night but he eventually helped them pull out a win. We and our wives got season tickets the next three years and were rewarded with great basketball.

I still have memories of Bill bringing the ball down the court, head slightly down, and scanning, looking for the receiver of his next pass. We learned later in McPhee’s book that Bill had 150-degree peripheral vision. I’ve also been impressed with the rest of Bill’s careers.