On July 20, 1876, a few weeks after his graduation, Joseph McElroy “Mac” Mann 1876 won the shot-put competition at the first-ever championship meet of the Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America, held in Saratoga Springs, New York. Mann heaved a 16-pound shot 30 feet, 11.5 inches, a world record at the time. Even so, it was not his most enduring athletic accomplishment. Mann, a three-year starter on the baseball team, was one of the game’s early curveball pitchers and, in May 1875, threw the sport’s first recorded no-hitter.

Today, of course, Mac Mann is all but forgotten, and perhaps understandably so. Several others also claimed to have invented the curveball, 10 Tiger pitchers have thrown complete-game no-hitters, and the current Princeton shot-put record is more than twice as long (63 feet, 8.17 inches, currently held by Chris Licata ’22). Mann’s shot-put toss no longer even ranks among Princeton’s top 20. Sic transit gloria mundi, indeed.

Still, Mann was a hero in his day. Does he belong in Princeton’s athletic pantheon and, if so, where? Asking a broader question, who are the 25 greatest athletes in Princeton history? Who is No. 1? Get Tiger sports fans together and discussions like this will generate an argument. PAW decided to try to answer these questions.

It is not our first foray into this sort of project. Over the past few decades, we have attempted to select the most influential alumni ever (2008) and the most influential living alumni (2017). Copying our approach in those cases, we convened a panel of experts: current athletics director John Mack ’00, former athletics directors Mollie Marcoux Samaan ’91 and Gary Walters ’67, longtime sports information director Jerry Price, and ESPN investigative reporter Tisha Thompson ’99. One evening in late September, we all gathered at the Nassau Inn and attempted to hash it out.

From the outset, our panelists recognized that they had taken on a daunting assignment. Thousands have worn the orange and black since Princeton competed in its first-ever intercollegiate athletic contest on Nov. 22, 1864, a 27-16 loss to Williams in baseball. Over the 160 years since, Princeton athletes have gone on to outstanding professional careers, winning national and even international acclaim. They have set records, won medals, and had awards named for them. A few might even be said to have defined their sport or its association with Princeton in the national consciousness.

Still, today’s athletes are almost all bigger, faster, and stronger than their predecessors of even a few decades ago. They eat better, train better, and compete under better conditions. How, then, to measure greatness, and how to compare it between sports and across eras?

Forget apples and oranges, this is literally comparing squash balls and hockey pucks, not to mention oars, basketballs, footballs, and 16-pound lead shots. Sifting through a century and a half’s worth of outstanding Tiger athletes, winnowing out the 25 greatest, and then trying to rank them? It seems like an audacious, almost foolhardy undertaking, right?

Absolutely. So, let’s get started.

The 25 Greatest Athletes in Princeton History

As was the case with our two “Most Influential” rankings, the first task our current panel confronted was defining terms. What do we mean by greatness?

Winning an Olympic medal wasn’t enough. Princetonians have won 36 gold medals, 27 silver medals, and 26 bronze medals in the modern games. Hall of famers? We could almost have filled the list with just those inducted into the football (16) or lacrosse (17) halls of fame. First-team All-American? Impressive. First-team All-Ivy? Join the crowd.

After batting this question around, our panel decided that while there was no one achievement that defined greatness, they would look at everything a person did at Princeton or afterward (or in one case, before). Many of the University’s top athletes shone brightest after graduation as Olympians or professionals. But it only included what they did on the field of play, not on the sidelines, in the front office, or in the owner’s box.

Even within those broad parameters, our panel started with the acknowledgement that there were far more than 25 outstanding Princeton athletes. Like the admissions office, which sometimes says that it could replace its entire admitted class with the next tier of applicants and suffer no loss of talent, so could we have filled our list of great athletes several times over. This point cannot be emphasized enough: The fact that someone didn’t make the cut should not be read as a slight on their talent or team’s importance.

“If we’re ever going to get to 25, we have to get away from ‘This guy was great,’” Price argued. “They all were great. For this list, we’re talking about the elite of the elite of the elite.”

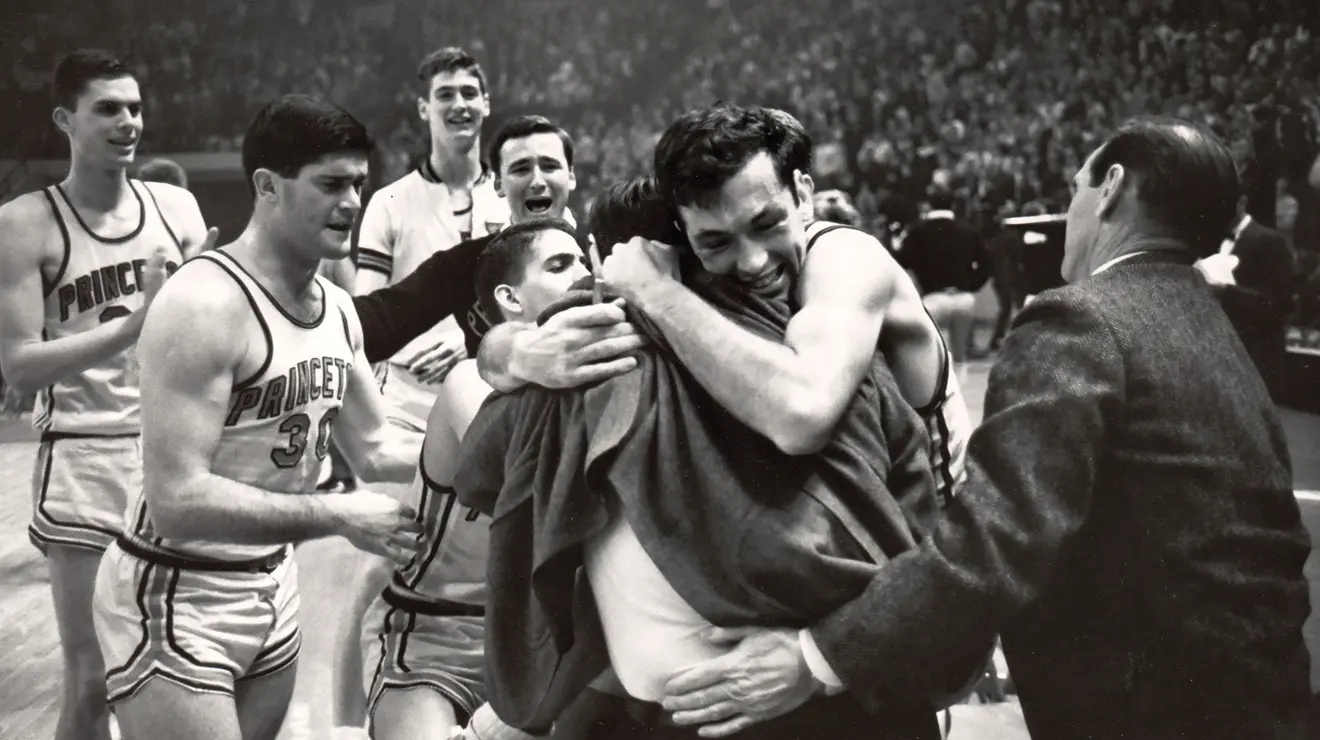

After those preliminaries, the panel’s top five came together rather easily. And so did its No. 1. Their consensus choice as the greatest athlete in Princeton history was basketball legend Bill Bradley ’65: A three-time All-American and Associated Press player of the year, he led Princeton to the NCAA Final Four in 1965, averaging 35 points per game. Bradley remains Princeton’s all-time leading scorer (playing when there was no three-point shot and freshman were ineligible for the varsity), and to this day no one has come within 478 points of him. He also won two NBA titles with the New York Knicks.

“When James Naismith invented basketball, Bill Bradley was the type of player he envisioned,” reads his entry on the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame website.

As that suggests, true greatness encompasses more than stats and honors; it also includes something ineffable. As Thompson put it, “It’s not just someone who was a great athlete. It’s someone who put Princeton on the map, so when you say their name, you think ‘Princeton.’”

That quality also characterized two of the next three names on our list: Hobey Baker 1914 (No. 2) and Dick Kazmaier ’52 (No. 4). Baker played on national championship teams both in football and hockey, and held Princeton’s football scoring record for 50 years until Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 (No. 25) broke it. Not only is he enshrined in both the college football and hockey halls of fame, there are two hockey awards named for him: the Hobey Baker Award, given to the nation’s best collegiate player, and the Hobey Baker Legends of College Hockey Award, given to an all-time great in the sport.

What lifted him to immortality, though, was not just what he did, but how he did it. Baker, wrote George Frazier in PAW in 1962, “haunts a whole school, and from generation unto generation. You say, ‘Hobey Baker,’ and all of a sudden you see the gallantry of a world long since gone ... .” Being idolized by F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 certainly boosted Baker’s status as a legend. So did dying tragically, when his fighter plane crashed in 1918, just a few weeks after the Armistice.

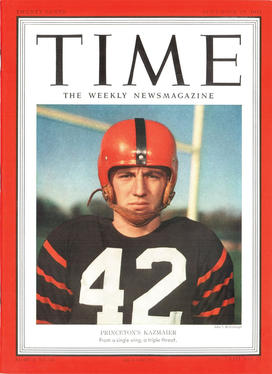

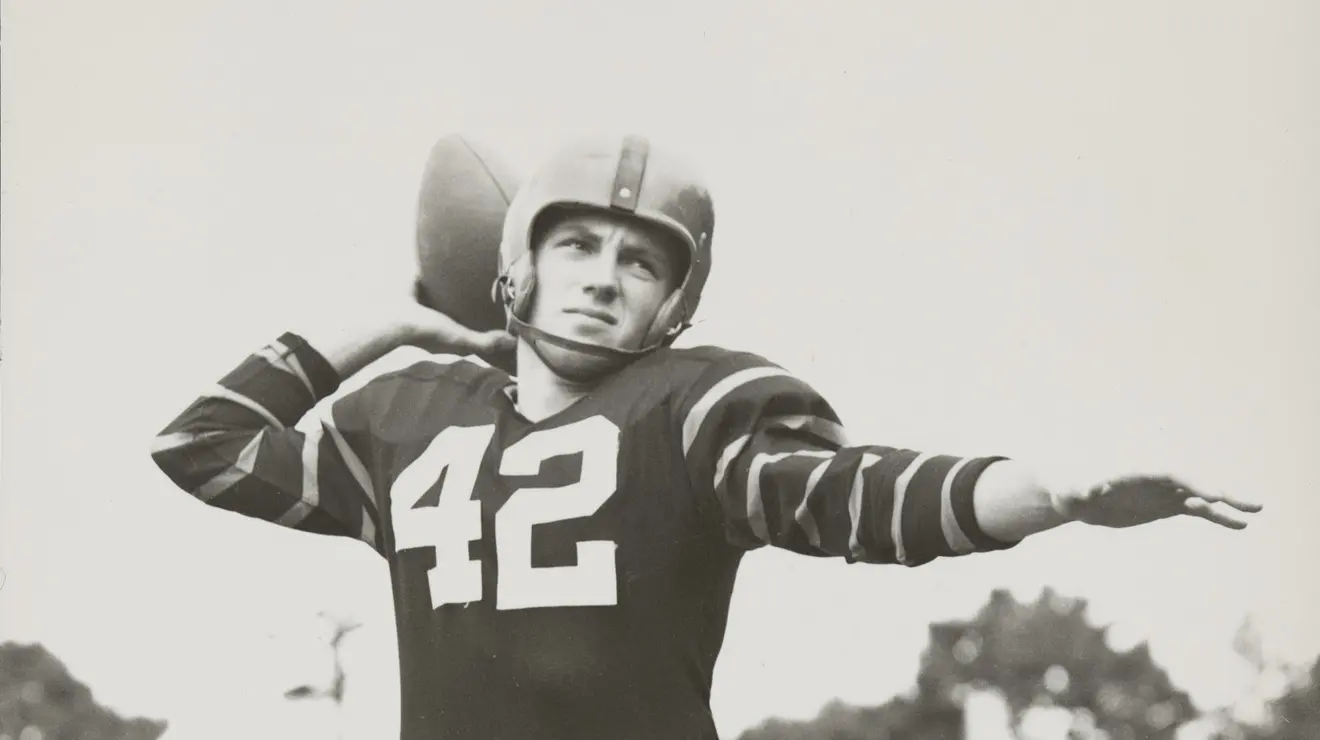

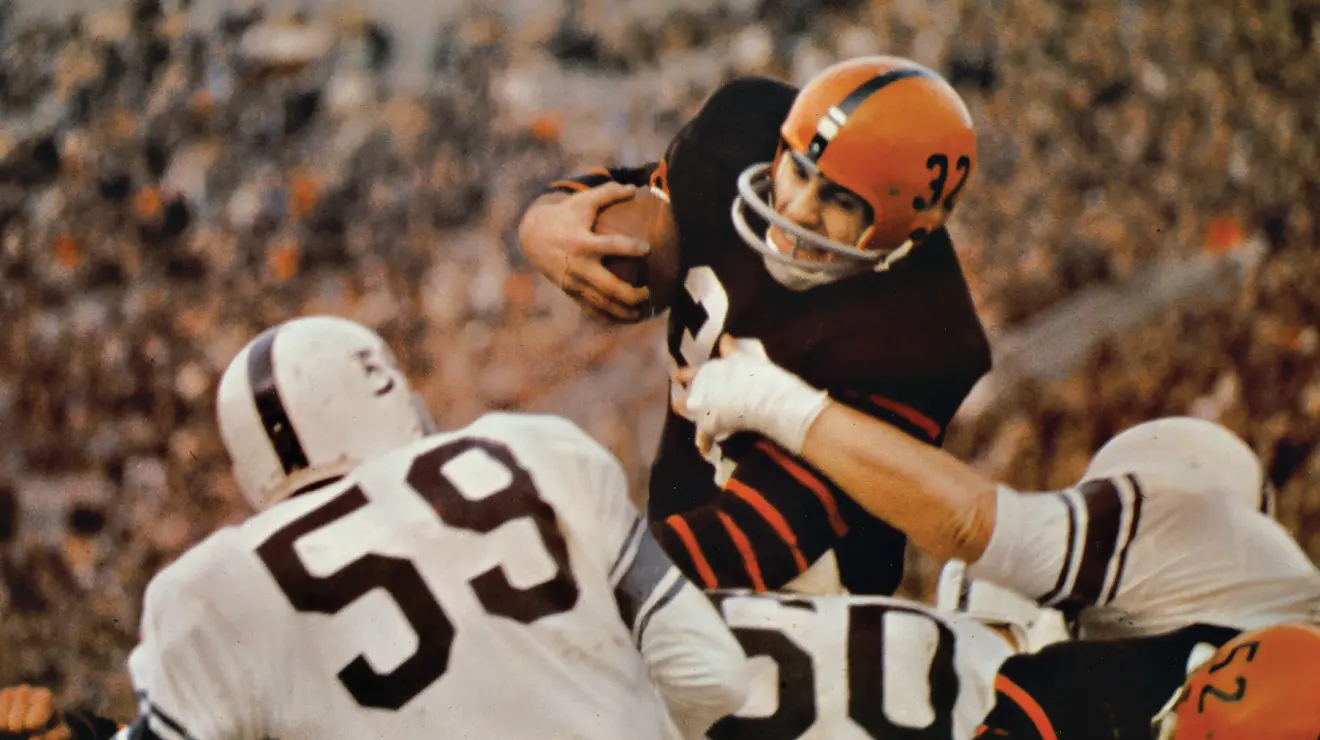

Kazmaier, likewise, is the only Tiger (and the last IvyLeaguer) to win the Heisman Trophy. It was not entirely a coincidence that he did so in 1951, when the nation was reeling from athletic scandals at West Point and elsewhere. Time magazine, which put him on the cover, called Kazmaier “a refreshing reminder, in the somewhat fetid atmosphere that has gathered around the pseudo-amateurs of U.S. sports, that winning football is not the monopoly of huge hired hands taking snap courses at football foundries.”

As Marcoux Samaan observed, Bradley and Kazmaier are the only two Princeton athletes to have statues outside Jadwin Gym and to have had their number (42) retired. That says they deserve to be at the top of the list.

The greatest female athletes on our list don’t have statues, though perhaps they should. Ashleigh Johnson ’17 (No. 3) is a three-time Olympian in water polo, leading the U.S. to gold medals in 2016 and 2021, and finished her career as Princeton’s all-time leader in saves and victories.

“If you ask people about the greatest water polo players of all time, they will say, ‘the Princeton goalie,’ even if they don’t know her name,” said Thompson. “She was a ceiling breaker. She’s done things for the sport that are sometimes intangible.”

Likewise, rower Caroline Lind ’06 (No. 5) won two Olympic gold medals and seven gold medals at the world championships in the women’s eight. Her boat senior year is regarded as one of the greatest ever, winning every race by more than six seconds. She and her 2008 Olympic teammates were all inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

These selections are the clearest possible evidence of the strength of Princeton’s women’s athletic program. Women have competed at Princeton for barely half a century, yet they make up 11 of our 25 greatest athletes, and half of the top 10.

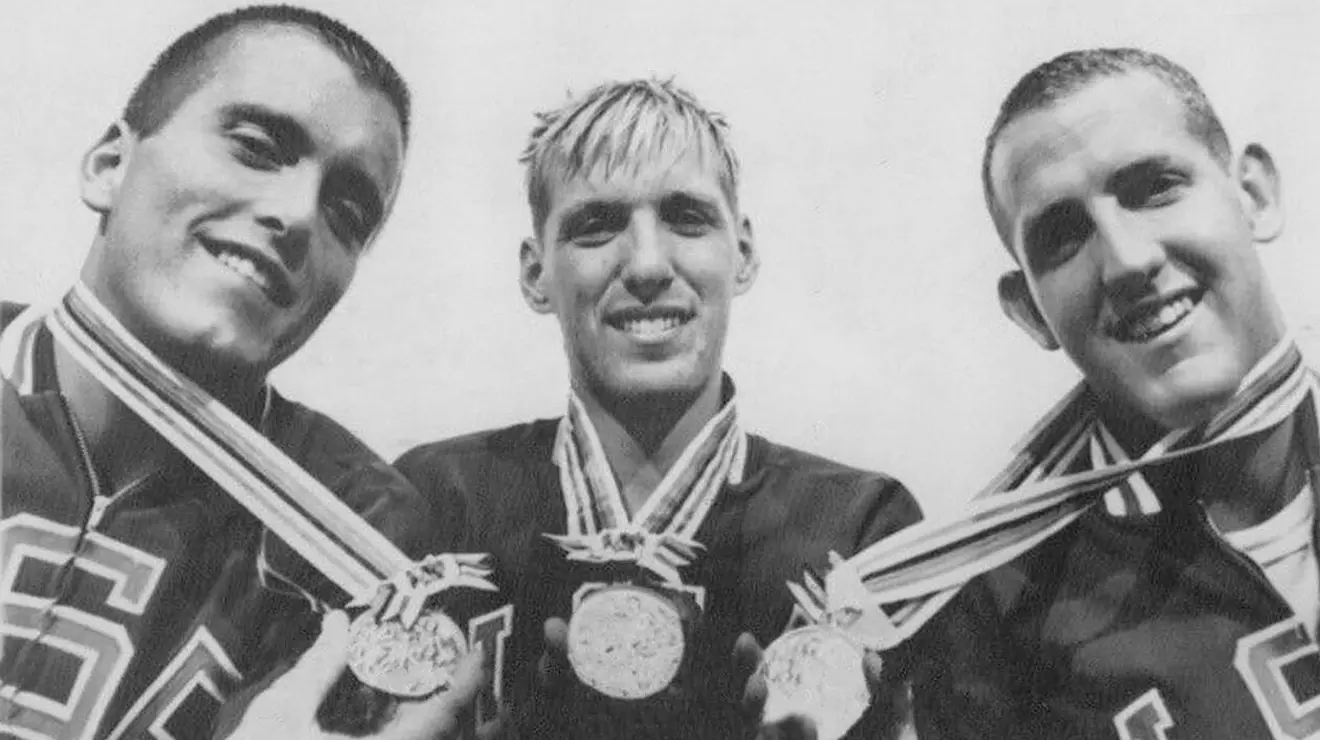

Two of them, teammates Carol Brown ’75 (No. 6) and Cathy Corcione ’74 (No. 7), were swimmers, and Brown was also a three-time Olympic rower. Corcione was an Olympian before she even got to Princeton, competing in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics when she was just 15. She helped found the women’s swimming program, setting national records in the 100-meter butterfly and 100-meter freestyle and winning four individual national championships. In 1973, she, Brown, Barbara Franks ’76, and Jane Fremon ’75 were part of a national record team in the 200-meter freestyle relay.

Add Anne Marden ’81 (No. 22), the only Princetonian to make four Olympic teams, with Lind and Brown, and women’s rowing placed three members on our list. Only football, with four, placed more.

So much of sports falls into the “could’ve, would’ve, should’ve” category. Dozens of athletes had their careers cut short by injuries, military service, or campus disruptions such as the COVID pandemic.

What might Chris Young ’02 (No. 11) have accomplished had he retained his eligibility at Princeton? He was named Ivy League rookie of the year in basketball and baseball, the only male athlete to do so in two sports. Yet he played for only two years, turning professional after he was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates. Young pitched for 14 seasons in the major leagues, making the All-Star team in 2007 and winning a World Series in 2015. Some argued that he belonged in our top five, citing the baseball and basketball records he might have broken had he played collegiately for all four years.

“We have to go by measurables,” Mack insisted. “What did he play, what did he win, what can we put down on paper? Not what would have happened or what someone might have gotten credit for.”

Fair enough. But it’s still fun to imagine.

In something of a surprise, the person our panel probably spent the most time arguing about never even wore a Princeton uniform.

Few readers have heard of William Libbey 1877. As an undergraduate, he helped get orange and black adopted as Princeton’s school colors. The summer after graduation, he went on a scientific expedition to Colorado, where he became the first person to climb what is now known as Mt. Princeton, a photo op in countless PAW Class Notes pages ever since. As a professor of physical geology, Libbey scaled mountains in Alaska, volcanoes in Hawaii, and glaciers in Greenland. He also won a silver medal in shooting at the 1912 Olympics, when he was 57 years old. Why isn’t he in our top 25?

“There’s lots of athleticism out there that’s not a traditional varsity sport,” Thompson argued. “To me, athleticism is more than just organized competition. I want one maverick on our list.”

While it was tempting to include Libbey, some worried how far we might be opening the door by doing so. What about others who excelled athletically yet never played for Princeton, such as Chloe Kim ’23 (who entered with the Class of 2023 but has not earned a degree), winner of two Olympic gold medals and eight Winter X Games medals in snowboarding, or Joey Cheek ’11, a three-time Olympic medalist in speed skating? Who else is out there we do not even know about?

In order to keep an already unmanageable task within bounds, our panel voted to adopt a stricter definition of athlete. “There is a distinction between Princetonians who have done great athletic things, and athletes who have represented Princeton,” Mack explained. “The first is an incredibly wide universe that we don’t have the ability to contain. People who have represented the University in athletic competition is a contained universe, and we can go through and process that list.”

Even so, more than two hours into our debate, we were still struggling to winnow that list of athletes to 25.

“Princeton is so lucky to have such an abundance of talent,” one of panelists said.

“I know,” another replied. “If this had been Brown, we’d have been done an hour ago.”

It seemed fitting to link Kat Sharkey ’13 (No. 13) with Tom Schreiber ’14 (No. 14). Sharkey is Princeton’s all-time leading scorer in field hockey, a three-time All-American, Olympian, and national champion. Schreiber was a three-time All-American in lacrosse and an MVP professionally. At Princeton, Sharkey scored 107 goals, while Schreiber scored 106. They were both outstanding athletes. They are also now married to each other.

Jesse Hubbard ’98 (No. 19) represents a Princeton dynasty in men’s lacrosse. The Tigers won six NCAA championships between 1992 and 2001, a period of dominance comparable to the UCLA basketball program under legendary coach John Wooden. Hubbard played on three of those championship teams, was a three-time All-American, and holds the school record for career goals scored.

“If you say, ‘Princeton lacrosse,’ Hubbard’s is the name that gets thrown back,” Thompson contended. Hubbard was also inducted into the U.S. Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 2012 and the Professional Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 2023.

In a few of the toughest cases, we had to split hairs. Consider two basketball stars of the Pete Carril era. Geoff Petrie ’70 was third on Princeton’s all-time scoring list when he graduated, while Brian Taylor ’84 was fifth when he left school to turn pro. Taylor owns the second highest career scoring average; Petrie is fourth. Petrie was the NBA rookie of the year in 1971 and a two-time all-star. Taylor was the ABA rookie of the year in 1973 and a two-time all-star. But he also won two ABA championships. That ultimately earned Taylor the nod.

Like athletic contests themselves, sometimes top 25 lists are a game of inches.

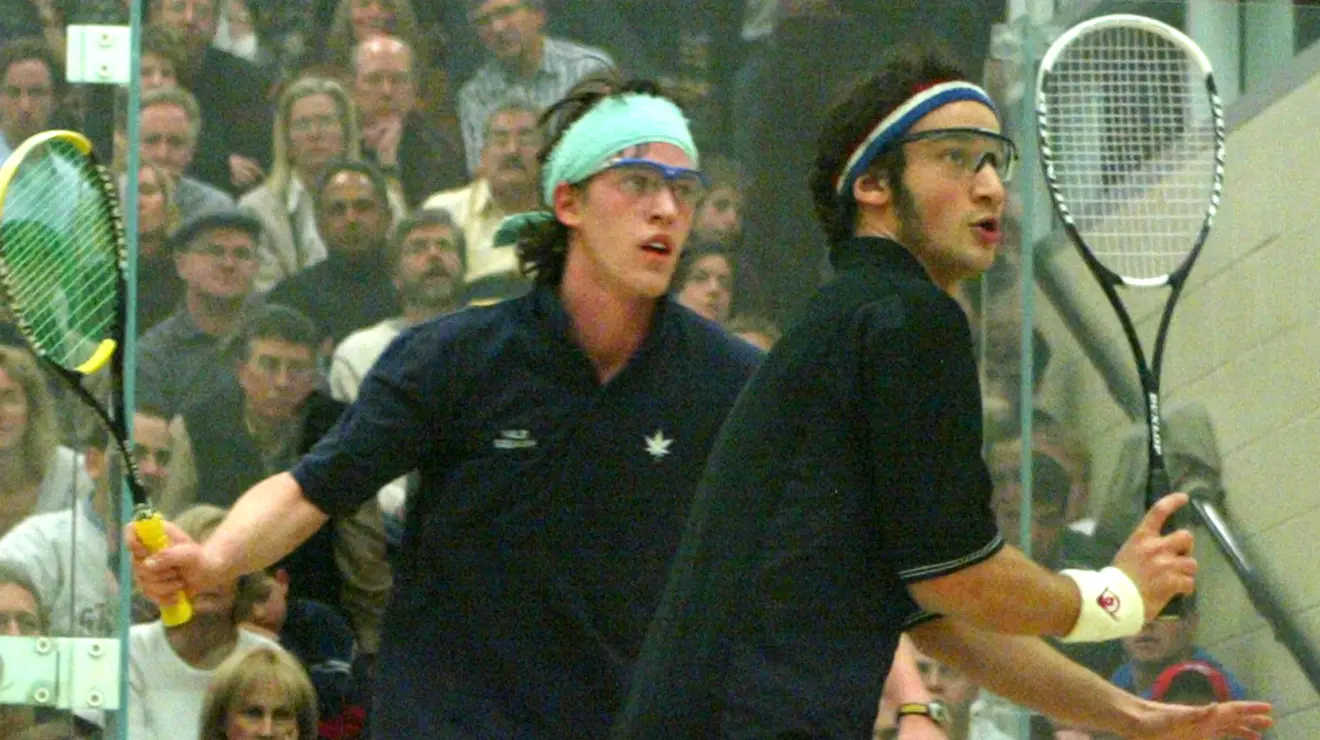

As with our other rankings, this list of athletes revealed some things about Princeton. An obvious one, as mentioned, is the success of the women’s athletic program. Another is the tremendous success of the entire athletic program in this century. Still another would be the growing internationalization of the student body. Two of the athletes on our list, squash champ Yasser El Halaby ’06 (No. 8) and pole vaulter Sondre Guttormsen ’23 (No. 20), were international students.

Inevitably, many incredible athletes fell short of recognition: John Van Ryn 1928, who won three consecutive Wimbledon doubles titles; Reddy Finney ’51, the first person to be named a first-team All-American in two sports in the same academic year; and Charlie Gogolak ’66, one of the nation’s first soccer style placekickers — to name just a few. How about Julia Ratcliffe ’17? She threw the hammer 134 times in Ivy League track and field competition and owned the top 134 hammer throws in Ivy League history when she graduated. Today, Ratcliffe no longer holds the Ivy League record in this event. Mac Mann would surely understand.

One difficulty in evaluating athletes across eras is that the structure of sports changes so much. In previous generations, the best athletes often lettered in multiple sports. In the modern era of specialization, hardly anyone plays multiple sports anymore. For that reason, give a locomotive for the versatile excellence of Emily Goodfellow ’76 and Amie Knox ’77, both of whom won an incredible 12 varsity letters during their careers. (Knox’s 12th varsity letter is a subject of debate, but we’ll give it to her.) How much more can a student-athlete do?

Although our panel took care not to judge athletes from previous generations by the standards of today, our list does show what social scientists call a recency bias. Eighteen of our 25 played since 1980, almost half since 2000, and nearly a quarter since 2010. Two have graduated within the last five years.

Princeton fields varsity teams in 38 men’s and women’s sports (only Harvard fields more), and according to the athletic department, more than half of undergraduates participate in some form of competition, either at the varsity or club level. Athletics remains an integral part of the Princeton experience.

The next generation of brilliant Tiger athletes is emerging right now, every week at Jadwin Gym, DeNunzio Pool, Baker Rink, the Shea Rowing Center, Class of 1952 Stadium, and other venues around campus. Just like their predecessors, as the old song goes, they will “fight with a vim that is dead sure to win for Old Nassau.”

You should come see them play sometime.

Now It’s Your Turn

Rearrange this list with this online tool, add your own athletes, and submit it to us. We’ll take all the answers and compile them into a readers’ choice list to be published on PAW’s website.

Have more feedback? Send us a letter using the form below.

1 Response

David McCarthy p*21

1 Year AgoBaker Cartoon’s Backstory

Kudos on an excellent January cover story (“Top Tigers: The 25 Greatest Athletes in Princeton History”).

The Franklin Collier cartoon of Hobey Baker 1914 and the Tigers trouncing the University of Toronto hockey team reproduced on the Contents page (cited as from an “unidentified publication”) ran in the Jan. 2, 1914, edition of The Boston Globe. The game was the lead story in the sports section. Baker and the Tigers were also the lead sports story of the next day’s edition of the Globe, with a photo montage and a preview of the Tigers’ upcoming match against the Boston Athletic Association. It’s hard to overstate what a big story Baker was in his day. Putting him as No. 2 in your rankings (just behind Bill Bradley ’65) sounds about right.