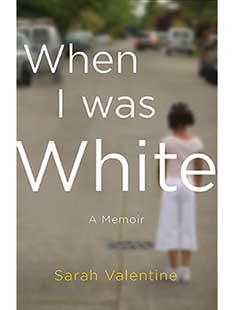

Her mother told Valentine (whose original family name was Dunn) that she was the child of a rape by an unidentified African American man. DNA tests confirmed that the man who raised her was not her biological father. The revelation almost undid Valentine, affecting her health, complicating her relationship with her mother, and prompting an unsuccessful search for her biological father. It also inspired a memoir, When I Was White (St. Martin’s Press). Valentine will visit campus Oct. 3–5 to discuss the book as part of the Thrive conference.

What inconsistencies were involved in growing up as a dark-skinned child in a white family and neighborhood?

The first was that I was clearly to everyone else a person of color. Every time I would be asked my background, all I had was the answer that I was white, that I was Irish and Italian. And I think that was probably very unsatisfying to most people. But I didn’t have any other answer to give. Believing I was white but constantly having my identity questioned from the outside really gave me a sense of split consciousness or double consciousness.

How did the revelation of your black ancestry affect you?

It was a shock. On the one hand, everything about me finally made sense, and in that sense, it was a huge relief. But it opened a whole Pandora’s box: Why has this been a secret until now? What does that mean for my sense of self? In what universe would parents lie to their daughter about her race and her biological parents? All of these things were overwhelming to deal with.

You crossed the color line just by regarding yourself differently. What does that say about the way we understand race in this country?

I started to reckon with my own racism — the racism I had internalized from my community and my family. It meant that I reflected very deeply on whiteness and how that operates in terms of racism and racial categories.

How has living as a black or biracial woman been different from living as a white one?

It really gave me a sense of living my authentic self. Both of those identities were denied to me growing up. I know some people consider mixed race as a separate identity. Socially, there is a sense that if you resemble a race other than white you are identified with that race — mainly because whiteness has always been exclusionary. If we didn’t consider mixed people black, we wouldn’t have had our first black president. We don’t really have a good way of understanding mixed-race identity in this country.

You write at the end of the memoir that you’ve been left with fragments, absence, loss.

I came to that conclusion because the biggest lesson I learned was that identity is something that is always in the making. I had to come to terms both personally and narratively with the fact that the story was not going to be finished in the way that I wanted it to be.

What are you doing now?

I’m working on a novel, and it’s very freeing to work on a story where I can decide the ending.

Interview conducted and condensed by Julia M. Klein

A version of this story appears in the Oct. 2, 2019, issue.

WEB EXCLUSIVE

Read more from our interview with Sarah Valentine *07 below.

Did your father believe he was your biological father?

When the DNA tests came back, it seemed like he was shocked – that he really had thought that I was his biological daughter. That’s hard for me to believe. Throughout this whole reckoning process, my dad was much more supportive to me than my mother was. His feeling was, “This doesn’t change anything. I’ll always be your dad.”

How did your experiences at Princeton precipitate your confrontation with your mother?

There were a lot of factors. There was the poet Yusef Komunyakaa, the first black teacher and mentor that I had ever had [for an undergraduate poetry workshop], suggesting that I attend a writing workshop for African American writers. I had been away from my family long enough that their narrative about me held a lot less sway. On campus, people related to me as a person of color. Being at Princeton put me in contact with so many people from different backgrounds that it made me feel that … if I did have an identity that was different than I grew up with, it was OK.

Your mother described you as a child of rape. Do you believe that?

I believe that she did experience a trauma and sexual assault. I still don’t know the extent of it. It’s something that she doesn’t want to talk about. She says that she doesn’t want to see herself as a victim.

You never did find your biological father. Have you abandoned that search?

Right now I am relying on the DNA search sites like Ancestry and 23andme to come up with potential relatives. None of my friends and family would help me beyond a certain point. At that point I had devoted enough of my energy to that pursuit. I couldn’t keep making that the focus of my life.

You recount having had an experience of sexual assault uncannily like that described by your mother.

Because I had had that experience, it was completely believable — [that one might] go to a party, get drunk, go into a room and pass out and wake up knowing something had happened, and not knowing who it was. That was what happened to me.

Your mother kept saying that race was “made up.” How do you feel about that?

Race is a social construction. I don’t think anyone would argue today that there’s anything essential about a person we would call black or white in terms of our brain function or anything. Then we have to ask ourselves, why is racism still such a problem? Why do we still have a society where whites dominate in positions of power? I think the reason is that social constructs are very deeply ingrained.

You renamed yourself for a Russian artist who painted a version of “The Rape of Europa.” Why?

It was very important for me to distinguish myself from the person I was who identified as white. So some kind of change was necessary — and giving myself a different last name was the clearest way I thought I could do that.

What’s the status of your relationship with your mother?

It remains tense. I think the difficulty is that neither of us can completely understand the other’s perspective.

No responses yet