It All Began with Butterflies

The Alumni Weekly provides these pages to the president.

Anyone who has attended a recent football game at Princeton will have noticed the imposing form of our future chemistry building southwest of the stadium. Abutting the wooded eastern edge of Washington Road and lying just south of Jadwin Hall, this fourstory, 263,000 square-foot-structure will take the place of Frick Laboratory and carry our chemistry department triumphantly into the 21st century.

Commissioned more than 80 years ago, Frick Laboratory is not only unequal to the technological demands of contemporary science, it is also a product of a time when the sciences were largely pursued in isolation from each other. In the fall of 2010, it will give way to a state-ofthe-art facility with centralized instrumentation, flexible laboratory space, and adjacent offices that are designed to foster collaboration within the field of chemistry, and a location that encourages collaboration with chemistry's scientific neighbors, especially molecular biology, geosciences, and physics. For our chemistry faculty, this building is a dream come true, a long-awaited opportunity to transform their workspace, to attract new talent in such areas as organic synthesis, chemical biology, and physical chemistry, and to pursue the complex questions that lie at the intersection of the sciences more effectively than ever before.

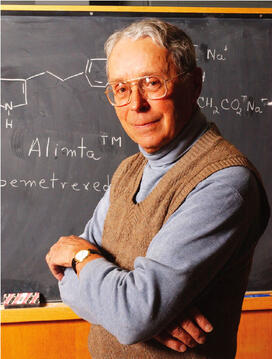

And for this we have butterflies to thank or, to be precise, the scientist whose curiosity they piqued. For the cost of constructing the new home of Princeton's chemistry department is being completely financed by royalties from a single drug named Alimta that was developed by Edward C. Taylor, the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Organic Chemistry, Emeritus. Ted, as he is universally known on campus, was a graduate student and aspiring chemist at Cornell University in the 1940s when he read an article that described a complex chemical compound found in liver, yeast, and spinach, and that was shown to be required for the growth of microorganisms. This socalled "liver factor" possessed a peculiar two-ring structural component that had been found a few years earlier in the wing pigments of butterflies, and this strange commonality so intrigued Ted that he decided to make these heterocyclic compounds the focus of his research. When scientists demonstrated that by altering the structure of the "liver-factor," which we know today as folic acid, the cell growth it enables could be halted, Ted knew that he had a truly important compound to study. Even more exciting was the ability of these altered compounds to cause remission in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a deadly childhood cancer. Unfortunately, they also adversely affected healthy cells, and refining the structure so that the growth-inhibiting properties were maintained without the debilitating side effects became a lifelong quest for Ted, first at the University of Illinois and then, beginning in 1954, at Princeton.

With remarkable persistence, he developed hundreds of chemical compounds in hope of finding one that would do the trick. Finally, he felt ready to approach the pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly with a potential candidate, and in 1985, he entered into a long and exceptionally fruitful collaboration with the company. In 2004, after more than a decade of clinical trials-and seven years after his retirement-the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Alimta for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma, a deadly form of cancer associated with exposure to asbestos. More recently, Alimta has been approved worldwide for both first- and second-line lung cancer, and many other forms of cancer have responded to this wonder drug in clinical trials. While Alimta does not constitute a cure, it has extended the lives of cancer sufferers and significantly improved their quality of life.

Ted, who, at the age of 85, still maintains an office in Hoyt Laboratory, rightly derives great satisfaction from the many thousands of lives that his research has improved. Very few drugs make it all the way to market, which is why Ted was named a Hero of Chemistry in 2006 by the American Chemical Society. He is also a hero to his colleagues in the chemistry department, for the royalty payments that the University derives from his patented discovery are going to help the next generation of Princeton chemists do path-breaking work. This is a magnificent legacy, and I cannot think of a better example of a scientist serving science in the broader service of humankind.

No responses yet