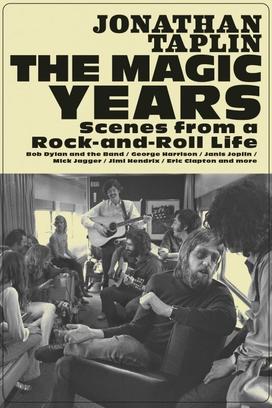

Jonathan Taplin ’69 Tells of his Extraordinary Magic Years

The book: The Magic Years: Scenes from a Rock-and-Roll Life (Heyday) explores the cultural shift from idealism to nihilism from the ’60s to today. Through writing about his experience as the manager of Bob Dylan and The Band in the ’60s, a producer of major films in the ’70s, a Merrill Lynch executive in the ’80s, and an internet trailblazer in the ’90s, Jonathan Taplin ’69 paints a vivid picture of life, art, and culture through some of America’s most culturally tumultuous — and formative — decades. Part memoir, part cultural criticism, The Magic Years charts how the nation moved the idealism of the ’60s toward the cynicism and nihilism of today. With his passion for the arts, Taplin explores major cultural shifts, how artists contributed to them, and how art holds the power to rekindle society’s sense of humanity.

The author: Jonathan Taplin ’69 is an American writer, film producer, and scholar. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and has lived in Los Angeles since 1973. Taplin is the director emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Most recently, Taplin authored Move Fast And Break Things: How Facebook, Google and Amazon Have Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy.

Excerpt (Princeton in Rebellion, 1967): Dylan and the Hawks were not going to tour, so I began working for Judy Collins as a road manager in the fall of 1967. She was tremendously popular on the college circuit, and we toured with two backup musicians, Paul Harris on piano and Bill Lee on bass. I would leave Princeton on Thursday night, get on a plane Friday morning, and do one college concert Friday night and another one on Saturday night. I’d be home in Princeton by Sunday evening. It was better than spending weekends swilling beer on Prospect Street, Princeton’s version of fraternity row.

Bill Lee (filmmaker Spike Lee’s father) and Paul Harris regaled me with wonderfully funny stories of the life of the journeyman musician. They were also personally protective of me, worrying about the looming draft after I graduated. Paul gave me the name of a shrink in New York who had written a long letter to his draft board explaining Paul’s inability to sleep in a barracks with a lot of other soldiers.

Bill made a very good living as a session musician, and he always had the best pot. One night we were on a double bill with the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Bill took Paul, myself, and Percy Heath of the MJQ out for a little pre-concert “meeting.” After about fifteen minutes of talking, laughing, and smoking, Percy complimented Bill on the weed: “This tastes just like the ‘long green’ that blew through Harlem in ’48.” I thought to myself, “There’s a man with a sense of history.”

Judy Collins’s manager was a wonderful old leftie named Harold Leventhal. Harold had been the manager of the Weavers, the original folk group that flourished in the fifties under the guidance of Pete Seeger. Seeger’s father was a distinguished composer and folk music scholar, and Pete had gone to boarding school and then Harvard. But in his sophomore year, he left. “I wasn’t sorry to leave Harvard,” he told the New Yorker’s Alec Wilkinson in 2006, “I was disgusted by what I considered the cynicism displayed by one of my professors. He would say, ‘Every society has a spring, a winter, a summer, and a fall,’ and scoff at us trying to stop Hitler. He said, ‘All you can do is accommodate.’ I was young and idealistic.”

In 1940, Seeger met Woody Guthrie at a “Grapes of Wrath” benefit for farmworkers. Guthrie and Seeger hit it off immediately, and Seeger invited Woody to join a communal singing group he had organized called the Almanac Singers. The group was a loose cooperative of people all living in what they named the Almanac House in Greenwich Village. All meals, chores, and rent were shared, and once a month the group would host a rent party they called a “hootenanny.” Along with Woody, the other regular members of the Almanacs were Millard Lampell and Lee Hays, and in classic socialist style they all agreed to share the song copyrights equally. But Woody wrote one song on his own during this period that would be his most lasting contribution to the American music canon: “This Land Is Your Land.” As war fever built during 1940, Guthrie told Seeger that he was tired of hearing Kate Smith’s version of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” being played over and over on the radio. The Berlin song did not represent the America he had seen traveling on railroad boxcars during the depression, so he wrote his own. The depth of his feelings for his country are apparent in this verse that’s hardly ever sung:

In the squares of the city, In the shadow of a steeple, By the relief office

I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry,

I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

Seeger had joined the Communist Party in 1936, and he often appeared with the Almanacs under an assumed name so as not to cause trouble for his father, Charles, who was employed by the Library of Congress as an ethnomusicologist. By 1942 Pete had joined the army and Guthrie had gone off to the Merchant Marine with his friend Cisco Houston. The Almanac Singers dissolved, although Seeger and Hays would reconstitute it after the war, but without Guthrie and under the name the Weavers. By the spring of 1950, the Weavers had a hit single with Lead Belly’s “Goodnight, Irene,” and by the end of the year they had sold four million copies of their first album.

But Seeger knew it was too good to last. In September of 1947 the House Un-American Activities Committee had subpoenaed forty-three Hollywood writers, directors, and actors to appear in early October to answer questions about the influence of communism in the movie business. The blacklisting campaign was aided by the June 1950 publication of the pamphlet Red Channels by an organization calling itself American Business Consultants Inc. (ABC), which claimed to be staffed by former FBI agents. For a hefty fee ABC would scrutinize the payrolls of the studios and TV networks to purge them of communists. Red Channels was their opening salvo, and in it they named 151 entertainers ABC claimed were “Reds.” The Weavers had just concluded a very successful engagement at the nightclub Ciro’s in Hollywood and were preparing their first network television show when their manager called to say that Seeger had been cited in Red Channels. “Red Channels came out,” Seeger told Wilkinson, “and the contract was torn up. I expected it, so I didn’t really feel resentful. We assumed that sooner or later they’d get us.”

For Seeger, the trouble with HUAC was just beginning. The Weavers disbanded, and essentially the commercial potential of folk music was put on hold for ten years. As much as I believe culture paves the way for political change, this period reminds me that a certain kind of authoritarian politics can block culture completely. If one imagines an alternative history in which Bob Dylan started his career in 1950 instead of 1960, would the Red Scare have buried Dylan’s genius? And if so, would the whole course of music have changed dramatically?

Reviews: “The Magic Years remarkably shares how Jon Taplin was on the front lines of so many pivotal and historic events. He has a helluva story to tell. I wouldn’t believe it if I hadn’t seen a lot of it with my own eyes.” —Robbie Robertson, of The Band

No responses yet