Jordan Salama ’19 On His Journey Up and Down the Magdalena River

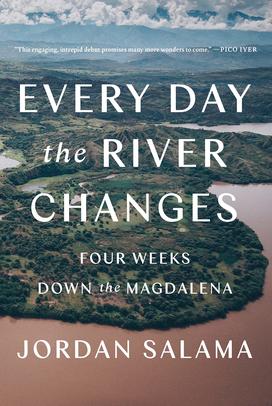

The book: Every Day the River Changes: Four Weeks Down the Magdalena (Catapult) is set deep in the heart of Colombia, where Salama explores the rich history, geography, and culture present up and down the Magdalena River. A rollicking account of his travels, Salama describes the wild and wonderful experiences of his journey including encountering invasive hippos, a jeweler still practicing the art of fine silverwork deep in the jungle, and a library that delivers books via donkey. Travelling from the height of the Andes to the edge of the Caribbean Sea, Salama’s account is at times mournful, inspirational, joyous and somber. He offers a sprawling and gripping account of the people, a river, and a nation.

The author: Jordan Salama ’19 is a journalist, video producer, and writer, with work featured in the New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, and NPR. He has written on a variety of subjects, from a restaurant in his childhood neighborhood, to a traveling Syrian salesman in the Andes. He has an A.B in. Spanish and Portuguese Studies from Princeton, where his thesis, a precursor to Every Day the River Changes, won both the Ricardo Piglia award and the Stanley J. Stein Prize for Best Senior Thesis.

Excerpt:

It was sunset when I saw the boats. I was walking close to the water and stopped, letting the waves lap gently against my feet as I stared out toward the horizon. They did not look like regular boats. They looked like submarines, because you could only see the pointed black tips on either end protruding from the swells of the sea. Every evening, reliably, just before twilight, they would curiously jet across the horizon in a single-file line, and I would watch them. Finally, I thought to ask.

“What are those boats for?” I turned to Vismar and Colo, two boys my age whom I’d befriended in this Pacific beach town of Colombia called Ladrilleros. “Those ones are the fishing boats,” Vismar said. He and Colo cackled, as they often did when they heard my Argentine-accented Spanish with an American tinge or when I asked questions that they thought were strange, like how they knew their way around the labyrinth of backwater mangroves like roads or what went on in the jungle-clad mountains that loomed over our heads. “Why are you laughing?” I asked this time. “We call them fishing boats, but they only fish during the day.” Colo clarified. “At night, they continue north, to bring the cocaine to Central America.” They cackled again, even louder now. My face turned bright red, and I immediately regretted having asked anything at all. It was 2016, my first time in a foreign country alone. I was nineteen, wary and scared. I had been told to ask questions about anything I wanted but never about the cocaine. Never the guerrillas. That’s how you got in trouble in Colombia, people said, by asking too many questions about the wrong things. I guess Vismar and Colo noticed my discomfort. “Don’t worry about it, really,” Colo reassured me, and he was being earnest. “Around here, everything’s calm.” Tranquilo. I nodded. Colo walked ahead and motioned for me to follow. But then Vismar mumbled something under his breath, and Colo stopped. They stood very close to each other and whispered things very quickly and incomprehensibly, as if debating whether to tell me something. “What is it?” I asked nervously. “No, it’s really nothing,” Colo said, and they kept whispering. I did not say anything. Finally, after about a minute, they stopped, and Vismar came over to me. “Well,” he said, “there is one thing we think you should know.” I looked to my left. The boats had sped away, out of view. To my right, lanky waterfalls poured from volcanic outcrops onto the black sand. The air smelled like rain. I suddenly remembered how isolated I was, how far I’d come on the bouncy speedboat from the city. “Tell me.”

“It’s just that . . . well, we have a thief in town,” Vismar confessed. “He’s been stealing from many of the hotels.” I shook my head, somewhat confused. “A thief ’s not all that bad,” I said. “You’re right,” Vismar continued, “but he’s been causing lots of problems for people around here. They told him to stop, he wouldn’t listen. So they hired someone to come from the city to take him out to sea and . . .” He made a gun with his index finger and thumb and then clicked it in his mouth. Suddenly, I preferred the cocaine boats. “Why would they do that?” I asked. “They could have just put him in jail.” “He’ll just get out again and keep stealing,” Colo interrupted. “All of us in this village are poor, we have nothing. He is the only one who steals. That’s not fair.” “Makes sense.” I said it but didn’t mean it, or I hoped I didn’t. “When is this happening?” “Tonight, si Dios quiere,” Vismar said. God willing. “It’s very exciting for all of us. But you shouldn’t even be thinking about it.” All of this was to say that even the biggest problem in town shouldn’t have concerned me, or any of the other beachgoers, and that I was safe.

I was five years old when I started taking piano lessons from a woman named Sandra Marlem Muñoz. The year I was born, she’d moved to New York from the Colombian city of Cali to pursue a career in music. Sandra was in her thirties when I first became her student. She used to come to my house on Tuesdays after school. “Hi, Jordan! How are you?” she would always say in her singsong, accented English. Everything about Sandra was musical. Her heels clacked against the wooden floor; her metal bracelets jangled as she walked. If my dad was home they would speak Spanish, a language that I did not yet fully understand but that sounded like music itself. Hers was a flying staccato, typical of Colombia, my dad’s a slow, more exaggerated Argentine Spanish that sounded almost like Italian. During breaks, Sandra would play songs from her country. The small upright piano in the corner of our living room smiled as it came to life with pulsating, arpeggiated salsas and arabesques. A far cry from the slow drone of my attempts at Beethoven and Bach, her music was pure energy, and it was loud.

“I want to learn those,” I would say to Sandra as she and my mother drank tea after my younger brothers and I were finished with our lessons. “Please, Sandra, I want to play those.” I was a child then, and I did not know many things. I had no idea at the time that a long-running armed conflict had been shaking Colombia to its core—that when most Americans thought of the country in the upper-left corner of South America, they thought of cocaine, of Pablo Escobar and the narcos, and of communist guerrillas hidden away in the jungle. Colombia reminded them of targeted assassinations of soccer players, of air strikes and bombings, and of entire cities and villages paralyzed by war. They thought of the drug-running boats that I was so worried about in Ladrilleros. But Sandra never spoke of these things when we were together; my window onto Colombia was Sandra’s music. Besides soccer tournaments like the World Cup qualifiers and the Copa América— which, as a born-ready Argentina fan, I watched without fail—just about the only time I ever thought of the country was when I was with her. And all I can remember, now looking back, was sitting beside her at the piano each week and watching over the years as my slow scales transformed into the rambling melodies of the songs that I’d so desperately wanted to learn when I was just starting out.

After my first year in college, I was offered the opportunity to see Colombia for myself. It was a chance encounter through the Wildlife Conservation Society, the organization that runs the zoos and aquariums all over New York—these were the stomping grounds of my childhood, when I used to visit with my parents and younger brothers and stare wide-eyed through the Plexiglas at howler monkeys scratching their underbellies and hippopotamuses wallowing in the mud. WCS supports wildlife conservation around the world, announced the signs at the zoo, though I never gave this fact much thought until I was older and actually decided to try to work for them. In school I’d become obsessed with the idea that the survival of those same species in the wild was deeply intertwined with the decisions and destinies of ordinary people, that perhaps my job could entail telling stories illuminating those relationships, in order to help encourage a greener path forward. One day, the WCS office in Colombia called me back. If I wanted to spend a month helping with their communications efforts, based in their office in the city of Cali but traveling around the country, they would have me—the drug violence and guerrilla warfare had been waning for about two years already in the places where I’d be going, they told me, and there were rumors of a peace deal in the works that could end the conflict for good. The official travel policy of Princeton University, which funded my trip, was more cautious. I would have to sign my life away on several waivers, saying that if I died at the hands of drug traffickers or paramilitary militias, the university was free from liability; it soon became clear to me that everyone whom I told I was going to Colombia had similar fears, whether or not they expressed them aloud. This was far from reassuring.

Reviews:

“A mesmerizing travelogue . . . Both complex and achingly beautiful, this outstanding account brims with humanity.” —Publishers Weekly

“Jordan Salama writes with an attentiveness, and a sense of adventure, that many of us might envy; this engaging, intrepid debut promises many more wonders to come. Already he’s shown himself to be a writer with a rare (and inspiring) commitment to giving us the world.” —Pico Iyer, author of Autumn Light

No responses yet