Editor’s note: A previous version of this article misstated which of Julia Ioffe’s relatives was a chemical engineer. It was her grandmother. Also, Vladimir Lenin’s wife was misidentified. Her name was Nadezhda Krupskaya.

Recipients of work emails from Julia Ioffe ’05 often are treated to her signature signoff: “Tomorrow will be worse.”

Ioffe, the chief Washington correspondent for the online news media website Puck, started using that bleak coda during the summer of 2016, when the world seemed to be spinning out of control. There was the daily Trump-Clinton campaign circus, WikiLeaks, peak Twitter outrage, and a mass shooting in Dallas. At the end of one particularly crazy day, she checked out with, “I’m going to bed. Tomorrow will be worse.” She liked the line and kept using it.

Over the last nine years, history has largely proved her right.

And so, Ioffe has embraced it. Back in 2021, she even wanted to use it as the name of her Puck newsletter. Not surprisingly, potential advertisers weren’t keen on being associated with such a bummer title, so Ioffe changed it to the more upbeat, “The Best and the Brightest.” Her not-so-subtle allusion to David Halberstam’s history of America’s descent into the Vietnam quagmire slid under the corporate radar.

“Tomorrow will be worse.” That view of the universe puts Ioffe among a distinguished company of pessimists, from Arthur Schopenhauer to H.L. Mencken, not to mention Eeyore. But in Ioffe’s case, as many have noted, it is also a particularly Russian take. Though she writes on a broad range of topics, Ioffe is best known as a writer about Russia. She lived in the former Soviet Union until the age of 7 and returned to the country many times as a journalist. Whenever Russia is in the news, which these days is nearly always, Ioffe becomes the mainstream media’s go-to expert.

“She understands Russia in a visceral way,” says New York Times correspondent Peter Baker. “She can explain us to them and them to us in a way no other reporter can.”

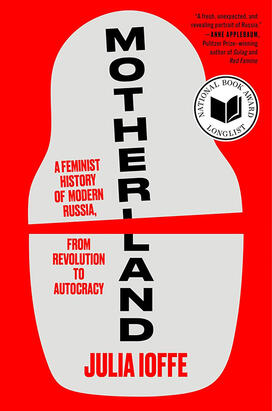

In her new book, Motherland, A Feminist History of Modern Russia, From Revolution to Autocracy (Ecco), Ioffe seeks to explain them to us through a new set of lenses. She traces Russia’s tortured history over the last century — from czardom to Bolshevism to Communism to oligarchy and back to authoritarianism — focusing on the lives of its women. Chapters are centered around Russia’s first ladies, from Nadezhda Krupskaya, Vladimir Lenin's wife, to Lyuda Putin, most of whom have remained in history’s shadows. Through that public record, Ioffe weaves her own matriarchal line, tracing the lives of her great-grandmothers, grandmothers, mother, and even herself. Motherland, which will be released on Oct. 21, has already been named to the National Book Foundation’s longlist for nonfiction book of the year.

Buried amid generations of Russian privation is a question about the role of women that Ioffe seeks to answer. For several decades after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, Russian women had rights unknown throughout most of the Western world: equal access to education, equal pay in the workplace, and paid maternity leave. Soviet women served as fighter pilots during World War II and as cosmonauts at the dawn of the Space Age. Of Ioffe’s great-grandmothers, two were doctors and one was a Ph.D. in chemistry.

Much of that progress was already coming undone before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. President Vladimir Putin and a revitalized Russian Orthodox Church have almost completely erased it. Her book is an attempt to understand how it happened.

“There have been many books on post-Soviet, Putin-era Russia, but Julia goes at her subject from a rare point of view and, for an American, with the advantages of having a rich émigré background and superb Russian and feel for Russianness,” writes New Yorker editor David Remnick ’81 in an email to PAW. “It’s a profoundly interesting and soulful book.” Remnick has also written extensively about post-Soviet Russia, including the 1994 Pulitzer Prize-winning Lenin’s Tomb.

“This is a book I wish we had when we were correspondents there,” adds Susan Glasser, who hired Ioffe to write for Foreign Policy in 2012.

Motherland is a depressing story, because Russian history is depressing. But as Ioffe covers current affairs, she has grown increasingly alarmed about the future in this country, too. In Russia, tomorrow is almost always worse. But now, Ioffe warns, that forecast could be America’s.

Although Ioffe is always in demand, on certain weeks, such as the one in mid-August when President Donald Trump met Putin for a mini summit in Alaska, it ramps to higher levels.

In addition to her columns and subscriber newsletters for Puck, Ioffe is a regular on CNN, MSNBC, and PBS, and a frequent guest of late-night talk show hosts. Often, she shuttles between her home in Northern Virginia and various TV studios, though networks will sometimes send a broadcast truck to her house, enabling her to film segments remotely. Like most current journalists, Ioffe is active on social media and has occasionally gotten into trouble for being a little too hard-edged. Lately, she has also been in the studio recording the audiobook of Motherland and caring for an infant at home.

Amid all this, Ioffe spends part of each day “pounding the virtual pavement,” trying to do reporting. Keeping up with her many sources in Russia has gotten harder as the government has cracked down on communications apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram. (Keeping up with sources in the federal bureaucracy here has gotten harder because no one is willing to talk anymore, she adds.) Ioffe has not been back to Russia in several years, as the Putin regime has made it more dangerous for all journalists, especially Russian ones. The Soviet Union stripped her family of their citizenship when they left, and although Ioffe says that the government has offered to restore it, she is wary of doing anything that could make her subject to Russian jurisdiction.

Journalistic careers are peripatetic, but over the last two decades, Ioffe seems to have worked everywhere: The New Yorker, The New Republic, Politico, The New York Times, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, GQ, and elsewhere. She has been at Puck since its founding in 2021.

Born Yuliya Ioffe in Moscow, she and her parents, a doctor and a computer programmer, left in 1990, a month before she was to finish first grade. The Ioffes settled in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., determined to become Americanized. Ioffe says her mother, who is fluent in three languages, rarely speaks to her in Russian anymore.

“My parents very purposely tried to stay out of the émigré communities,” Ioffe says, “because they were moving forward.” They were also Soviet Jews, and although Ioffe says she is not observant, she takes her Jewishness “very seriously.” Asked whether she thinks of herself as Russian, American, or Jewish, Ioffe answers simply, “Yes.”

“When I was little, there was a lot of pressure, both internal and external, to pick one,” she recounts. “As I got older, I realized that not only is it impossible, it’s also inadvisable. I have all these different lenses to see the world.”

In 2001, Ioffe entered Princeton intending to follow her mother’s footsteps into medicine. Instead, she majored in history, with a certificate in Russian studies. Although her parents had Americanized, they had also made sure that Ioffe would know about her Russian ancestry. In Motherland, she shares a vivid memory of the day in high school when her mother read aloud a poem by Soviet poet Anna Akhmatova called “Requiem.”

And if they squeeze shut my tortured mouth,

Through which one hundred million people scream,

Let them remember me thus

On the eve of my remembrance day.

Horrifying as that legacy was, Ioffe recognized that her mother was passing it on to her, “the rightful inheritance of any child born in the Soviet Union: the pain of what our history did to all of us, and the obligation to feel it.”

The Princeton faculty member who enabled Ioffe to feel that history was emeritus professor Stephen Kotkin, whose course called The Soviet Empire she took as a sophomore. It was a famously demanding course, she recalls, but Ioffe would sit in the front row and soak up Kotkin’s lectures. She also impressed Kotkin, now a senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, who has followed Ioffe’s work since she left Princeton.

“She was a dynamo,” Kotkin recalls, “very passionate and full of energy, but energy directed toward understanding and making better the place where she came from.”

Ioffe returned to Russia on a Fulbright scholarship in 2009, spending the next three years there as a contributor for The New Yorker and Foreign Policy. It was a pivotal time in modern Russian history. After nominally stepping down as president in 2008, Putin returned to power in 2012 and quickly consolidated it, snuffing out all opposition. Ioffe covered the flickering resistance, such as the feminist punk rock group Pussy Riot. Her profile of opposition leaders Alexei and Yulia Navalny in 2011 won a Livingston Award, given by the University of Michigan to journalists under age 35.

Remnick recalls working with Ioffe during her time in Moscow. Once, they both interviewed Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, and afterward attended a dinner Ioffe had organized. “That dinner made crystal clear to me that Julia was wired into a new generation of Russians (many of them the sons and daughters of Soviet-era dissidents) that I didn’t know nearly well enough,” Remnick writes. “Her fluidity with them — linguistic, personal, journalistic — was something to see.”

Returning to the U.S., Ioffe wrote about American politics for several publications, but Russia kept calling. In 2021, she became one of the co-founders of Puck, as well as its chief Washington correspondent. Puck has a relatively small subscribership of about 40,000, but Ioffe says it’s the right audience, composed of movers and shakers in news media, entertainment, finance, tech, and government. (A 2022 New Yorker profile of Puck called it “the email newsletter for the mogul set.”) “You need to read us to know what’s going on,” boasts Ioffe, who says she has heard that members of the CIA sometimes read her for inside scoops.

Motherland, Ioffe’s first book, evolved over several years. She wanted to explain Russia to Americans “because I was sick of doing it on TV over and over and over again,” she said in an Aug. 8 Instagram video. Her working title was Russia Girl, Ioffe’s nickname at many of the newsrooms she has worked in because of her expertise.

A sample chapter of Russia Girl, which she pitched to publishers, traced the history of Russian women, including the women in her own family. That’s your book, they told her. As she came to realize, though, to tell that personal story in context, she also had to explain Russian history over the last century.

Not to name drop, but Ioffe says her friend Nina Khrushcheva *98, granddaughter of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, suggested the title, Motherland, and the focus on the wives of Russian leaders. Chapters also explore figures unknown to most Americans, such as Alexandra Kollontai, one of the chief Bolshevik political theorists, and Lyudmila Pavlichenko, the top Soviet sniper during World War II, with 309 recorded kills. But in Russia particularly, public history is also personal.

Although her immediate family was largely spared from Nazi terror during World War II, Ioffe tells their stories with brutal poignancy. She writes that her paternal grandmother, Khinya Tartakovskaya, fled her town in Ukraine on July 4, 1941. By July 9, escape routes had been closed and within weeks, more than 10,000 Jews in the area had been killed, including 11 of Khinya’s dozen cousins. Miraculously, Khinya got out.

“Five more days of trying to guess which move was safest — an impossible algorithm in the summer of 1941 — and my grandmother would have been killed around the time of her thirteenth birthday,” Ioffe writes. “Five days are why I exist in the world today.”

The loss of millions of men during World War II distorts Russia to this day, Ioffe believes. Khruschev and subsequent Soviet and Russian leaders placed a premium on upping the birthrate, but because there were not enough men to go around, single motherhood became commonplace. Russian women worked full time and did most of the domestic housework, as well — the Western “second shift” on steroids. Increasingly marginalized in a stagnant economy and by their own irrelevance at home, men turned to drinking, violence, and other destructive behavior.

Once he returned to power, Putin promised a return to traditional morality known as skrepy or “spiritual bindings” that define Russian society. Accompanying it were escalating crackdowns on independent speech, news outlets, and art. Feminism was dismissed as an alien, Western, anti-Russian contagion.

One skrepy was the traditional male role as head of the household, a role few Russian men are able to hold. “Several generations after World War II, there was still a sense, bordering on panic, that good men — the ones with well-paying jobs and without drinking problems — were essentially an endangered species,” Ioffe writes. That helps explains one of the curiosities of Ioffe’s book, Putin’s enduring popularity among Russian women. Women are attracted to the Russian leader, she argues, because he is “the man they never had.”

Having witnessed firsthand the rise of authoritarianism in Russia, Ioffe is unnerved by what she sees happening in the U.S.

The symptoms she identifies have been pointed out by many: a supine Congress and a pliant Supreme Court; politicized intelligence, military, and law enforcement agencies; and prizing loyalty to an individual over fidelity to the rule of law. On Aug. 22, Ioffe posted on her X account, “I’m old enough to remember American commentators asking, every time Putin did anything increasingly authoritarian, why Russians weren’t out in the street protesting and toppling the dictatorial regime. Wondering what they’re thinking now — and why they’re not asking that about Americans.”

Civic institutions die gradually. “It’s never all at once,” Ioffe warns about a country’s slide into authoritarianism. “You create an emergency; you seize an opportunity.” She points to a number of recent events, such as stationing troops in U.S. cities during peacetime, or deporting people to foreign prisons without a hearing, that would have been inconceivable a decade ago but are now part of our civic discussion. In a meeting with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on Aug. 18, Trump even joked — perhaps — that war could provide a pretext to suspend U.S. elections. “Three and a half years from now, if we happen to be in a war with somebody, no more elections,” the U.S. president said to a foreign leader. “Oh, that’s good.”

“Hahaha, right?” Ioffe responds. “It’s always, ‘Oh, hahaha.’ But they’re all trial balloons.”

Perhaps a better label for her would be the one John F. Kennedy gave himself, an idealist without illusions. Her job, she believes, is “to bear witness and speak the truth as I see it. And not be afraid.”

“What’s so hard for me about this moment,” Ioffe says, “is that before, in Russia, when I had this feeling, I still had my blue American passport. I could go home.” Home no longer seems like the place it was.

Still, “pessimist” seems too bleak a word, and too passive, to describe someone who championed Navalny and Pussy Riot, who made the Putin resistance beat her own. Ioffe also rejects that label, saying that she adopted the line “Tomorrow will be worse” as a sort of “f--- you” to Americans “who need every story to have a happy ending and need to believe that the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice.” Sometimes it does, but read your history, especially Russian history. Sometimes it doesn’t.

The way to ensure that it doesn’t is to look away. In Russia, Ioffe notes, there is a concept known as internal immigration. It is not physical but emotional relocation. Rather than resist, people tune out. Political change is impossible, they conclude, so they turn inward to focus on the nonpolitical things in life that make them happy.

“I don’t think we’re quite there yet, but I feel myself being pulled in that direction,” Ioffe says. “Americans still have elections. We do still have a free media. We can still do things. But it’s all really scary.”

Ioffe is not resigned to that fate. Perhaps a better label for her would be the one John F. Kennedy gave himself, an idealist without illusions. Her job, she believes, is “to bear witness and speak the truth as I see it. And not be afraid.”

Of course, she brings it back to Russian history. Many of those killed under Stalin, Ioffe notes, first tried to compromise. They signed false confessions when they were brought in, hoping that it would buy them leniency. Stalin killed them anyway.

“You only die once,” she says of those who bend the knee, “but your reputation, your morality, and your moral compass have to remain intact. Those will live on long after you’re dead.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

2 Responses

Walter M. Weber ’81

1 Month AgoAuthoritarianism For Me But Not For Thee?

Again we read in PAW about someone’s concern with “the rise of authoritarianism” in America (“Tomorrow Will Be Worse,” October issue). Of course we should be concerned about the tendency of the executive branch to aggrandize its power and to use it selectively against political opponents. But I don’t recall seeing anything — anything at all — in PAW about the Obama administration slow walking and denying the 501(c)(3) tax exemptions for politically disfavored groups; or the Biden administration deploying the Department of Justice and the FBI against politically disfavored targets (like pro-lifers, parents objecting at school board meetings, January 6 protesters, and “traditional” Catholics) while largely disregarding political allies, even when violent; or the Biden administration coordinating with Big Tech to suppress online messages that crossed the official narrative.

Of course, PAW could (and maybe should) steer clear of all these subjects as having little to do with Princeton, even though there are doubtless Tiger players involved or commenting. But to platform jitters about Trump, while ignoring overreach by Democrat administrations, could lead a reader to wonder if what is at issue here is not so much genuine concern about the power of a president as, rather, partisan objection to how that power is being used.

Bailey Stone *73

4 Months AgoNew Book on Women in European Revolutions

I am responding to your fascinating article with some comments that you might find relevant. I did my Ph.D. work from 1968-73 at Princeton under Robert Darnton, Lawrence Stone (no relation!), David Bien, Arno Mayer, et al. I then served as instructor in history at Princeton during the period 1972-75, before leaving for the University of Houston.

I write, in particular, because I have already suggested that Bloomsbury Academic, which is about to publish my 7th and latest book, Women in the Great European Revolutions: Gender, Culture, Class, and the State, send PAW a copy. My latest study is a grand synthesis that delves into the status, mentalities, and destinies of women — from tsarinas and queens to workers and peasants — who lived during Europe’s three classic revolutions: the English “Puritan Revolution” of 1640-60, the 1789 French Revolution, and the 1917 Russian Revolution — or, better yet, Revolutions. The book also endeavors to update the huge and important literature that deals with the theorizing of gender, sexuality, and patriarchy in the specific historical contexts of such transformative sociopolitical upheavals, in and beyond Europe.

I hope that PAW’s editors and your many readers will find these comments of some interest. The book is due to appear, here and internationally, over the next two weeks.