Ledio Cakaj *09: Refugee To Researcher

Displaced at 16, an Albanian refugee brings a new perspective to the plight of child soldiers

Ledio Cakaj *09’s hardscrabble youth — escaping communist Albania as a teen after multiple attempts and living illegally in several European countries — provided some insight during his years of field research on guerilla groups that use child soldiers. In the Albania of his youth, he says, “some of my friends turned to weapons. It was not nearly the same as in Burundi or Uganda, but I wasn’t completely unaware.”

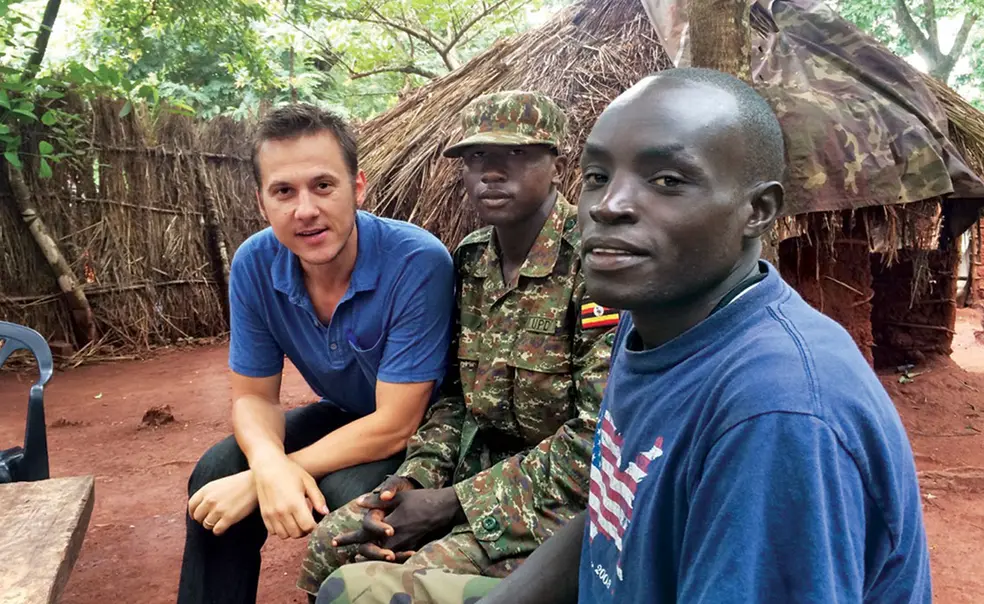

Cakaj’s recent book, When the Walking Defeats You: One Man’s Journey as Joseph Kony’s Bodyguard (Zed Books), is the culmination of his years of research on the brutal, three-decades-long battle waged by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in eastern Africa. The plight of his subjects resonated for the former refugee. George Omona, the book’s main character, had harbored dreams of going to college and becoming a teacher. Instead, after being expelled one term before graduating from high school, he became a bodyguard for Joseph Kony, the messianic leader of the LRA. “George’s journey and mine were not the same, but there were some parallels,” Cakaj says in an interview in Washington, D.C., where he resides with his wife, human-rights lawyer Maria Burnett ’98.

Cakaj was born in 1978, at a time when Albania was one of the most isolated countries in the world — “it’s been compared to North Korea today,” he says. The United States was the enemy, and capitalism was evil. In 1991, when Cakaj was 13, the country began to collapse. The communist dictatorship was bad, but the situation after it fell was in some ways worse. His parents lost their jobs, the family struggled financially, and going to school seemed pointless. Soon, media images of Western affluence flooded in, highlighting how deprived Albanians’ lives really were. Many Albanians decided to leave. Cakaj began trying to do that in 1994.

After several increasingly dangerous attempts, his parents hired a guide who was able to get him into Greece. It was 1995, and Cakaj was not yet 17. He found jobs waiting tables and as a day laborer, but one thing was always out of reach: “I couldn’t go to school,” he says. “I was an illegal immigrant, and the Greeks were fed up with us.”

Seeing no future in Greece, Cakaj moved on: next to Italy, then to France, and finally, in 1999, to England. He got a break when an English woman he met on a train took him in, rent-free, after hearing his story. Staying in her home allowed him to apply for asylum, study English (something that gave him “massive headaches”), and return to high school at age 21. Eventually he received a student visa and matriculated at Oxford; by 2005, he had earned a degree in ancient and modern history.

After graduation, Cakaj moved with Burnett to Burundi, a country that had only recently transitioned out of civil war, and took a job with a contractor for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Two years later, he was accepted into the Woodrow Wilson School, and he earned an M.P.A. in 2009. Building on his experiences in Burundi, Cakaj did extensive field research in Uganda, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, focusing on Kony and his army, including their tactic of forcing children into service, sometimes after killing their parents.

Cakaj’s research has convinced him that it’s wrong to think of rebels like those in the LRA as being “evil, irrational, and impossible to engage. They are humans, and there’s a reason why things have gotten to that point.” Kony is estimated to have fewer than 100 armed men, but “as small as they are, sometimes they offer the only option for status in a bleak environment,” he says. The lesson Cakaj has drawn from hundreds of interviews is that soldiers “commit terrible crimes because they’re afraid and hungry, not because of ideological conviction. For them, it’s literally a fight for survival.” Eventual reintegration in society is possible, but it’s complicated and “a lifelong process,” he says.

Cakaj goes back to Albania periodically (conditions are “much improved,” he says), and both of his parents were able to visit him in the United States. In 2014, he became an American citizen. “I was somehow lucky to get this golden ticket,” he says. “It was an extremely important moment for me, as someone whose idea of identity and documentation has been so convoluted.” He adds that being a citizen feels especially poignant now, at a time when the country seems to be closing itself off from the world. “I find it disturbing that this country is shutting doors,” he says. “[It] closes options for people with dreams, creates more desperation, and [creates] more fertile ground for radicalization.”

No responses yet