Leonard Milberg ’53 Helps Return 16th-Century Texts to Rightful Home

Leonard Milberg ’53, a passionate collector of art, rare books, and manuscripts, loves a rare find — especially those related to Jewish or Irish life and literature. And so, in 2016, when he spotted a listing in an auction catalog for three autobiographical and religious manuscripts by Luis de Carvajal the Younger — who was executed in 1596 for secretly practicing Judaism in Mexico during the Inquisition — Milberg immediately arranged to see them.

The 16th-century manuscripts would not end up in Milberg’s collection, however. In researching them, he discovered that they had been stolen from the Mexican national archive in 1932. Milberg helped the Mexican government reclaim them, and in August, he received that government’s highest award for foreigners, the Mexican Order of the Aztec Eagle.

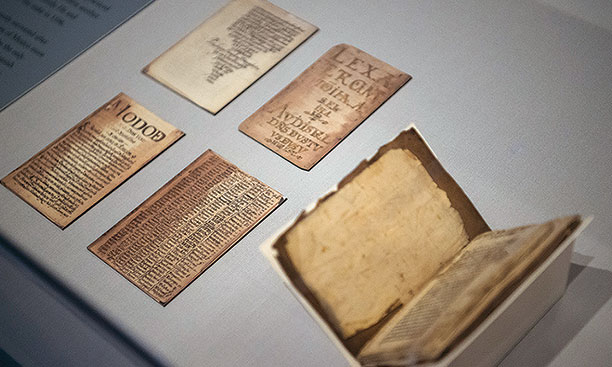

De Carvajal’s manuscripts comprise three documents totaling 180 pages, tiny enough to fit in the palm of a hand (likely for discretion’s sake), written in Latin and Spanish in diminutive script and stitched together. The documents are believed to be the only existing writings from a Jew in Mexico during the Spanish colonial period; together they “contain a giant-sized tale of one family’s devotion to Judaism despite their separation across generations and continents from other Jews,” Milberg wrote in an article for the Princeton University Library Chronicle.

One document was a copy, written by de Carvajal and illuminated with gold, of the Ten Commandments and the Thirteen Principles of Faith by the great Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides. Another, also written by de Carvajal, was a prayer manual. The third was de Carvajal’s autobiography, which details how he lived publicly as Catholic but secretly worshipped as a Jew. It includes stories meant to highlight his devotion, such as his self-circumcision and his successful entreaties to bring his siblings into the faith.

The memoir was begun while de Carvajal was imprisoned and completed during a temporary release. Arrested again in 1596, under torture he revealed the names of more than 120 Jews, before being burned alive with family members.

Though the booklets had been listed by Swann Auction Galleries as very old copies — not the manuscripts written by de Carvajal himself — Milberg was convinced they were original. “I said, ‘This is not a copy.’ It had gold leafing on it. Who would put gold leafing on a copy?” he says. He brought in experts, at his own expense, to authenticate the documents; when the manuscripts were found to be de Carvajal’s, the sale was canceled and the FBI brought in.

Milberg was pleased that the writings would be returned to Mexico’s archives, but he lamented that “undoubtedly the most important and oldest Jewish manuscripts of the New World” would not be exhibited. He worked with the Mexican government to allow them to be shown at a 2016 exhibition at the New-York Historical Society and to have digital copies made for the city’s Spanish-Portuguese synagogue, the historical society, and Princeton.

Milberg became interested in art during his Army service, when he filled some of his free time reading books about art. Over the last four decades, he has donated several collections to the Princeton University Library: drawings and watercolors; American poetry; prints; Irish poetry, prose, and theater; and works by Jewish American writers. “I follow my curiosity,” says Milberg, who especially relishes finding unpublished manuscripts by noted authors. Milberg “reads voraciously, and that reading points him to figures who are understudied or obscure,” says English professor Esther Schor, who has used the collection on Jewish American writers in her research and courses.

Milberg’s latest find — the de Carvajal manuscripts — is a reminder that Jews came to the New World more than 400 years ago and made significant contributions. “There is something beautiful and moving when you have something that’s in the hand of an author,” Milberg says. “It’s as if you’re communicating directly with the writer.”

No responses yet