Several years ago, when Jennifer Baszile *99 was thinking about writing a memoir of her childhood, her mother advised against it. Picking apart the struggles she faced as an African-American growing up in a predominantly white, affluent community in California “will take you under,” her mother said at the time.

The warning didn’t stop her. But her mother was right that the process of mining her childhood — which was marked by the sting of prejudice and isolation — would not be easy.

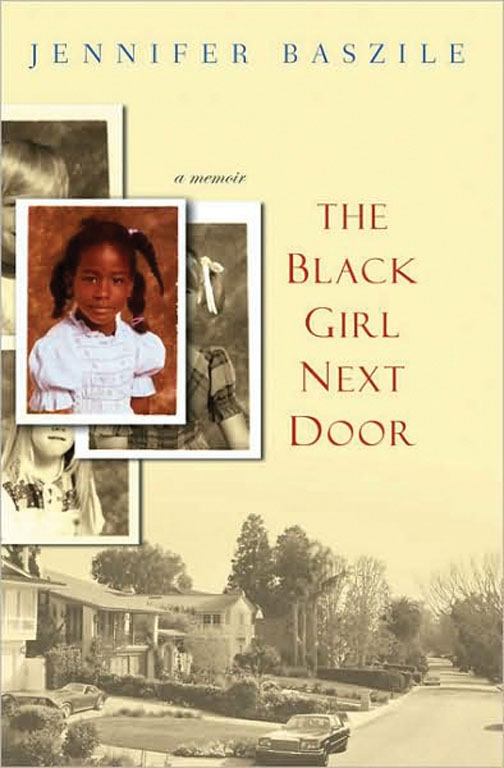

Baszile, 39, says she wrote The Black Girl Next Door, published this month by Touchstone, to express what it meant to live in the generation raised after lunch counters were desegregated. As an assistant professor of history and African-American studies at Yale, she couldn’t teach her students effectively about the “sinews and tendons” of the history of race in America without coming to terms with her personal history of integration, she says. At first she looked for memoirs by blacks of her generation. But she came up empty-handed. No one was talking about “this pivotal moment in American life when black and white kids had to actually grow up together” — in classrooms, neighborhoods, around dinner tables, and on playing fields — “when integration was made real,” says Baszile, who earned her Ph.D. in American history at Princeton and became the first black female professor to join Yale’s history department.

In The Black Girl Next Door, Baszile recounts defining moments in her childhood. Soon after her parents had moved the family from a predominantly black neighborhood in Carson, Calif., to Palos Verdes, Calif., teenagers spray-painted profanities on the sidewalk in front of their new house. In second grade, three white boys attacked her on the school playground, while other kids gathered around to watch the fight. And in fourth grade, her teacher stammered through a lesson on slavery: “I guessed that she had never taught the subject of slavery in the presence of a black student,” wrote Baszile. “That day I had felt my classmates’ eyes on me. ... It felt like they were trying to find the slave in me.”

Through these stories, Baszile touches on the exhaustion that comes from striving for the American dream and the toll that her parents’ drive for “upward mobility” took on the family.

She tells her story — which ends with her high school graduation and her eagerness to head east for Columbia University — “warts and all.” She delves into her complicated relationship with her father, a successful business owner, who was strict and demanding, climaxing in a painful chapter about an incident in which he bullies her and she fights back. “I don’t think he realized that my California girlhood had instilled as much rage in me as his Louisiana boyhood had instilled in him,” she writes.

As a child, she tried to make sense of her parents’ reluctance to speak about their own pasts and visit their families. Her father, for example, grew up in the segregated South and it was only two years ago that he told her about indignities — including violence — he endured. Her father never told her those stories as a child, she says she realizes now, because a parent can’t tell his children about his mistreatment and then expect them to go off to school and make friends with white kids.

The Black Girl Next Door

No responses yet