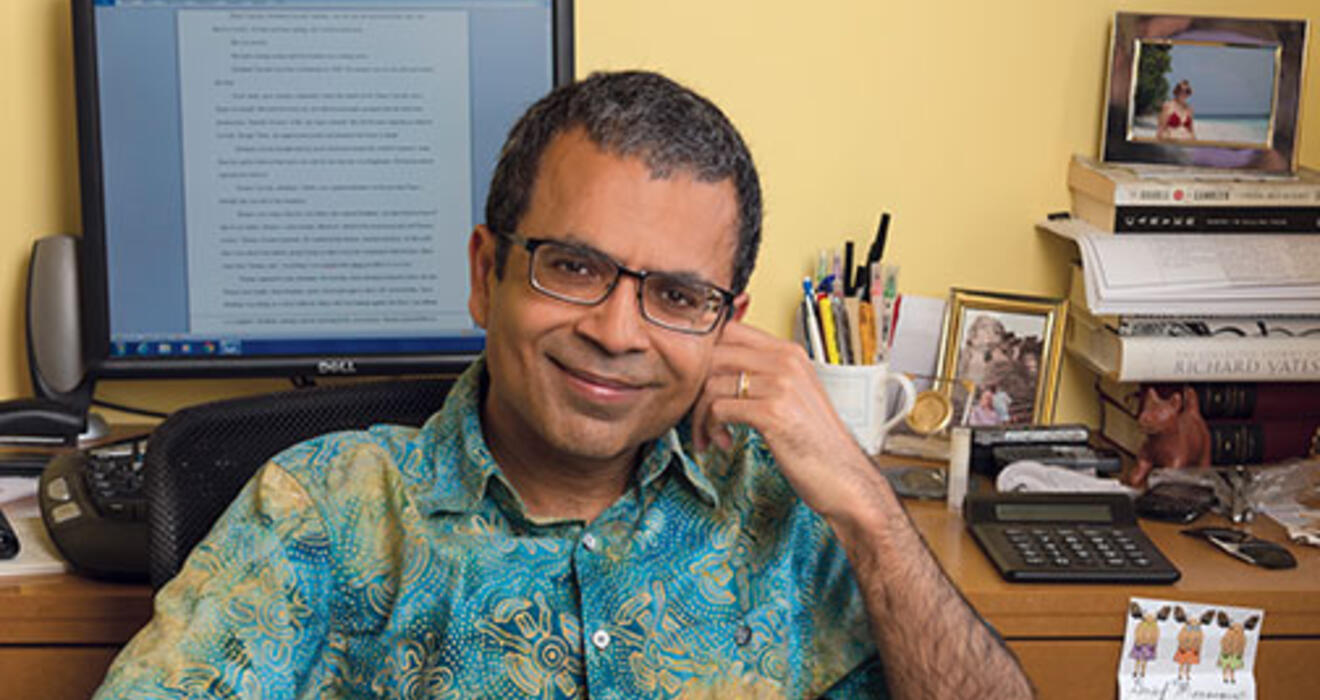

At the age of 8, novelist Akhil Sharma ’92 and his family emigrated to the borough of Queens in New York City from Delhi, India, where they lived in two cement rooms on the roof of a house and saved the cotton from pill bottles for re-use. Living in America was like a dream: There was orange juice; there was hot water whenever you turned on the tap. His parents had moved in search of academic and economic success for their two sons — his father, an accountant in India, worked as a clerk in New York — and they soon were rewarded: Sharma’s older brother, Anup, was accepted to the elite Bronx High School of Science. But one summer day, when Sharma was 10 and his brother 14, Anup dove into a swimming pool and struck his head on the bottom. He remained underwater for three minutes; when he was pulled out, he had catastrophic brain damage that left him blind and unable to communicate or move.

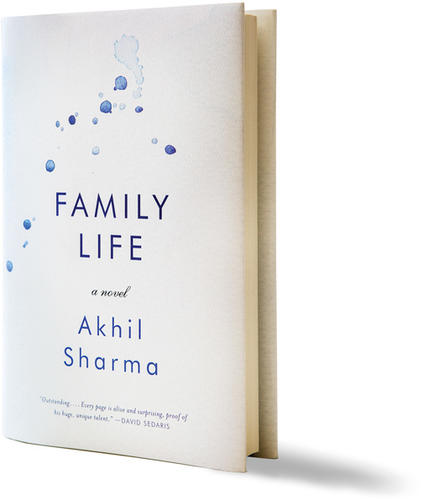

How the family’s life was shattered — and the pain and rage of the many years during which they cared for Anup at home — is captured in spare, heart-wrenching prose in Sharma’s autobiographical novel Family Life, which was named one of 2014’s best books by The New York Times and other publications. Yet when the book was selected in March as the winner of Britain’s Folio Prize for fiction — which comes with 40,000 pounds (about $62,000) — the first emotion Sharma felt was shame.

“I felt like I’ve always been the lucky one,” he says.

Turning such a painful story into a novel was anything but easy. Sharma spent 12 1/2 years on the book, writing more than 7,000 pages — not revising, but starting each new draft with a blank page — before producing a slim novel that offers a darkly funny, unvarnished portrait of one family’s deterioration.

Writing the book “was like chewing stones,” says Sharma, who worked on Family Life from age 30 to 43, burning through three computers and two Aeron desk chairs. “I wish I had not started the book. I wish I had not been the schmuck who wrote it. I feel like I shattered my youth against it.” But, he says, there were “all these things I felt I had to honor.”

Sharma is a rising star in the fiction world; he made Granta’s list of best young American novelists in 2007 and had won two major awards by the age of 30. As an undergraduate at Princeton, he took writing courses with professors Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates and did a creative-writing thesis, but he majored in the Woodrow Wilson School. He received a writing fellowship to Stanford after graduation but soon returned East to attend law school at Harvard and begin work as an investment banker. “I just wanted to earn a living,” Sharma says, speaking in a slow, deliberate cadence. Despite the grueling hours, he continued writing fiction in the little spare time he had, and quit banking after his first novel — which began as one of the short stories that made up his Princeton thesis — was published in 2000, when he was 28. That book, An Obedient Father, is about a corrupt Indian civil servant who molests his daughter and granddaughter and feels guilty about it — “less evil than weak,” a New York Times reviewer wrote. The novel won both the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction and the Whiting Writers’ Award.

Almost everything that takes place in Family Life happened to Sharma’s family. “I grew up with a very guilty conscience,” he says, explaining how he felt about living a normal boy’s life in Edison, N.J. — home to a large Indian community — while Anup would lie in bed for the rest of his life. After Anup spent two years in the hospital, Sharma’s parents brought him home, undertaking a grueling regimen of bathing and feeding him that in Family Life consumes all the mother’s love and energy. Though there is no hope of a cure, she invites all manner of faith healers to the house, as Sharma’s own mother did. In the novel, she says, “What kind of mother would I be if I don’t try?” (Sharma has said that while he has “great sympathy” for his mother, “I also feel that [her] doing this created hurt for me and my father.”) Sharma’s brother died in 2012, 30 years after his accident.

The father in the novel descends into alcoholism; in real life, Sharma’s father was depressed, not alcoholic. When the younger son in the book — Ajay, a stand-in for Sharma — says, “Daddy, I am so sad,” the father replies, “You’re sad? ... I want to hang myself every day.”

Fleeing the rage and sadness of his household, Ajay loses himself in books. When he reads a biography of Hemingway, he decides he wants to be a writer because Hemingway was able to travel to Europe “without being a doctor or an engineer.” The boy sets out to write a story. “I had in the past written stories for English classes. These had all been about white people because white people’s stories seemed to matter more.” Ajay’s story is about his brother.

Family Life conveys how the family’s status in the Indian community is elevated by their son’s condition. Parents bring their children to be blessed by the mother before they take their SATs because someone who is suffering is seen as holy. And the novel delineates the way the immigrant experience affects their lives: “My classes had mostly Jews, a few Chinese, and one or two Indians,” young Ajay thinks. “The Indians were not Indian the way I was. They didn’t have accents. They were invited to birthday parties by white children.”

Sharma chose to write the story as a work of fiction instead of a memoir, he told radio host Diane Rehm, because “a part of me is afraid of sympathy. You know, a part of me feels that I’m not deserving of it. And by writing a novel, it’s a way of creating something formal and asking to be judged based on those formal constraints, the constraints of fiction, and so not relying on the power of the subject matter to affect the reader.”

But he left out of the novel one of the most important aspects of his youth: the “gravitational pull” of the “constant despair of living with someone ill, of having no hope,” he told novelist Mohsin Hamid ’93 in a conversation published in the literary magazine Guernica. Despair is boring, he explained, and it kills a reader’s interest.

Sharma is hailed as a writer of immigrant fiction, but the label is too simplistic, he suggests. While Family Life deals specifically with the Indian immigrant experience, it’s really about a child and a family. “To me, these categories don’t make much sense,” he says. “These are just human beings having their experience.” Sharma wants to create fiction that captures life so fully that it “erases the edges of the painting,” he says. “When I write, my intention is to overwhelm, to put everything I have into this story, to not take shortcuts, to try to create something that is great. Nothing else involves us telling each other the most meaningful things.”

The book took so long to write, he says in an essay for The New Yorker, because of the challenge of writing from a child’s point of view and the difficulty in holding a reader’s interest while describing a devastating physical condition. And there was the misery of having to relive excruciating events, which shook his confidence. “I would often meditate on the horrible possibility that my brother might have been aware and not unconscious during the minutes underwater — poor boy, lying on the bottom of the pool and looking up at the people swimming back and forth above him like they were stroking their way across the sky,” he wrote. Even now, “I am not sure if it [writing the book] was the right investment of my time.”

Today, Sharma tries to be disciplined about spending five hours a day writing in his apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side, where he lives with his wife, Lisa. He records how many hours he writes — at the moment he is working on short stories — in a ledger. Twice a week he takes the train to Newark, where he is an assistant professor of English at the Rutgers University campus there. He teaches creative writing to graduate students, but the classes where he feels he truly makes a difference are his undergraduate literature courses.

English is not the first language of many of the students, and most are taking the class because it is required. Some go to the library and photograph every page of the assigned novels rather than buy them — to save money, he says. Sharma hopes to “give students the sense that if they can read deeply, they can think well.” He also wants them to know that they matter. “By giving them attention, I want them to feel that they are deserving of attention.”

Sharma sees a lot of himself in the students. “These are my relatives; they are me. I just lucked out.” Though most would view Sharma as unlucky because of his brother’s accident, he sees himself differently: “Every good thing I did got magnified. It was like I put in a quarter and life gave me a hundred dollars. I was born in a slightly wealthier family. My parents ended up moving to a school system that was good. One piece of luck came after another.”

Jennifer Altmann is an associate editor at PAW.

In this excerpt from Family Life by Akhil Sharma ’92, the narrator, Ajay, discusses his older brother, Birju:

Whenever I told someone about Birju, I felt compelled to lie about his wonderfulness. Because we had received so little money in the settlement, which meant that Birju was an ordinary boy, lying seemed the only way to explain that what had happened to him was awful, was the worst thing in the world. Birju, I said, had rescued a woman trapped in a burning car. Birju had had a great talent for music and a photographic memory.

Sometimes I didn’t tell these lies, but only imagined them. I concocted an ideal brother. I took the fact that Birju had told our parents that I was being bullied and turned this into him being a karate expert who had protected me by beating up various boys. These fantasies felt real. They excited me. They made me love Birju and when I was in his room kiss his hands and cheeks. They also cultivated rage at the loss, the way my father’s claims of racism cultivated it for him.

A part of me was anxious about the lies I told. I was afraid of being caught or doubted. Also, making up these stories seemed to serve as evidence that Birju had not been good enough for what happened to him to count as terrible. Each morning I woke on the sofa thinking of the lies I had told.

Sharma’s interview with the NPR host

No responses yet