Philanthropy, to the Rescue

Having donated more than $19 billion since 2019, MacKenzie Scott ’92 is setting a new model for philanthropy, not just in the scope, but also in the way she gives

In 2019, as MacKenzie Scott ’92 began giving away billions of dollars at a pace that few, if any, in the history of philanthropy have ever matched, her mind traveled back to when she was pinching pennies at Princeton. At the time, juggling jobs with classes wasn’t making ends meet. She tried gluing a broken tooth by herself because she couldn’t afford a dentist. She was on the verge of quitting college as a sophomore for lack of funds.

Nearly three decades after graduation, when circumstances positioned her to be able to give like a Carnegie, Rockefeller, Buffett, or Gates, she didn’t model her singular philanthropic style on such eminent givers.

“Whose generosity did I think of when I made every one of the hundreds of gifts I’ve given so far?” Scott wrote in a 2021 essay on philanthropy. “It was the local dentist who offered me free dental work when he saw me securing a broken tooth with denture glue in college. It was the college roommate who found me crying and acted on her urge to loan me a thousand dollars to keep me from having to drop out sophomore year.”

The acts of charity she experienced at Princeton taught her that the size of a gift matters less than the intention behind it, and in that sense, all of us have the capacity to be philanthropists. She realized that giving starts with an impulse, and it’s wise to act quickly on that impulse. She became convinced that givers should trust the receivers to know best what to do with the gift. After giving, the givers should step aside, be all but invisible, while the receivers shine.

Her Princeton experience showed her one more thing: The returns on generosity are incalculable. Consider the Princeton roommate who spotted her $1,000. Could the roommate have known that the English major she helped stay in school would go on to become a novelist mentored by Toni Morrison — her thesis adviser — who would recommend her for the job where she would meet her future husband, whom she would help start an internet bookselling business that would revolutionize online retailing and make the couple one of the richest in history?

Jeannie Ringo Tarkenton ’92, that generous sophomore roommate, later founded a company, Funding U, which has provided $80 million in low-interest loans, without requiring co-signers, to about 8,000 students needing help to pay for college. Tarkenton demurs when asked about her impact on Scott’s trajectory. “I’ve always said she would have graduated without that grace, as would probably a lot of the thousands of kids I help because they are hardworking people who kind of try to figure it out,” Tarkenton says in an interview with PAW. “But small graces everywhere add up — or big graces, when it comes to MacKenzie’s” giving.

Scott, in her essay, portrays the roommates’ exchange and its aftermath as a parable of the kind of philanthropy she aspired to practice. Scott ended up loaning to Funding U a portion of the capital that Funding U has loaned to students, whose repayments are then loaned to more students.

“How quickly did I jump at the opportunity to support her dream of supporting students like she once supported me?” Scott wrote. “And to whom will each of the thousands of students thriving on those gratitude-powered student loans go on to give? None of us has any idea.

“Each unique expression of generosity will have value far beyond what we can imagine or live to see.”

Starting with a handful of donations in 2019, Scott, 55, has given $19.25 billion to more than 2,450 nonprofits, according to Yield Giving, her philanthropic organization. It’s a six-year tidal wave of funding possibly without precedent. She has donated more in that period than the lifetime giving of everyone on the Forbes 2025 list of the most generous American philanthropists except Warren Buffett, 95, (lifetime $62 billion); Bill and Melinda French Gates, 70 and 61, (lifetime $47.7 billion); George Soros, 95, (lifetime $23 billion); and Michael Bloomberg, 83, (lifetime $21.1 billion). Meanwhile, according to Forbes, Scott’s ex-husband Jeff Bezos ’86, 61, has given $4.1 billion.

Scott typically announces a large number of donations once or twice a year. In September, the Associated Press reported she had donated $70 million to UNCF, which plans to use the funds to bolster an endowment for scholarships at the nation’s 37 historically Black colleges and universities, and the Native Forward Scholars Fund announced it had received $50 million from Scott that will be used to support Native students pursuing higher education. Prior to those announcements, the most recent crop of gifts was unveiled in December — $2 billion to 199 groups, most of which “support the economic security and opportunity of people who are struggling,” she wrote.

Scott’s individual wealth comes from her 2019 divorce settlement with Bezos. She helped Bezos start Amazon in the couple’s garage in 1994 and was a back-office administrator in Amazon’s early days. In the divorce, she kept 25% of the couple’s Amazon stock — or about 4% of the company — while giving Bezos her interests in The Washington Post and Blue Origin, according to a tweet from Scott in April 2019. Her Amazon shares were valued at about $36 billion at the time; today her net worth is $34.8 billion, according to a recent estimate by Forbes. In 2011, the couple gave $15 million to Princeton to help build a center to develop neural imaging techniques, called the Bezos Center for Neural Circuit Dynamics.

Scott has remained largely silent about what motivates her philanthropy and how she chooses organizations to support. She has never granted an interview on the subject. She and her representatives did not respond to PAW’s repeated requests over five months for an interview. Liz London, senior director for global media at The Bridgespan Group, a leading philanthropy consulting firm that advises Scott and has served as a go-between with recipients of Scott’s gifts, declined to discuss Bridgespan’s work for Scott.

Public knowledge of what drives Scott’s approach to giving comes from the 11 essays she posted on Yield Giving’s website from 2019 to 2024. In several pieces she wrestles with the paradoxes of wealth and its just disposal. She implicitly accepts Andrew Carnegie’s 1889 dictum from The Gospel of Wealth — “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced” — but she also confronts how factors such as class, race, gender identity, and sheer luck influence the accumulation of riches. She insists that those forces be recognized in the endeavor to disperse the fortune.

“I have no doubt that tremendous value comes when people act quickly on the impulse to give,” she wrote in the first essay in May 2019. “We each come by the gifts we have to offer by an infinite series of influences and lucky breaks we can never fully understand … . I have a disproportionate amount of money to share. My approach to philanthropy will continue to be thoughtful. It will take time and effort and care. But I won’t wait. And I will keep at it until the safe is empty.”

A little more than a year later, in July 2020, as the nation reckoned with the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and the politicization of public health during the COVID pandemic, Scott wrote: “There’s no question in my mind that anyone’s personal wealth is the product of a collective effort, and of social structures which present opportunities to some people, and obstacles to countless others … . Opportunities that flowed from the mere chance of skin color, sexual orientation, gender, or ZIP code may have yielded resources that can be powerful levers for change.” Her own life, she continued, “had yielded two assets that could be of particular value to others: the money these systems helped deliver to me, and a conviction that people who have experience with inequities are the ones best equipped to design solutions.”

That month she announced $1.68 billion in grants to 116 organizations focused on what she called racial equity ($586.7 million), economic mobility ($399.5 million), gender equity ($133 million), global development ($130 million), public health ($128.3 million), climate change ($125 million), functional democracy ($72 million), empathy and bridging divides ($55 million), and LGBTQ+ equity ($46 million). Five months later, in December 2020, she gave another $4.2 billion to 384 groups. The issues she identified in 2020 have continued to attract the bulk of her giving, along with education.

Her essays hint that she avoids the spotlight in the hope of redirecting it to the communities and causes where local talent use her resources to create change. “Putting large donors at the center of stories on social progress is a distortion of their role,” she wrote in June of 2021. “We are attempting to give away a fortune that was enabled by systems in need of change. My team’s efforts are governed by a humbling belief that it would be better if disproportionate wealth were not concentrated in a small number of hands, and that the solutions are best designed and implemented by others.”

She sprinkles her essays with poetry, such as lines from the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi:

A candle as it diminishes explains,

Gathering more and more is not the way.

Burn, become light and heat and help. Melt.

The name of her organization itself is a clue to her approach and intentions. Yield Giving is a repurposing of a common term from finance and investing. At the top of her website, she defines “yield” by noting two of its meanings: “yield: (verb) 1. to increase. 2. to give up control.”

In a sense, Scott’s giving speaks for her. Experts in charitable donating say she has set a new model for the practice of philanthropy, not just in the scope and velocity of her giving, but also in the way she gives. Recipients can spend the money as they wish, or they can save it for long-term sustainability. There’s no deadline on putting the money to use, and there’s no requirement to report back to Scott. This unstinting faith in the judgment of the recipients about what their communities need — known as trust-based philanthropy — is a dramatic departure from so-called strategic philanthropy, a trendy approach favored by many tech billionaires in which donors tailor gifts to align with their own objectives and demand metrics to monitor their money’s impact.

“Part of what distinguishes her is the sheer scale and [short] amount of time that she’s done her giving in,” says Elisha Smith Arrillaga, vice president for research at the Center for Effective Philanthropy. “That is unprecedented.”

Arrillaga directed a three-year study of the effectiveness of Scott’s giving. The report, released in February, found that Scott’s gifts are strengthening nonprofits’ financial stability and enhancing their community impact. “It shows how transformational it is to give to organizations in this way,” Arrillaga says. Scott’s trust-based approach is also strategic, Arrillaga adds, because her team appears to deeply research the groups before granting funds.

According to leaders of organizations Scott supports, the flexibility of money from Scott is proving especially vital this year, as the administration of President Donald Trump curtails billions in federal grants and corporate underwriters shy away from causes disfavored by Trump, such as diversity, equity, LGBTQ+ support, and welcoming immigrants — areas where Scott has given heavily. Her most recent round of gifts — more than $2 billion to 199 organizations — was announced in December, more than a month after Trump’s election, though recipients started to be notified months earlier. Groups are using Scott’s money to plug holes where project-specific grants have been canceled, which would have been impossible if Scott had dictated how her money should be spent.

“It’s not just the federal funding freeze; we’ve also seen a lot of corporations and foundations start to pull back based on what’s happening politically,” says JB Stark, chief development officer of SAGE, which provides services and advocacy for LGBTQ+ elders and received $7 million from Scott in 2020. The group faces the loss of one-third of its budget in government grants. “Being able to rely on something like board-designated reserves that we have been able to build because of MacKenzie Scott is incredibly important.”

Scott is not the first philanthropist to give in this way, but she is a leading example, says Pamala Wiepking, associate professor at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. “What MacKenzie Scott is doing,” Wiepking says, “is helping [nonprofits] develop their capacities and work on those topics that they really think they should be working on, and not just what the wealthy philanthropists or leadership of large foundations think they should be working on.”

Still, the lack of clarity about Scott’s distribution of such vast sums troubles some scholars of charitable giving. Because she doesn’t donate through a tax-exempt foundation, she avoids legally required disclosures imposed on many large philanthropists. She reveals what she cares to on her website, which includes a searchable database of gifts she’s made. She lets nonprofits opt out of having the amount they receive publicized.

“Any rich person’s philanthropy constitutes an exercise of power insofar as they’re trying to direct their private assets to some public influence,” says Rob Reich, a professor at Stanford and author of Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better. “There’s a lack of transparency for her giving that you might think citizens in a democracy deserve more insight [into] if they wish to scrutinize her giving … . She’s so famously secretive that if you wanted to try to get her information, you’d have to have a whole bunch of insider knowledge about the intermediaries that actually run and host her philanthropic giving.”

Nevertheless, Scott’s giving patterns and the commentary in her essays have sparked conversations in philanthropic circles that perhaps here was a billionaire who wants to use her wealth to take on the inequities that help create billionaires in the first place while leaving others behind. “MacKenzie Scott is doing that which is antithetical to capitalism: redistributing wealth,” Edgar Villanueva, founder of the Decolonizing Wealth Project, wrote in The Washington Post in 2020. “Scott’s philanthropy is shattering archaic norms in the charitable sector by focusing on groups that have for too long been marginalized by philanthropy.”

Maybe that’s what irked fellow billionaire Elon Musk about Scott’s giving. In December, on his social media platform X, he posted a one-word reply to a critique of Scott’s support for “equity” and other causes: “Concerning.” He criticized Scott by name on X in 2022, and in March 2024 he posted and later deleted, “‘Super rich ex-wives who hate their former spouse’ should filed [sic] be listed among ‘Reasons that Western Civilization died.’” Scott and Bezos portrayed their split as amicable. Scott has never responded to Musk publicly, though two weeks after the March 2024 post, in what could be seen as a subtle rebuke, she announced another $640 million to 361 organizations with the same emphasis on equity and social mobility.

Scott “is among a small class of living individual donors who appear to have a deep commitment to these issues,” Megan Ming Francis *08, associate professor of political science at the University of Washington, who specializes in philanthropy’s relationship with social movements, tells PAW. “I don’t expect her to pivot, and I do not expect her not to give, or to freeze giving, as a number of funders have done since Trump has come into office.”

Mackenzie Scott Tuttle grew up in the San Francisco area wanting to become a writer for almost as long as she can remember. “I wrote my first book when I was 6 — 142 pages, but probably only 1,500 words or so, a chapter book about the adventures of a worm who loved to read,” she said in an interview published as an afterword to her first novel, The Testing of Luther Albright (2005), which won an American Book Award. “It took me almost a year of afternoons lying on our living room carpet with a stack of Oreos, a sheaf of kindergarten newsprint, and a fat pencil, and I distinctly remember the moment when it first occurred to me that I loved writing differently than I loved riding my bike or swimming.”

The family was well-off enough to send her to the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, but before she graduated, her parents and her father’s investment firm filed for bankruptcy protection. Her father was barred from serving as a financial adviser for violating records requirements of the Investment Advisers Act, according to a 1990 decision by an administrative law judge with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

At Princeton, she majored in English and entered the creative writing program, and also joined Cottage Club, according to the 1992 Nassau Herald and the 1992 Bric-A-Brac. “She was a very, very talented writer in college,” recalls classmate Doug Trevor ’92, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Michigan. “That was something that was known among those of us who were in the creative writing program … . If you had asked me what I would have expected from her, I would’ve expected her to go on and be a writer, not necessarily start Amazon.” Trevor also recalls her as “a completely charismatic, super smart person, but also very kind, very funny.”

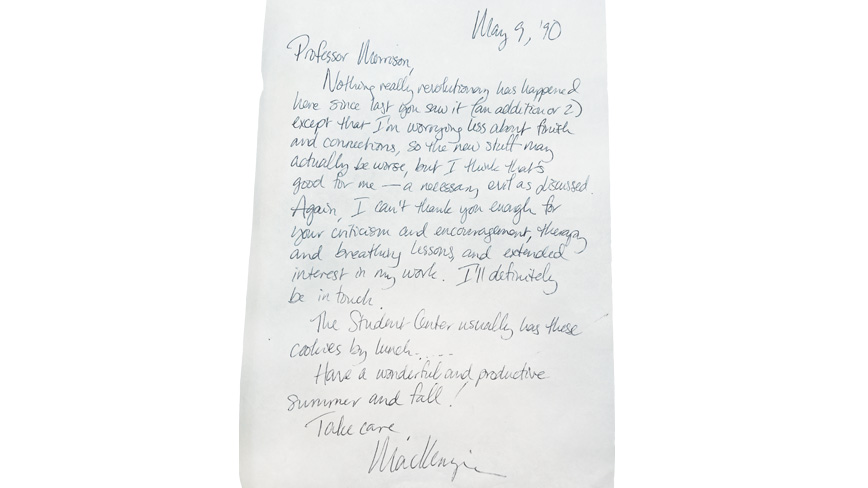

By the end of sophomore year, Scott was showing drafts of her writing to Morrison and embarking on a professional and personal friendship with the writer. Scott’s letters are preserved in the Toni Morrison Papers at Firestone Library.

“Professor Morrison,” Scott wrote in a handwritten note apparently attached to a draft in May 1990, “Nothing really revolutionary has happened here since last you saw it (an addition or 2) except that I’m worrying less about finish and corrections, so the new stuff may actually be worse, but I think that’s good for me — a necessary evil as discussed. Again, I can’t thank you enough for your criticism and encouragement, therapy and breathing lessons, and extended interest in my work.”

Her thesis was a 168-page novel called The Fathering Water, about an emotionally constrained engineer and his family leading a suburban life of quiet desperation. After graduating in June 1992, she taught writing for the summer at Hotchkiss. By September, living in New York City, she wrote to Morrison about her life as a restaurant server trying to become a writer. “My two weeks of waitressing in New York were not what I had remembered of my waitressing in Princeton. I found myself with unpredictable and small chunks of time during which I either collapsed from exhaustion and frustration or ruminated over the excruciating monotony of making and selling sandwiches and worried about how I might pay my rent with the nickels they gave me in exchange for my ennui.”

Her personal plot was about to take a Dickensian turn. In that same letter, she told Morrison that the week before, she had left waitressing for a job in recruiting at an investment bank. One of the executives who interviewed her was Bezos, who, Scott later told Morrison, hired her largely based on a transcript of the telephone recommendation that Morrison had given the firm on her behalf. Scott happened to be assigned an office next door to Bezos. Through the wall, she could hear Bezos’ distinctive guffaws. “That giant laugh, all day long,” Scott told Charlie Rose in a 2013 interview. “It was totally love at first listen.”

She invited Bezos to lunch. They were engaged within months and married a few months later, in 1993.

Scott — then known as MacKenzie Bezos — updated Morrison on her life in April 1995, still addressing her as “Professor Morrison.” “The new news is that last July, Jeff and I moved from New York to Seattle, where I’ve spent most of my time helping him start a business selling books over the Internet,” she wrote. “It’s an interesting business, and, on the whole, having a part-time job has been good for my writing … . I seem to be slowly producing a novel.”

It would be another 10 years before The Testing of Luther Albright was published, in 2005, followed eight years later by Traps, in 2013. Along the way, the Bezoses started a family, and MacKenzie Bezos became a Honda minivan-driving mother of four children. Every Thanksgiving, she sent cards to Morrison that included artwork by the children and photos of the family in sometimes silly poses.

Between birth notices of her children, the budding novelist also continued to send drafts of her writing to her Nobel Prize-winning former professor. Morrison received the first full draft of Luther just before the birth of the Bezoses’ first child in 2000. A draft or copy of Morrison’s response takes up two-and-a-half typed, single-spaced pages. It’s a detailed, nearly scene-by-scene, constructive critique of the manuscript’s structure and narrative voice. “Your hand is sure, your technical ability sophisticated,” Morrison wrote. She advised, “The rush toward the conclusion leads me to wonder if the ending is earned,” adding later, “Don’t worry about overdoing it at this point. I have as much disdain as you have for the heavy handed and the excessive. But it is so much easier to cut back or out than to write ‘up.’”

In 2014, near the end of the correspondence saved in the collection, the former student wrote to her mentor, “At every stage in my writing career, you have given me a kind of encouragement I particularly needed … . To me this seems like a stunning magic trick of empathy — perhaps ultimately unsurprising to anyone who has read your fiction, but it still brings tears to my eyes each time you do it.”

Scott joined Morrison on campus in 2017 for the dedication of Morrison Hall. Morrison recalled that in college her former student was already an “extraordinary writer, almost full-blown.” Scott lauded Morrison’s capacity to be simultaneously a great writer, teacher, and editor, saying, “She has given me a real example of a life of passionate devotion to more than one calling.”

Morrison died in 2019, the year of Scott’s divorce from Bezos. Scott has apparently published no more fiction since Traps, which is about four women caught in circumstances they are trying to work their way out of. Instead, her recent public writing amounts to her essays on philanthropy. The narratives she sets in motion these days are the storylines launched in thousands of communities where her money opens possibilities for countless striving characters.

To find out the difference Scott’s $19.25 billion might be making in people’s lives, PAW interviewed leaders of nearly two dozen nonprofits that received donations from 2020 to 2024. None will ever forget the unexpected phone call from a representative of a mysterious benefactor who turned out to be Scott.

“It maybe was a 10-minute call and I literally, as soon as I hung up, in the first few seconds, I just said to myself, ‘Did that really just happen?’” says Greg Maher, executive director of the Leviticus Fund, who got the call in the summer of 2024. Sure enough, $8 million was wired to the nonprofit community loan fund founded by nuns to create opportunities and healthier communities for low-income people in New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut.

Mike Curtin, CEO of D.C. Central Kitchen, was sitting in his office in southwest Washington in the spring of 2024, looking out at volunteers preparing thousands of meals. The person on the line got right to the point: $15 million was headed his way. “It was probably the best five-minute conversation I’ve ever had in my life,” he says. Using food to fight both hunger and generational poverty, the nonprofit provides culinary training and jobs. “What she’s saying is, I want to look at groups … that are making systemic change,” Curtin says.

Angie Gorn, CEO of the Norton Sound Health Corp. in Nome, Alaska, ignored the first email in 2023 from an unknown sender representing an organization she had never heard of, seeking to set up a phone call. “We all thought, that’s definitely spam, don’t respond,” Gorn recalls. A second email came two weeks later. Gorn figured she had nothing to lose. She took the call and gained $10 million for the health provider that serves members of 20 tribes living in tiny villages scattered across 23,000 square miles. “I don’t know how they heard about us or what it took to get on that list,” Gorn says.

The health-care nonprofit used most of Scott’s gift to build a clinic and residential triplex in Wales, a community without running water just across the Bering Strait from Russia. “We have a risk of polar bears coming into that community, so it’s important to have housing that’s really close, especially in snowy conditions,” Gorn says.

Gaby Pacheco, CEO of TheDream.US, happened to be in a musical instrument store in New York City in the fall of 2023. The call sounded to her like a choir of angels blessing her organization’s mission to provide college scholarships to thousands of immigrant students, including undocumented youths. TheDream is one of several groups that have received two grants from Scott, though Pacheco prefers not to disclose the dollar amount. “Her generosity is a beacon of hope for people,” Pacheco says. “She’s saying, here are the communities that are under attack. I’m going to stand up for them ... because I know how important and critical these communities are to the richness of our country.”

José Quiñonez *98, founder of the Mission Asset Fund based in San Francisco, listened to the caller in 2021 and “just started, frankly, just crying out of pure emotion,” he recalls. “The next morning I woke up thinking, did that just happen or did I dream it? Because there was no record, there was no email, there was nothing I could point to, except that I got a call from area code 206, which I think is the area code for Seattle,” where Scott is based. Quiñonez knew he wasn’t dreaming when $45 million arrived for his organization’s work to help people struggling economically, including immigrants, gain access to credit and financial stability.

The nonprofit leaders say Scott’s no-strings approach lets them apply the gifts to vital yet mundane-seeming general operations. Philanthropy experts say that’s traditionally the hardest purpose to fundraise for because many donors prefer to direct their money to attention-grabbing projects they can cut a ribbon on rather than, say, staff recruitment or internal capacity building. At the same time, Scott’s recipients also say they feel liberated to use the money on promising experiments. While some may fail, others may lead to breakthroughs in their fields.

Blue Star Families has directed much of the $10 million it received from Scott in 2022 toward new strategies to expand its nationwide mission to help military families connect deeply with their civilian communities. The strategies have included investing in staff talent as well as trying novel approaches to deliver programming, says CEO Kathy Roth-Douquet *91, who just completed a term as a Princeton trustee. (PAW’s random sample of Scott gift recipients included four nonprofits that happen to be run by Princeton alumni.) “It was a multiplicative effect beyond even what we had hoped,” Roth-Douquet says. “It did allow us the freedom, which I think is extraordinarily important, to experiment.”

“We are brazen, bold, stronger” because of “what MacKenzie Scott dollars have done,” says Allison Sesso, CEO of Undue Medical Debt, one of the rare nonprofits that has received three grants from Scott, totaling $130 million. Undue Medical Debt has canceled nearly $23 billion in patients’ medical bills after buying the debt from collectors. Rather than put all Scott’s money into buying debt, Sesso is using some of it to strengthen the organization’s capacity and operating systems, and also to invest in telling patients’ stories and crafting policy ideas. Scott’s gifts “have made me less concerned about, ‘Am I going to upset some funder if I say x, y, z thing,’ or ‘Where am I going to get the money to do that kind of work that will help move the conversation forward on medical debt and talk effectively about the policy solutions,’” Sesso says.

While Scott has extended her largesse to numerous familiar charities, such as Goodwill Industries, Habitat for Humanity, Boys & Girls Clubs, and Legal Aid chapters, she also bolsters sectors that have traditionally been underfunded, such as giving $560 million to historically Black colleges and universities. The gifts to 23 HBCUs in 2020 were among the largest grants ever to historically Black educational institutions. Scott also gave more than $100 million that year to colleges and universities serving Latino populations and tribal communities, as well as to other public institutions. Prairie View A&M University in Prairie View, Texas, put most of the $50 million it received from Scott into its endowment, to keep the university “stable and strong over time,” while using a portion for financial aid and to create the Toni Morrison Writing Program, Emma Joahanne Thomas-Smith, provost emerita and director of the writing program, tells PAW.

Scott often focuses her gifts on groups led by members of the communities they serve, frequently women, people of color, and those identifying as LGBTQ+.

“She’s been very intentional about the types of organizations” she supports, including “organizations that have a longstanding history of just not being in the right rooms, not necessarily having access to that type of investment,” says Kahina Haynes ’11, executive director of the Dance Institute of Washington.

Scott gave $2 million to the institute in 2024 for its work diversifying the next generation of professional dancers through a holistic instruction program that takes into account academics and life skills. Scott’s endorsement reassures other potential funders as they consider backing an organization led by a relatively young, Black, female artist, Haynes says. “For many of the folks that are kind of redacting their support” in the current political climate, she adds, “there are the MacKenzies who are like, ‘well, now we’re going to double down.’”

Scott’s giving addresses not only the marginalization of certain people but of entire regions, says Jacob Hannah, CEO of Coalfield Development in West Virginia. Hannah initially applied the $10 million Scott donated last year to leveraging hundreds of millions of dollars in federal grants to provide jobs, workforce development, and solar energy transition in Appalachia and other fossil fuel extraction communities across the country. But following recent federal cuts, “every single one of those grants are either paused federally or have been terminated,” he says.

Instead, as he hopes some grants will be restored, now Hannah is using a portion of Scott’s money as an emergency fund for dozens of rural community development nonprofits on the edge of bankruptcy because of the cutbacks and economic hard times.

“I hope one day this billionaire will be able to understand the impact they’ve had on Appalachian rural communities,” Hannah says. “No one [else] places trust in us to be able to manage funds ourselves or to allocate what we think is the best use of it … . This just unleashes us to do this work to the best of our ability. It’s truly transformative, and it’s not an exaggeration to say it’s a lifesaver.”

At the beginning of her philanthropic surge, Scott created a limited liability company called Lost Horse to help manage her giving. The name comes from an ancient Chinese parable that has fascinated Scott for years. She described it to Charlie Rose back in June 2013. “So there’s a farmer and he loses a horse,” she began.

The loss of the horse seems like a setback to the villagers, but the farmer says, “We’ll see.” The lost horse wanders back home with a companion horse, which seems like good luck to the villagers, but the farmer says, “We’ll see.” His son falls off the new horse and breaks his leg, which looks bad, but turns out to be lucky — and so on in an endless chain of misfortune masking opportunity, and opportunity concealing misfortune.

“The things that we worry over the most in life, the things that we feel trapped by, the mistakes we’ve made, the bad luck that we come across, the accidents that happen to us — the paradox is, in the end, oftentimes those things are the things we’ll look back and be the most grateful for,” Scott told Rose. “They take us where we need to go.”

At the time she chatted with Rose, just after the publication of Traps, Scott could look back and see the moral of the lost horse reflected in her own life. After graduation, she told Rose, if she’d had money and quickly banged out that first novel, she’d never have taken the job where she met Bezos. Later, by 2019, as she embarked on a post-Bezos chapter in life, Lost Horse was how she framed it in the name of her LLC.

“I went off to college knowing I was going to have to work a variety of jobs to put myself through school, maybe 30 hours a week on top of my course load,” she recalled to Rose. “And I got into Princeton, and I remember thinking, wow, this is a huge opportunity for me, Princeton. And worrying, because I was younger and didn’t have this kind of perspective yet, thinking, I hope that I can juggle these jobs and still get the most out of my education.

“And of course, what turned out to happen is that the jobs and the juggling were half of the education I got, right? So was it a setback? No, it was an opportunity.”

David Montgomery ’83 is a freelance journalist and former staff writer for The Washington Post Magazine.

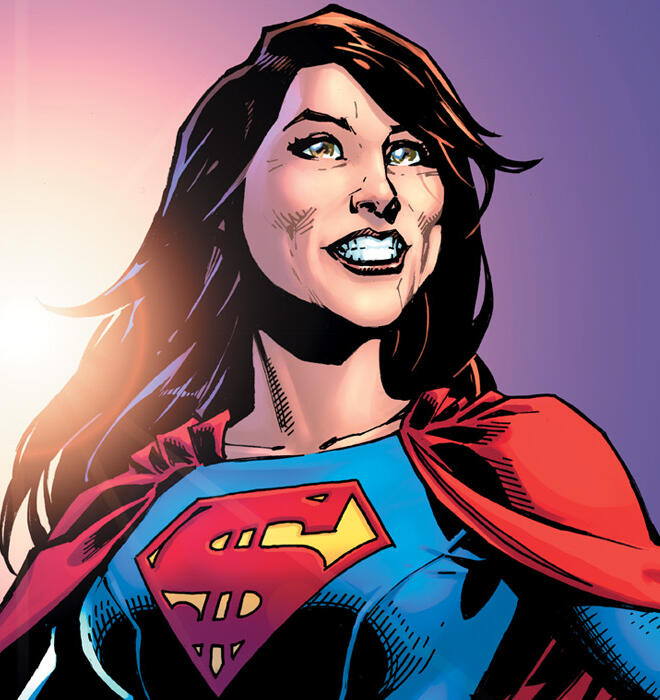

On the illustration: Jim Lee ’86, chief creative officer for DC Comics and a world-renowned artist, created the illustration of MacKenzie Scott ’92 that appears on PAW’s October 2025 issue cover. When PAW asked if he would take on the assignment, Lee quickly agreed. “Even though I’m not known for portraits or caricatures,” he said, “the power and impact of Scott’s philanthropic journey seemed to call for a superheroic take.”

12 Responses

Faith Yerkes-Short ’87

3 Months AgoA Portrait from Jim Lee ’86

Courtesy of Faith Yerkes-Short ’87

I loved seeing Jim Lee ’86’s portrait of MacKenzie Scott ’92 on the cover of the October issue.

It prompted me to rediscover my own, drawn in November 1983 and, since then, tucked in my Nassau Herald. Jim, a sophomore when I was a freshman in Wilson College, was a huge support during my — very wobbly — first year. He made me laugh and reminded me not to take things too seriously. I’m grateful for the memento and for the friendship.

Thanks, Jim!

Roland C. Warren ’83

4 Months AgoTrue Philanthropy Lifts the Vulnerable

While MacKenzie Scott ’92’s generosity is often celebrated, I must note a troubling place her wealth was given. She gave $275 million to Planned Parenthood, the nation’s leading abortion provider, which was the largest donation in that organization’s history. This donation aims to advance reproductive equity, primarily expanding abortion access in the Black community. Black women constitute just 7% of the U.S. population, yet represent 39% of abortions, highlighting stark racial disparities.

As a Black man, this deeply concerns me. Promoting abortion disproportionately in one community sends a harmful message that some lives are less valuable — the essence of racism.

This issue is personal. When I was a junior at Princeton, my girlfriend, a sophomore, became pregnant. The nurse who confirmed the pregnancy at McCosh immediately urged her to abort. She was told she would never graduate or achieve her dream of becoming a doctor if she kept the baby.

She didn’t listen. We chose life. We married, raised our child — who attended my graduation — and welcomed our second child shortly before her graduation. She went on to become a doctor, serving patients with compassion for over 30 years. The baby the nurse thought would “ruin” her life strengthened her resolve and purpose.

Now, I lead Care Net, a network of over 1,200 pregnancy centers offering life-affirming support to women facing unplanned pregnancies. True philanthropy uplifts vulnerable lives. Unfortunately, Scott’s gift funds death disguised as empowerment. What good is charity that excludes the most vulnerable — the unborn baby denied a chance to live?

Rocky Semmes ’79

2 Months AgoPlanned Parenthood Worthy of Scott’s Support

Roland C. Warren ’83, to his credit, leads Care Net, “a network of over 1,200 pregnancy centers offering life-affirming support to women facing unplanned pregnancies,” but he deceptively describes Planned Parenthood as an organization delivering “death disguised as empowerment” (Inbox, December issue). In a nutshell, Planned Parenthood would be needless and unnecessary in a world where all men were held equally accountable with women for pregnancies.

Globally, nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended (citing the United Nations Population Fund). Adequate contraception and timely pregnancy termination (yes, abortions) can go a long way to solving the problem of children brought into a world unprepared to receive them.

Mr. Warren pompously and piously calls Planned Parenthood a “troubling place,” and chides the philanthropy of MacKenzie Scott ’92 in its support. His Care Net pregnancy centers are to be applauded, but more (much more), needs to be done in a world where every other human being is unexpected. Until that solution is determined, Planned Parenthood serves a practical role, one worthy of purposeful philanthropic promotion.

Nathaniel Norman ’03

4 Months AgoPhilanthropy and Humanity

Good for MacKenzie Scott ’92 and her billions! Rather than add my voice to an unseemly chorus of sycophants falling over themselves to praise her largesse, I would like to offer an alternative view, expressed so elegantly and thoughtfully by Helen Keller more than 80 years ago. She wrote, “I regard philanthropy as a tragic apology for [the] wrong conditions under which human beings live.”

Rocky Semmes ’79

4 Months AgoOn the Gospel of Wealth

The phenomenally fabulous fortunes of MacKenzie Scott ’92 and Jeff Bezos ’86 rise from the same wellspring, a shared business venture in bookselling, but their respective biographies beyond that baseline speak volumes. Both being billionaires, there is a didactic distinction in the philanthropic divide between them. That divide is illuminating, eye-opening, and instructive in its illustration of character.

PAW writer David Montgomery '83 describes Ms. Scott’s philanthropy since 2019 as a “... six-year tidal wave of funding possibly without precedent.” According to Forbes, the total of her charitable giving stands at $19.25 billion, in stark contrast to the giving record of Mr. Bezos at $4.1 billion. Mr. Bezos’ generosity is indeed significant, but pales in comparison to the near five-fold comparative measure of Ms. Scott’s.

Where Ms. Scott is reported as “implicitly accepting Andrew Carnegie’s 1889 dictum from The Gospel of Wealth — ‘The man who dies rich thus dies disgraced,’” Mr. Bezos appears loath to part with his massively multiple billions of dollars, even though there is a line beyond which one’s comfort and ease is not increased by more money. One suspects the reluctance is fueled by ego, and in a comparative standing against others; a common male affliction.

Women more naturally exhibit empathy, seek and build community, and are prone to share. Men, in contrast are more predictably self-centered, thoughtless, and controlling. Cultural evidence is everywhere. Look around and consider what you see. The phenomenon to a degree might well inform the considerable donation divide of this former couple, and democracy being about how we forge a common life together, one questions why we elect men so often to its primary positions of power.

Geraldine Jackson

3 Months AgoGreat Article

Great article!

Dave Lewit ’47

4 Months AgoFunding Change with Charitable Support

Thank you PAW for your fascinating article on MacKenzie Scott! As a 99-year-old alumnus determined to donate almost all my assets to the cause of system change, Scott’s example confirms my relatively miniscule efforts. Though she gives her billions to established organizations, however small, I think she’d excuse me for negotiating a new research project jointly with two burgeoning low-budget organizations: the Albert Einstein Institution on nonviolent conflict, and Next System Studies at George Mason University.

I hope Princeton will excuse me for diverting this legacy to those small programs, which might otherwise have gone in part to our exceedingly better-funded university whose president, Christopher Eisgruber, leads academia against authoritarian bullying.

Tom Hirst ’64

4 Months AgoAn Inspiration to Do More

Just when the world has become so dark, mean, and nasty, here comes this astonishing, transformative lady philanthropist, Mackenzie Scott! She is such an inspiration! Thank you, PAW, for the wonderful article. Now I just have to figure out how to do more, better, to help mend the terrible tears in what used to be America’s social safety net.

Mitchell S. Muncy ’90

4 Months AgoDisappointed by PAW’s Coverage of Scott

The profile of Mackenzie Scott has to be one of the most embarrassing items to appear in the PAW since its May 1997 cover story on the actor David Duchovny. Like Duchovny, neither Scott nor anyone who works with her would even acknowledge PAW’s months of interview requests. As before, PAW responded to its target’s obvious indifference by doubling down with a jumble of previously published material, recollections of roommates, and third-hand tributes. At least Duchovny can be grateful that PAW recycled one of his publicity photos for the cover instead of commissioning a bizarre and tasteless caricature. Perhaps if Princeton didn’t have half its endowment locked up in private equity, venture capital, and real estate, it wouldn’t feel the need for this kind of creepy fundraising promposal.

Michael Goldstein ’78

1 Month AgoQuestioning Scott’s Giving

Well-said. It’s a celebration of Scott and her giving, particularly to Princeton, not an interview or profile. And perhaps because of her industrial-strength giving, lack of quality control, or her actual intentions, questions are being raised about some of the beneficiaries of her record-breaking largesse, which has surpassed George Soros.

As the Washington Free Beacon noted on Jan. 5, 2025, one of the recipients of Scott’s millions, Solidaire, “funneled millions of dollars to a left-wing nonprofit network that supports the nation's most virulent anti-Israel and anti-Semitic organizations, including some that are under congressional investigation for their ties to terrorist groups.”

Linda Jennings

4 Months AgoThree Cheers for Philanthropy

I’m thankful for all the efforts of philanthropists, in all of their charitable ways.

Mifflin Lowe ’70

4 Months AgoFrom a Fan and Author

Mackenzie Scott ’91 is my hero. I’d like to send her my recent, well reviewed and honored books that I think she will like. Forgotten Founders is about women and POC in the American Revolution. The DAR just selected it was the best book of the year on American history for young readers. The other book is The True West, about diversity in the American frontier. The publisher is Bushel & Peck, which gives away one book to underserved schools for each one it sells.