Martin Flaherty ’81 on the Supreme Court’s Power in Foreign Affairs

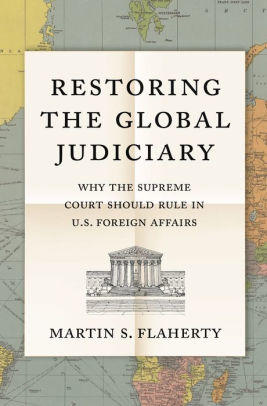

The book: The Supreme Court has been reticent to overturn controversial foreign-policy actions by President Trump, often under the justification that the president has significant leeway in handling foreign relations. In Restoring the Global Judiciary (Princeton University Press), Woodrow Wilson School professor Martin S. Flaherty ’81 argues that the Supreme Court has a historical and constitutional right to be a check on executive branch foreign-policy actions, and should exercise it for the good of the nation.

Flaherty argues that the judiciary was intended by the Founders to be a meaningful and independent branch of the government with respect to domestic and foreign matters. With that in mind, he analyzes how the Supreme Court has considered international cases throughout its history, and provides several examples of how the Court’s reluctance to consider foreign-policy actions has led to a less just democracy.

Opening lines: To appreciate the role of American courts in foreign affairs, it pays to go abroad. For me, the place to start was Beijing. Just before the turn of the millennium, I had the opportunity to spend a semester teaching law at China University of Political Science and Law, one of the country’s leading law schools. China then was sufficiently open to now-discouraged “foreign influence” that Fada, as it is known in Chinese, welcomed a course in English on U.S. constitutional law. For its part, the Chinese Constitution, or xianfa, could not be raised in court. Nor were courts independent, in any case. Undaunted, however, several brave reformers would soon try, with indirect success, to defend the rights of Chinese citizens by raising the xianfa before judges in specific cases. Fada, whose previous dean had defended student involvement in the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations, presumably knew just what it was doing by inviting an American to share a very different constitutional tradition, one that commanded respect around the world.

After some thought, I decided not to start with Marbury v. Madison, the great Supreme Court decision with which almost every American constitutional law course begins. Instead I selected Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, the “Steel Seizure case.” The controversy arose when President Truman, facing a national steelworkers strike during the Korean War, ordered an emergency federal takeover of steel mills to keep them running. The choice to lead off with Youngstown had in part to do with several iconic opinions. Justice Hugo Black wrote a majority opinion that is a model of what is sometimes known as “strict construction.” Justice Felix Frankfurters’ concurrence remains frequently cited for the idea that how the various parts of the federal government have operated over time serves as a “gloss” on the Constitution’s text. Most importantly of all, Justice Robert Jackson wrote a typically eloquent opinion that has ever since served as a classic framework for thinking about how the judiciary should resolve rival claims of authority between the president and Congress. But starting with Youngstown also had to do with the judgment itself. In essence, six unelected lawyers in black robes told a president of the United States that he was powerless to take an action he thought to be essential for conducting a war. What better case than Youngstown to show the awesome power of the American judiciary to maintain the rule of law, the Constitution, and, with them, basic rights?

Reviews: “In Restoring the Global Judiciary, Flaherty skillfully weaves together many strands of historical, legal, and empirical argument to demonstrate that judges must check and balance executive power just as much in foreign as in domestic affairs. The alternative is a global twilight zone in which individuals have no recourse against national governments. His proposals for the evolution of American law are bold and even shocking in the current environment, but deeply necessary.” – Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80, CEO of New America

No responses yet