Misrach Ewunetie ’24’s Death Ruled Suicide, Mercer County Prosecutor Announces

Princeton student found to have at least 59 pills in her system, according to autopsy report

Editor’s notes: If you or someone you know may have suicidal thoughts, you can call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat online at 988lifeline.org

This story has been updated.

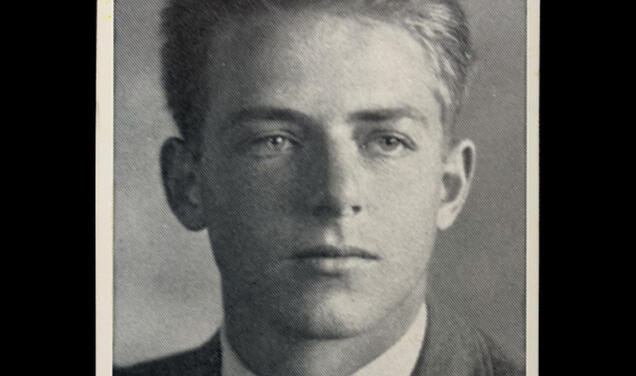

Misrach Ewunetie ’24, the Princeton student who was found dead on campus on Oct. 20 after a days-long search, died by suicide, the Mercer County Prosecutor’s Office announced on Wednesday.

A day later, the same office released autopsy and toxicology reports that detailed how the cause of death was determined. Among the findings were that at least 59 pills were in Ewunetie’s system and “journal entries describing past suicidal ideations with plan” were discovered in her dorm room.

The cause of death was declared to be toxicity of bupropion and escitalopram, which are commonly used to treat depression, and hydroxyzine, which can be used to address anxiety or provide relief for allergic conditions.

The autopsy was conducted by the Middlesex Regional Medical Examiner's Office according to a statement from the Mercer County Prosecutor's Office.

The Mercer County Prosecutor’s Office said Wednesday that it wouldn’t be providing additional information due to a request from Ewunetie’s family but released the autopsy and toxicology reports Thursday. Casey DeBlasio, public information officer for the Mercer County Prosecutor, did not immediately respond to request for comment on Thursday.

The autopsy report stated that Ewunetie had “multiple pills (at least 59) and pill-like fragments with granular consistency found” within her system and that empty pill bottles were found in her dorm room.

Ewunetie had been prescribed bupropion and escitalopram due to a clinical history of major depressive disorder and hydroxyzine for generalized anxiety disorder.

Her blood alcohol concentration was .084, just past the legal limit of impairment in New Jersey.

The autopsy report also noted that the investigation concluded with no evidence of foul play.

In an email to the campus community sent Wednesday afternoon, Rochelle Calhoun, vice president for campus life, wrote: “Our hearts go out [to] Misrach’s family and friends, and to the wider campus community that has been shaken by this tragedy. Losing a member of our community is always difficult.”

In an Oct. 20 press release, the Mercer County Prosecutor announced that Ewunetie, who had been a junior, was found dead behind the tennis courts and that “there were no obvious signs of injury, and her death does not appear suspicious or criminal in nature.” A spokesperson for the Mercer County Prosecutor’s Office previously confirmed the autopsy was conducted on Oct. 21.

According to a timeline of compiled by The Daily Princetonian, Ewunetie spent the night of Oct. 13 working at a Terrace Club party and was captured on footage leaving at 2:33 a.m. the following morning. At around 3 a.m., a suitemate saw her brushing her teeth in their dorm, but by around 4:30 a.m., she was gone.

“Terrace is focused on supporting our student members as they process this news, and will be planning a more permanent dedication to Misrach's memory in the near future,” Andrew Kinaci ’10, chair of Terrace Club's Graduate Board of Trustees, told PAW via email Thursday.

Though Princeton administrators assured the community that there was not an ongoing threat, security increased on campus in the wake of the tragedy.

A Nov. 1 email to the campus community announced new security measures, including restricting access to residential college dorms and locking common areas in residential colleges, as well as plans to enhance campus lighting and security cameras.

According to The Daily Princetonian, Assistant Vice President for Public Safety Kenneth Strother Jr. said in a Nov. 21 feedback session with students that cameras in most areas on campus are limited, and that while footage can be kept for up to six months, most footage is only kept for 30 days.

Ewunetie’s brother, Universe, told The U.S. Sun in October that his family felt the death was suspicious; he also insisted that his sister wouldn’t have taken her own life. A GoFundMe page raised $153,756 in donations for “assisting with the expenses associated with a funeral, an independent autopsy, and significant travel.”

Several vigils were held on campus for Ewunetie earlier this fall, with hundreds of mourners, including members of Ewunetie’s family, in attendance.

2 Responses

Martin Schell ’74

2 Years AgoUnfair Criticism

The PAW online letter from Yeates Conwell ’76 about reporting the suicide of Misrach Ewunetie ’24 strikes me as unjustified, from its appeal to a self-appointed authority (a website that proclaims it reviewed “over 100 peer-reviewed studies” without citing even one — a presentation of evidence that even Wikipedia would reject) to its peremptory use of “must” in the closing sentence.

I didn’t take any philosophy courses that specifically focused on epistemology, but it should be clear that PAW reported what was known when it was known. It is unfair to reprimand PAW for indicating “place” of death when that would be highly relevant if foul play had been involved. And posting a “photo” along with “details” (e.g., names of family members) is a standard procedure in the media for informing the community, who are expected to react with sympathy rather than a litany of rules about reporting.

Yeates Conwell ’76

2 Years AgoReporting the Tragedy of Suicide the Best We Can

PAW has reported the tragic death by suicide of a Princeton undergraduate. A major public health problem in the U.S., suicide is the 12th leading cause of death at all ages, and the second leading cause of death among the college-age population. Suicide is rare on university campuses but has pronounced adverse impacts not only for the person affected but for their family and friends and for the community as a whole. It is a newsworthy event.

Reporting of suicide, however, poses special challenges. Over 100 peer-reviewed studies published worldwide have shown that suicide can be “contagious,” increasing the risk of subsequent suicides among other vulnerable individuals. At the same time, responsible reporting may reduce that risk by changing perceptions, dispelling myths, and informing the public on the complexities of the issue and resources to address it.

Best practices and recommendations for reporting of suicides have been developed to guide the press in addressing this difficult topic most responsibly and effectively. (See, for example, www.ReportingonSuicide.org/Recommendations.) Among them are the need to avoid sensationalizing the event, describing the method and location of the death, including personal details or photographs of the person who died, or using terms that have may seem pejorative such a “commit suicide” with its connotation of a crime. More constructively, the report should keep details general, always include the best available data about suicide and its complex, multi-determined nature, and promote the message, with direction to mental health resources, that support and effective treatments are available for people who are having thoughts of suicide.

The PAW article succeeded in some ways in meeting these best practices, for example, by recommending that those experiencing suicidal thoughts call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chatline at www.988lineline.org. In other ways, however, it fell terribly short. Suicide prevention is everyone’s responsibility, and if tragically there is another instance in which responsible reporting of a suicide in the Princeton University community is needed, PAW must do better.