My sweet collapsing home

Katharine Greider ’88 chronicles the history and lives of those who dwelt in her town house

Katharine Greider ’88 cheerfully concedes that her former home at 239 East 7th Street in Manhattan is “unhistoric.” Nobody famous ever did anything significant there. Still, the place has intense meaning for her, considering what occurred in 2002, when Greider, her husband David Andrews ’89, their two children, and other co-owners hastily evacuated the three-and-a-half-story co-op after an architect discovered that its rotten foundation threatened to bring the 150-year-old town house crashing around them.

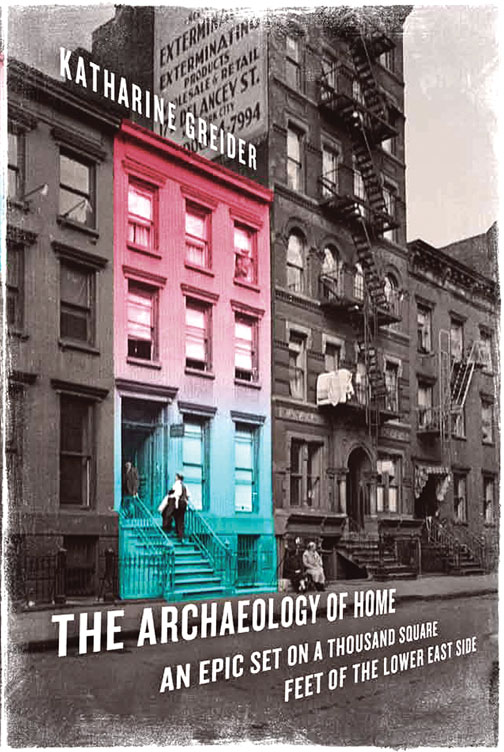

Greider starts her book The Archaeology of Home: An Epic Set on a Thousand Square Feet of the Lower East Side, published by PublicAffairs this month, with what happened after that warning sent them packing. She and her family moved across the street and spent 18 months in homeowner hell, struggling with two other owners of the town house, engineers, bureaucrats, bankers, and lawyers to resolve the structural and financial challenges.

From there, Greider expands her personal drama with ever-widening ripples of history about the development of the Lower East Side neighborhood, the Dutch and Colonial eras, and New York’s watery natural geography.

Ultimately, she muses about the very concept of “home” and the shock of displacement she felt away from her former house. She writes, “So home stores the most material of things — food, fire, water, babies, the bones of the dead — and highly abstract things — memory, expectation, rights, economic value.”

Beyond the physical structure of her home, she investigates its generations of inhabitants. Combing through census records, birth certificates, tax assessments, and wills, Greider re-creates the lives of families that preceded hers at the address. Greider wrote the book, she says, because “I was interested in how some spirit of the people endures and is incorporated in a place when you make a home there.”

The research created an emotional closeness between Greider and the ghosts of that house. Rachel Hart, for example, lived there for two decades starting in the late 1860s. Her husband died when she was 25, and her daughter Clara died of tuberculosis in the house when Clara was 28. Rachel spent the last 10 years of her life at the Manhattan State Hospital, an asylum on Ward’s Island.

“She drew a very short straw in life,” Greider reflects, but “her life had value, and I wanted to affirm that.”

The book keeps circling back to Greider’s efforts to return to and, finally, to extricate herself from the shaky pile she called home for five years. Freed at last from the house, which new owners gutted and rebuilt, her family bought another co-op nearby.

Van Wallach '80 is a frequent PAW contributor.

No responses yet