Neuroscience Researchers Study Trauma at the Border

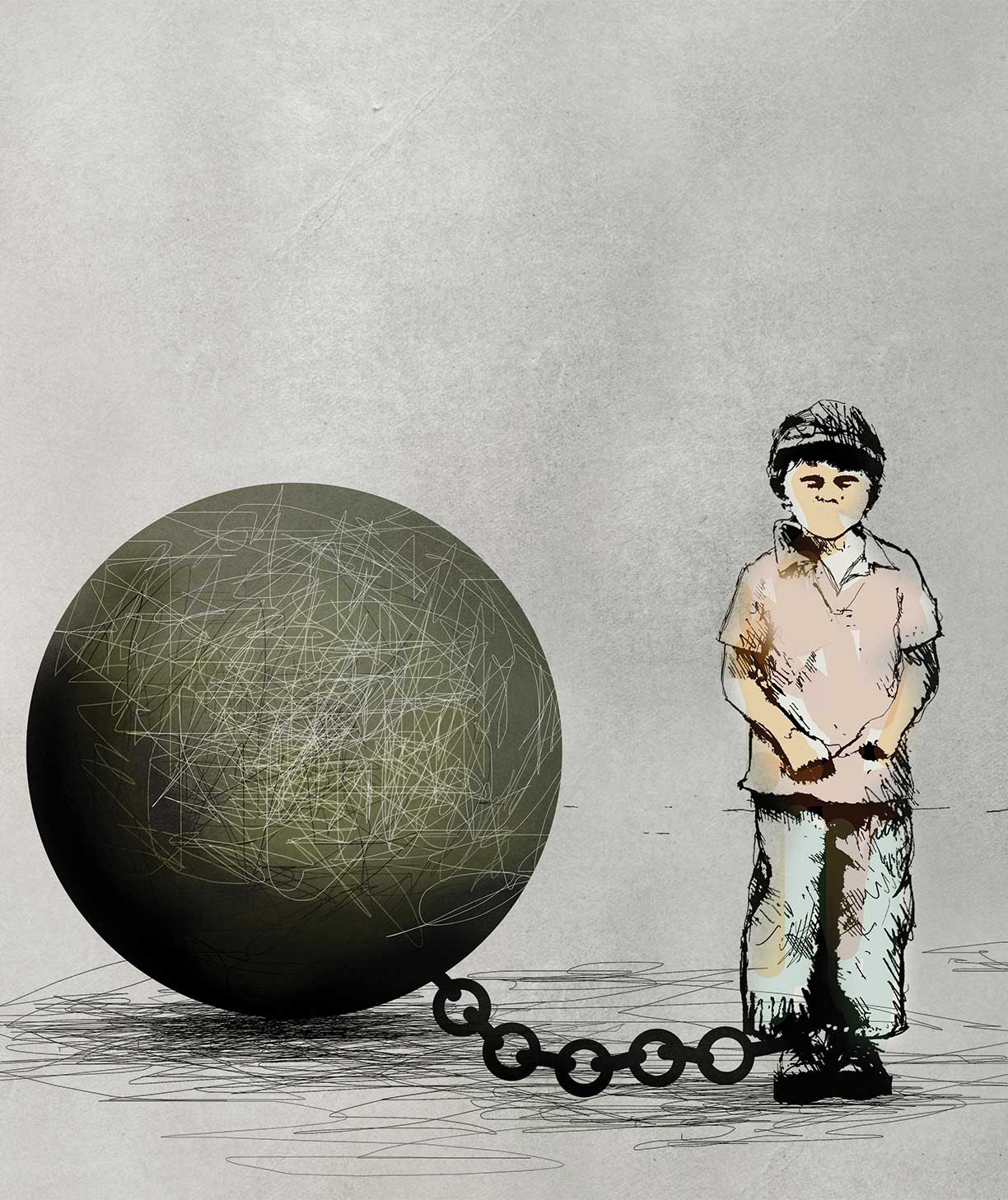

Professor and student study the mental-health effects of family separation

Around that time, Anne Elizabeth Sidamon-Eristoff ’20 joined assistant professor Catherine Jensen Peña’s lab at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute. The lab was studying the effects of early-life stress on mice, uncovering how this trauma primed the brain for mental-health issues such as anxiety and depression in adulthood. Sidamon-Eristoff, a Spanish major, asked Peña a simple question: How do you create that initial stress in a mouse pup?

“She said, ‘Maternal separation,’” Sidamon-Eristoff recalls. “I thought, ‘That’s weird, because that’s exactly what’s happening at the U.S.-Mexico border.’”

That lightbulb moment led Sidamon-Eristoff and Peña, along with two colleagues from the psychology department at Yale, to embark on a research study to determine whether family separation at the border increased the risk of post-traumatic stress disorders among the separated children. Over the course of that 2019 summer, they interviewed dozens of migrant parents and their children across six locations in Texas. They first determined whether the children had experienced any kind of pre-migration trauma such as violence, illness, kidnapping, or displacement; more than 97 percent of the children had. Next, the researchers assessed the children for signs and symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

The result? After the pre-migration trauma, family separation was the second-strongest predictor of PTSD symptom severity.

“It’s a particularly vulnerable population,” explains Sidamon-Eristoff, a clinical research assistant at Boston Children’s Hospital and incoming M.D.-Ph.D. student at Yale. “Detention and family separation just exacerbate the stress that they’ve already experienced.”

Their study joins a growing body of literature that suggests childhood trauma primes the brain for heightened responses to subsequent stresses, leading to greater risk of PTSD and its related problems — including depression, anxiety, and substance abuse — down the road. Peña points to research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Lancet Public Health that found children who have four or more traumatic early-life experiences are 30 times more likely to attempt suicide, three to four times likelier to experience depression or anxiety, and more than seven times likelier to become victims of violence, and are estimated to lose 20 years of life expectancy. The research also found that these children’s risk of cancer, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease was two to three times greater.

The good news, Peña says, is that early intervention can make a difference. So rather than separate families at the border, she suggests the government and nonprofit organizations actively try to mitigate the families’ stress responses to protect them and their communities.

“Normally what that would look like is just a warm, nurturing, stable environment, where you’re getting a lot of stimulation, reading, secure attachment with caregivers, communication, and community,” explains Peña, noting that even when immigrating families are ultimately granted residence, the government “sort of leaves them out to dry. We don’t give them the resources to create a stable home environment.” As a result, many of these children remain at risk.

This risk carries both social and economic implications, as those struggling with mental-health issues are more likely to end up in jail or drain health-care resources. Instead, keeping families together and providing them with resources to help mitigate the effects of pre-migration trauma, as well as offering them legal counsel during the asylum process to reduce uncertainty and stress, has “a mental-health benefit, an education benefit, and ultimately an economic benefit,” Peña says.

The researchers believe that their study helps drive smart immigration processes. “Our hope,” Peña says, “is that it can get to those who are making policy decisions, and influence public opinion enough, to tip the scales — to stop these policies that we know are detrimental to mental health.”

No responses yet