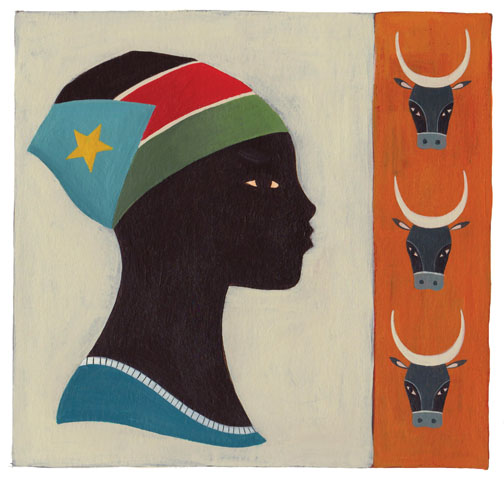

The new South Sudanese bride

The rains had stopped in October, opening up a view of volcanic mountains in the distance. Mounds of dust covered the dirt roads; an orange film stained dried-up plants bordering the only road for several counties. The onslaught of heat and the burning glow of the sun scorched the back of my neck. The land was lifeless and parched; there had not been a single drop of rain since the dry season began. Two months later, dust rose into my nostrils as we jolted back and forth on the road to the southern border of South Sudan.

Since I arrived in the capital city of Juba 10 months ago on a dirt tarmac, ready to embark on my one-year assignment at the U.S. embassy in South Sudan, my feelings of apprehension and anxiety had not fully dissipated. South Sudan celebrated independence on July 9, 2011, becoming the newest democracy in the world. Although free from the North, the fledgling country faces enormous challenges of deep ethnic tensions, conflict and violence due to the widespread availability of weapons after the war, and a citizenry with an illiteracy rate of more than 75 percent and little access to clean water, electricity, and educational opportunities.

Despite having an interim constitution and autonomous rule for more than six and a half years, South Sudan continues to grapple with advancing the rule of law and equality of men and women. It remains a strongly male-dominated society where traditional attitudes about gender persist. The founding father of South Sudan, John Garang, called women “the most marginalized of the marginalized,” and customary practices continue to discriminate against women and relegate them to objects of family wealth.

It has been months since I made that trip to the town of Morobo, in South Sudan near the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), yet I still think about it — particularly about a middle-aged South Sudanese woman, named Keji, whom I met there. I saw her pounding away at the earth with her shovel. I watched her closely as she readjusted the thinning strap of the sack carrying her 3-month-old daughter. When I asked about her daily routine, she replied, “I work and cook all day for my family.” But I saw more than that in the intensity of each throw of her shovel onto the soil.

Keji spends the first morning hours of each day digging into the earth in hope of a better harvest of cassava and groundnuts for her family of nine daughters. As the sun rises and the wind spreads the heat, drips of sweat trickle down her face and onto her oversized T-shirt — the last gift from a transient NGO worker who thought it might give the woman a bit of respite.

As midday approaches, she must trek five miles to the nearest borehole to fetch her daughters and idle husband two heavy pails of water for the evening meal. She warms the blackened clay pot over burning coals on the side of the family’s rounded tukul, or small hut. While she grinds the grainy, white sorghum into a powder on a wooden palette, her older daughters wash the pots and dutifully mind their two baby sisters, unaware of the future that awaits many young women — a future limited by early marriage and pregnancy, cutting education short.

Fifteen years ago, Keji was forced to marry at a young age to improve her family’s financial status; in return for a wife, her new husband’s family paid a “bride price,” in cattle. The status of a woman in society depends on the wealth — valued in terms of the number of cattle — that she is able to provide for her family. Like her own daughters, Keji lived a life where her father did not work, where the parents did not have enough cows to feed their family of six, and where her family members were outcasts in the bordering region of the DRC as the civil war continued endlessly. At the time of her marriage, she was still an adolescent, her chest as flat as an ironing board.

She says her life could have ended on the day her eldest daughter, Mundara, was born: The birth caused excessive bleeding, and the baby came six weeks early and weighed a mere four pounds. Keji says she and her baby survived only because a khawaja, a foreigner, who worked with an NGO drove her to the nearest clinic with a midwife, 15 miles away.

Today, the women of South Sudan are mired between tradition and 21st-century modernity. Their fathers, brothers, and husbands fought vigorously for freedom, democracy, and human rights, yet the women are unable to see these newfound ideals develop into gender equality. They have constitutional rights and serve as members of Parliament, giving the illusion of power. Unless the young nation addresses traditional, discriminatory practices and educates women about exercising their rights, women will continue to be marginalized and prevented from achieving full equality in South Sudan — leaving them little opportunity to experience the freedom and the founding principles on which their country was built.

Weeks after I meet Keji and her daughters, I find some solace in better understanding the lives of women from a different culture, facing challenges different from my own with strength and hope.

And so the image of Keji’s daughters sticks with me. I see them preparing the evening tea; Mundara, now 13, finishes heating the water over the coals. She is tall and slender — a mark of her Dinka heritage. Soon her father will consider her for a bride price. Her physique should bring a high price in a bidding war this year. The man with the most cows will become her husband.

Sandya Das *08 is a Foreign Service officer living in South Sudan. She previously served in Mumbai, India, and earned an M.P.A. degree at the Woodrow Wilson School.

No responses yet