Newsmakers Q&A: Elizabeth Winkler ’11 Dissects the Furor Over Shakespeare’s ID

Winkler asks: Why does a question about the authorship of 400-year-old plays get people so riled up?

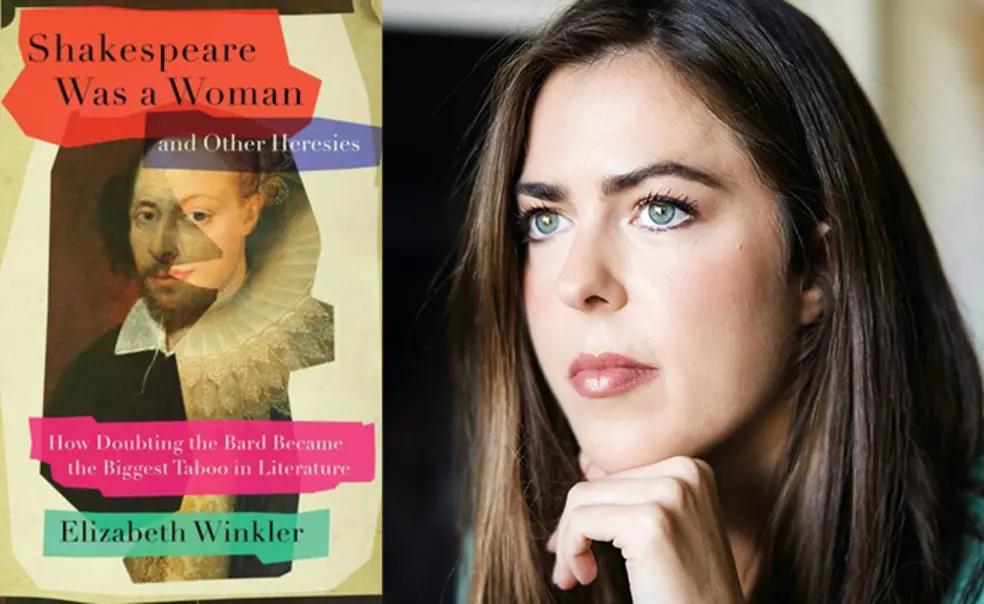

After Elizabeth Winkler ’11 graduated from Princeton, she went on to graduate school at Stanford before turning to journalism. She is currently a critic and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her articles and reviews have appeared in TheWall Street Journal, The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Economist, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Atlantic. Winkler’s first book, Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies, was published in May 2023. The book is being taught in a Harvard history course this semester on historical controversies.

Tell us about your recent book and writing experience.

It’s about the strange, centuries-long feud over who wrote the works of Shakespeare. Many writers and thinkers over the years have suspected [Shakespeare] was a pseudonym for a concealed writer. Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Henry James, Sigmund Freud, Hemingway, Nabokov, multiple Supreme Court justices, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Roger Penrose, Shakespearean actors like Mark Rylance and Derek Jacobi. The list is extraordinary. It includes academics, too — professors of theater, philosophy, history, psychology.

But within English literature departments, there is a kind of taboo around the topic. Shakespeare scholars admit that the bard’s biography is a “black hole,” but you don’t question the authorship. If you do, you tend to provoke emotional and sometimes furious responses. That’s what I wanted to investigate. The subtitle of the book is How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature. Why does a question about the authorship of 400-year-old plays get people so riled up?

The book is part literary history, part investigative journalism, examining how Shakespeare came to be regarded not just as Britain’s greatest writer but as a god, a figure beyond questioning. It’s about belief and doubt, nationalism and empire, religion and myth-making. Along the way, I interview leading Shakespeare scholars as well as skeptics. I spoke with Stanley Wells in Stratford-upon-Avon, Michael Witmore at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Stephen Greenblatt and Marjorie Garber at Harvard. I also went to the Folger to read correspondence between Professor James Shapiro and the late Justice John Paul Stevens — a fascinating exchange between the two. The skeptics I interviewed include Mark Rylance, Alexander Waugh (grandson of the novelist Evelyn Waugh), and various scholars.

I’ve come to see the authorship question as a kind of metaphor for the problem of history, of how we know what we think we know about the past. It’s also a metaphor for the problem of authority: Who has the authority to determine the truth about the past? In the book, I don’t argue for any particular candidate. I explore the different theories (or heresies): Was it the Earl of Oxford? Christopher Marlowe? A group of writers? Was a woman possibly involved in the creation of these remarkably feminist dramas? It’s a portrait of a muddled, fractious controversy by a journalist surveying the history of the debate. I wanted to let readers struggle with the gaps, problems, and inconsistencies without telling them what to think. Ultimately, it’s really a detective story, a whodunit. It’s the biggest mystery in literature and an awful lot of fun.

Do you have any new projects in the works?

I’m doing lots of talks and events about the book. I’m also focusing on other journalism — book reviews, essays, cultural reportage. I want to write another book — probably something that will evolve out of an article, combining interviews and criticism again. I loved the experience of building and structuring a complex, compelling, book-length narrative that keeps the reader engaged. It was hard at times, but now that I’ve done it once, I think I’m hooked.

—Interview conducted by Sophie Steidle ’25

3 Responses

Brent Evans

2 Years AgoWho Decides What Is True?

Elizabeth Winkler’s book is a reasoned and reasonable inquiry into orthodoxy and how it is established — and how entrenched a notion can become. There have always existed questions regarding how the greatest literature in the English language came to be. Which is more likely, that Shakespeare was a pseudonym for someone who was highly educated, multilingual, and well-traveled, or the name of someone with no verifiable education and no evidence of even owning a book? Orthodox English literature scholars refuse to examine the mountain of historical evidence or even acknowledge there is an authorship problem. Ms. Winkler’s book examines why the issue is so radioactive among traditional academics and how difficult it is for this or any orthodoxy to be overturned.

Elisabeth Pearson Waugaman *70

2 Years AgoParadigm Shifts Are Slow and Difficult

Elizabeth Winkler dares to addresses the Shakespeare authorship question; and thus finds herself facing severe blowback for challenging a paradigm. I discovered this problem when I stumbled upon spectacular studies by French scholars, Abel Lefranc, member of the Académie française, “Sous le masque de William Shakespeare” (“Beneath the Mask of William Shakespeare,” 1918-1919) and Georges Lambin, “Voyages de Shakespeare en France et en Italie” (1962), which English-speaking scholars simply refuse to acknowledge. These French studies reveal Shakespeare’s surprising knowledge of French, of secret French political intrigues (not put into print until after his death), as well as shockingly accurate descriptions of major and minor French historical figures, and detailed knowledge of Italy and France, which reveal it is English scholars, not Shakespeare, who don’t know Renaissance geography. Based on an untranslated French story, Hamlet was performed in 1593; but Shaksper only began to, possibly, learn French when he boarded with a French Huguenot family in 1602. All of this is buried in complete silence.

Paradigm shifts are very difficult and take time. Hopefully, Winkler’s book will finally open doors slammed shut for far too long. Once they open, it’s “a brave new world,” and we discover Shakespeare is even more amazing than we were allowed to know.

Richard M. Waugaman ’70

2 Years AgoAn Alum Princeton Can Be Proud Of

Thank you for Sophie Steidle ’25’s interview with Elizabeth Winkler ’11 (Newsmakers Q&A, published online Feb. 13). Her book on Shakespeare is the most important recent book on Shakespeare by a Princeton alum or faculty member.

Elizabeth courageously takes on a taboo topic. Having read dozens of reviews of her book by the general public, it’s clear to me that many educated people are shocked by the vitriol that has been hurled at Elizabeth for her exceptionally professional treatment of this topic. She is a top-notch investigative reporter who has exposed the false claim that we are 100% certain that Shakspere of Stratford wrote Shakespeare. Harvard’s eminent Shakespeare scholar Marjorie Garber told Elizabeth it doesn’t matter to her who the author was.

Elizabeth’s Princeton education has taught her the importance of critical thinking, especially about assumptions that are not to be questioned because of the powerful unconscious effects of groupthink.

I hope all Princeton students, faculty, and alums will read her entertainingly informative book.