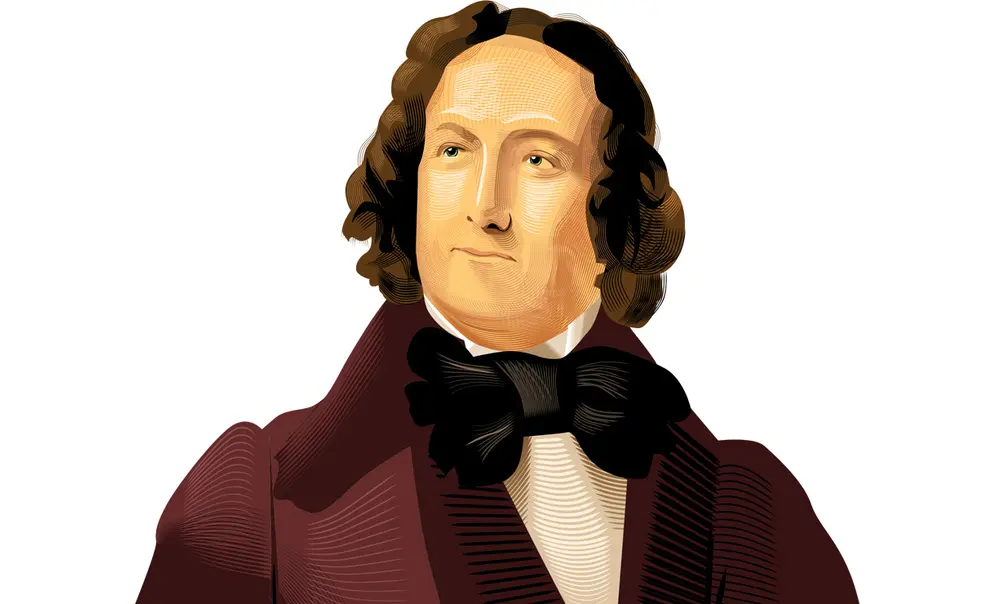

Nicholas Biddle 1801 Opposed Abolition and Facilitated the Slave Trade

Nicholas Biddle 1801 (1786-1844)

In May 1806, a 20-year-old American military officer stepped onto the shore of Greece, then a part of the Ottoman Empire. The man’s name was Capt. Nicholas Biddle 1801, and he was only the second American citizen to visit the Hellenic homeland. As a Turkish customs official greeted him with a lamb dinner, Biddle was stunned to find the modern Greek landscape so different from the ancient Greece he had read about during his studies at Princeton, writing, “I was alone in a foreign country distant from all that was dear to me, surrounded by barbarians who yet occupied a soil interesting from its former virtues and its present ruin.”

Biddle was 13 when he entered the College of New Jersey, as Princeton was then known. A prodigy from a wealthy Philadelphia family, he graduated as valedictorian in 1801, destined for a prominent place in the leadership of the young republic. But Biddle had a dark side, and his rise to power helped perpetuate the suffering of millions of slaves.

As Joseph Yannielli of the Princeton & Slavery Project uncovered, at Princeton Biddle wrote an essay against the abolition of slavery, arguing that if slaves were freed, they would suffer without the “support” of plantation owners, “as no nation is more lenient towards its slaves than America.” Biddle also worried that freed slaves would rise up and form a “much more formidable enemy even than the Indians,” threatening the violent overthrow of white society.

Biddle took those views with him as he ascended through the hierarchy of the new American aristocracy. Through a family connection to Vice President Aaron Burr Jr. 1772, after graduation Biddle took a job as an assistant to the ambassador to France. But Biddle didn’t remain in the job for long, and instead decided to pursue a tour of the places he had studied at Princeton, including Italy and Greece.

On his way back to America, he made a stop in Cambridge, England, where his knowledge of the Greek situation impressed the U.S. ambassador, James Monroe. In 1819, two years after Monroe became president, he appointed Biddle to a position within the Second National Bank, and in 1823, Biddle became the bank’s president, an office he occupied for 13 years. A forerunner of the modern Federal Reserve, the Second National Bank managed the national debt, issued currency, and lent to state banks.

Recent research by historian Stephen W. Campbell has revealed that Biddle’s management of the Second National Bank was instrumental in facilitating the cotton trade and the institution of slavery. By enabling transactions between plantation owners and cotton merchants, the Second National Bank supported the slave trade and made plantations more profitable. And as the U.S. expanded, Biddle also helped increase the spread of slavery, signing off on a loan to the new Republic of Texas, which had declared independence from Mexico, to continue its plantation-based economy.

Meanwhile, Biddle saw himself as the inheritor of the classical world. He determined that Girard College, a prep school for orphans in Philadelphia, would be designed with neoclassical architecture; he also remodeled his Philadelphia mansion “Andalusia” on the Temple of Hephaestus he had visited in Athens.

But such heights were not to last. In 1832, Biddle’s bank drew the ire of President Andrew Jackson, who distrusted all banks and refused to renew the bank’s charter. During the ensuing “Bank War,” Biddle engineered a financial crisis to prove the value of his institution, an effort that backfired and turned public opinion against him. In turn, Jackson’s successful dissolution of the bank’s federal charter in 1836 incited a recession.

Biddle’s career ended in scandal, as a grand jury indicted him for illicitly borrowing bank funds. Though the charges were dropped, Biddle lost all his money when the bank, rechartered as a Pennsylvania institution, failed in 1841. In 1842, Charles Dickens, upon visiting the shuttered bank, described the building as “the Tomb of many fortunes; the Great Catacomb of investment; the memorable United States Bank.” At present, Girard College, the institution Biddle supported in its mission to educate orphaned boys, continues to provide education and scholarships as a coeducational boarding school for underserved students. Today, 93% of those students are Black.

No responses yet