In 1831 a pair of French 20-somethings set off on a road trip through the young United States. Alexis de Tocqueville was the sensitive, introspective, and brilliant son of an aristocratic family that could trace its heritage back to the time of William the Conqueror. Gustave de Beaumont was his ebullient and charming friend. Commissioned by the French government to study American penitentiaries, the pair was after much more.

Over the course of nine months Tocqueville, 25, and Beaumont, 29, traversed 17 of the 24 states and three regions, traveling by steamboat, stagecoach, horseback, and canoe. They proved tireless investigators, engaging Boston elites and Ohio cabin-dwellers in endless conversations about American society, which they dutifully wrote up at night. Afterward, Tocqueville produced his hallmark of American political theory, Democracy in America, arguing that what made American democratic institutions work was the collective investment of the whole population.

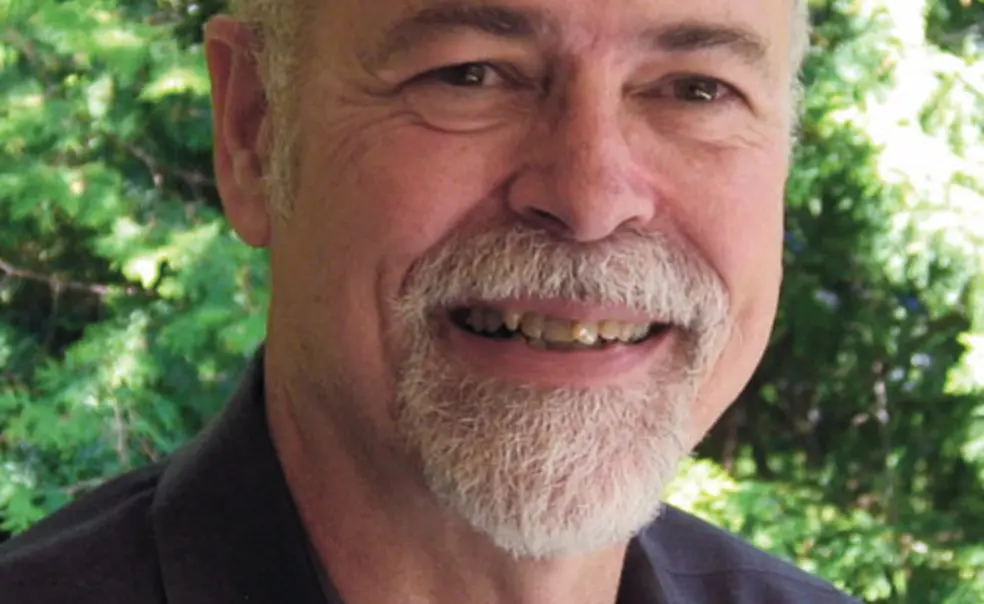

“I hadn’t realized how much of Democracy in America was practical and how much was based not on Tocqueville’s independent theorizing, but really from thinking through and deepening what he knew about America,” said Leo Damrosch *68, whose book Tocqueville’s Discovery of America, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux this month, tells the story of Tocqueville and Beaumont’s friendship and their transformative journey through the United States.

A literature professor at Harvard, Damrosch combed through Tocqueville’s letters and notebooks. Many of the most telling details of Tocqueville’s journey, he says, never had been translated into English. Tocqueville’s Discovery of America is jam-packed with just such nuggets.

Tocqueville wrote a detailed account of reading Shakespeare’s Henry V while recovering from a dangerous fever, snowbound in a log cabin in Tennessee. The world of rural America disappeared and he imagined “high turrets and a thousand banners floating in the air.” He expressed pain and grief at seeing a band of Choctaw Indians marching westward as part of the forced relocation of Native Americans called the Trail of Tears — a spectacle, he said, “that felt like a final farewell with no returning.” Tocqueville and Beaumont bumped into Texas governor Sam Houston aboard a steamboat on the Mississippi and found him a ready conversationalist. They went searching for a little island on New York’s Oneida Lake that was the setting for a favorite French children’s story. They marveled at Americans’ disregard for traveling long distances, were aghast at their table manners, and found that the chastity of American women forced them to practice a “most austere virtue.”

Writing for a popular audience, Damrosch said he hoped to make Tocqueville come to life, as his previous book Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius, a National Book Award finalist, did for the 18th-century philosopher and writer.

Democracy in AmericaAnne Ruderman ’01 is a graduate student at Yale University.

No responses yet