Ornithologist John Fitzpatrick *78 Fosters Deep Connection to Birds

‘Early on, I said birds supply so many different powerful opportunities,’ Fitzpatrick says

“An ornithological giant” is how Judith Scarl, executive director of the American Ornithological Society, describes Fitzpatrick. “He’s one of the best respected and most well-known ornithologists of our time. His leadership helped foster deep connections to birds and birdwatching throughout the U.S. and beyond,” she says.

“Early on, I said birds supply so many different powerful opportunities. We can be a bouquet of different projects that fit together. Our K-12 program is very different from the Bird Academy, our educational platform for lifelong learners, and from our conservation bioacoustics program.”

Elected in 2020 as a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Fitzpatrick oversaw the creation of eBird, a global bird-observation website. The world’s biggest citizen science project and biodiversity database, the 20-year-old project has recorded more than a billion observations of different species of birds.

“The consequences are just enormous,” says Fitzpatrick. “We can now look at bird populations, movements, and population trends across continents. Because birds are so informative about ecological systems, by proxy eBird gives us a reading on how things are going in all the world’s ecosystems.”Prior to Cornell, the St. Paul, Minnesota, native chaired the zoology department at the Field Museum in Chicago and was director of the Archbold Biological Station, a Florida environmental research center in a scrub ecosystem near Ft. Myers.

The Endangered Species Act had made it illegal to clear land with active Florida scrub-jays, and when Fitzpatrick learned a bulldozer had been sent to clear the land so orange trees could be planted, he didn’t hesitate.

“I went out with my movie camera, stood there, and the bulldozer came down towards me. The guy in the tractor looked at me, turned around, went up to the top of the hill, turned the motor off, and drove away, and that place is now a state wildlife refuge,” he says.

The moral of the story? “Get out there and stand for something,” says Fitzpatrick.

He had planned to do his graduate work at Berkeley after graduating from Harvard, but then he had a chance meeting with Princeton ecology and tropical biology professor John Terborgh, who was about to leave on a summer expedition to Peru. Terborgh, he recalls, said: “For God’s sake, come with me.”

“He taught me a huge amount about thinking, designing, and carrying out ambitious expeditions in remote areas of Peru, which I then did for the next 15 years,” Fitzpatrick says.

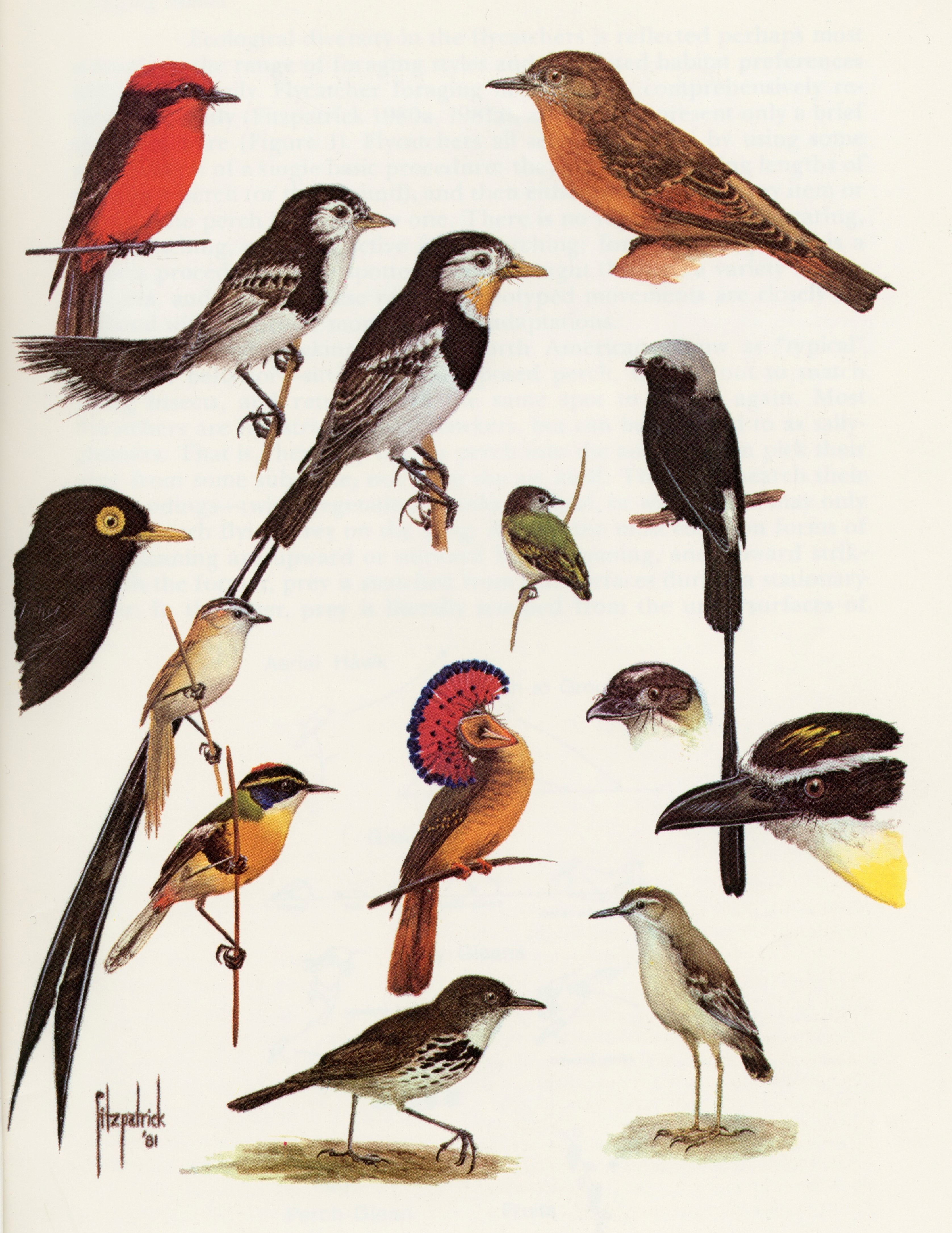

While doing his doctoral research, Fitzpatrick documented seven new bird species in Peru’s Cordillera del Cóndor mountain range and Manú National Park. “Six of them are formally called species. The seventh I described as a subspecies, but I should have called it a species at the time, so I like to say seven,” he says.His lifelong love affair with all things avian, including painting watercolors of birds, began one spring morning when he was a kindergartener. While sick at home, he saw what he thought was an oriole outside his living room window. He flipped through his parents’ copy of the Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America and discovered that the stunning black and bright orange warbler was a male American redstart.

“God, look at all those birds,” he remembers thinking as he looked through the book.

Today Fitzpatrick has a different favorite — the red-breasted nuthatch.

“I’ve been in love with this little pumpkin-seed-sized bird all my life. Anytime you see the red-breasted nuthatch, you’re in a cool place,” he says. “It’s just a cute little thing.”

No responses yet