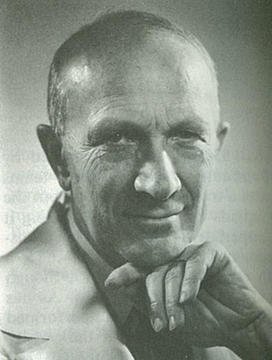

Wilder Penfield 1913 — Victorian Gentleman, Renaissance Man

From the PAW Archives: July 1976

The Google doodle for Jan. 26 featured the late neurosurgeon Wilder G. Penfield, Princeton Class of 1913, in honor of his 127th birthday. The following remembrance, from PAW’s July 4, 1976, issue, highlights Penfield’s remarkable achievements in medicine, his later work as a novelist and biographer, and his brief tenure as Princeton’s head football coach.

Best known for his pioneering achievements as a neurosurgeon and brain researcher, Wilder G. Penfield ’13, who died of cancer last April 5 in Montreal at the age of 85, was truly a Renaissance man. An outstanding athlete and president of his class as an undergraduate, he stayed on a year to serve as Princeton’s head football coach. A Rhodes Scholar at Oxford during World War I, he spent his vacation breaks in France as a dresser at a military hospital; and when World War II arrived, he became a colonel in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. After retiring as founder and director of a major research institute, he continued his role as an educator, lecturing widely, and began a second career as a novelist and biographer. In fact, he became a leading advocate of second careers for retired people, and devoted his last years to defending the value of the nuclear family in child development. Countless awards and honors were bestowed on him by professional societies and governments.

A decade ago, in introducing him at an international conference, Donald W. Griffin ’23 noted the Penfield “grew up in the twilight years of the Victorian era. All his life he has carried himself with the grace and gallantry of that world long since gone. … Scholar, athlete, surgeon, discoverer, administrator, teacher, author, and soldier, but first and always a man — a true gentleman cast in the heroic mold which his modesty disguises.”

Although his father, who died when Penfield was a boy, had been a physician, Penfield did not plan on a medical career until he became fascinated with the biology lectures of Professor Edward Grant Conklin at Princeton. But it was the influence of Sir Charles Sherrington at Oxford that led Penfield to specialize in neurology. After receiving his M.D. from Johns Hopkins University in 1918, he spent the next decade at a number of hospitals and medical schools in the U.S. and abroad, developing advanced neurosurgical techniques.

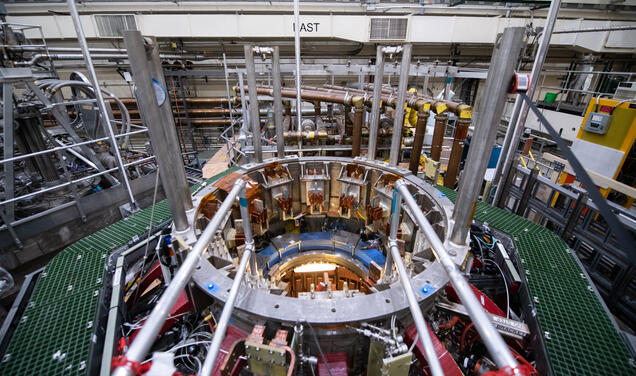

In 1928, Penfield moved to Montreal, where he perfected the surgical operation for severe epilepsy which first brought him fame. The method involves exploring the regions of the brain with an electrode while the patient, under a local anesthetic, remains conscious so he can help the physician locate the damaged section, which is then removed by surgery. A complete cure is effected in about half of the cases, and in another 25 percent a significant improvement in the condition results.

Using similar techniques, Penfield began mapping the various areas of the brain where different mental activities — sight, hearing, speech, etc. — take place. He also discovered, quite by accident, that touching certain parts of the temporal lobes with an electrode can trigger detailed memories of the distant past, almost like turning on a tape recording of the patient's consciousness at the time.

With a $1.2-million grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Penfield founded the Montreal Neurological Institute in 1934, which soon became one of the world’s most famous centers for brain surgery and research. During World War II, he directed a number of military-medical projects, including investigations of motion sickness, decompression sickness, and air-ambulance transport of persons with head injuries. Following the war, he undertook a study of epilepsy caused penetrating wounds of the brain and worked on the removal of brain scars resulting from birth injuries.

After retiring as director of the institute in 1960, he wrote The Torch, a biographical novel about Hippocrates, “the father of medicine,” and a biography of his late friend Alan Gregg, the foundation executive who approved Penfield’s Rockefeller, The Difficult Art of Giving. He also became president of the Vanier Institute of the Family, believing that “the problem of lack of discipline in society, juvenile delinquency and crime, can best be faced at the level of the family.” He completed his own autobiography, entitled No Man Alone, just a few weeks before his death.

No responses yet