Perspective: My American Dream

Why this Princetonian takes immigration reform personally (from the PAW archives)

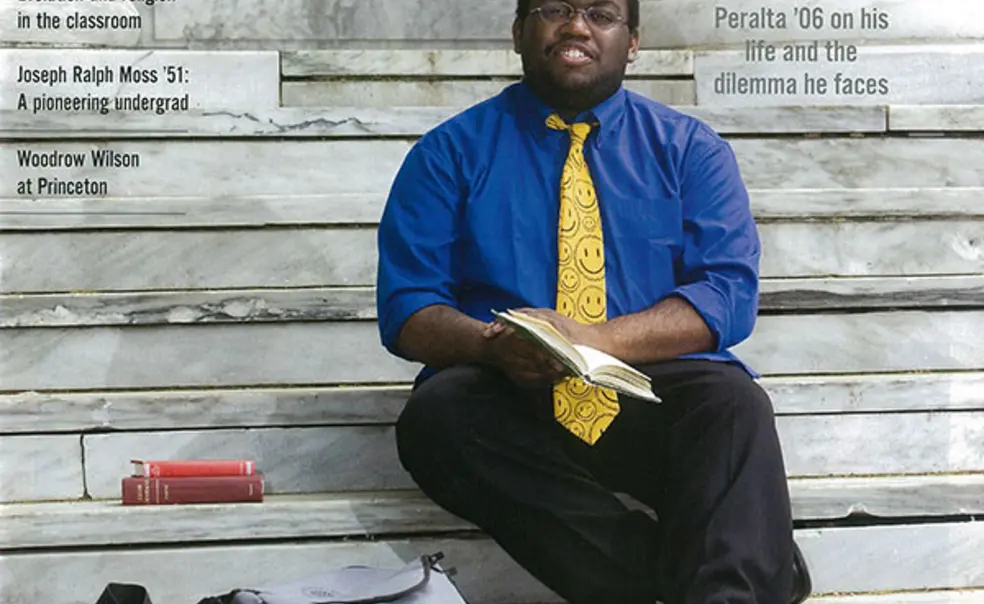

Dan-el Padilla Peralta ’06, the Latin salutatorian at Commencement in 2006, received the Daniel M. Sachs Class of 1960 Graduating Scholarship. This essay was published the week after his graduation.

One of the virtues of being a student of the humanities is the opportunity to frame one’s thoughts around the meditations and emotions of a tradition. Any tradition will do, but as a classicist — or at least someone who aspires to that job — I am concerned chiefly with the history and literature of ancient Greece and Rome. Through the mediation of generations of thinkers, one’s own personal circumstances and labors become more bearable. Reading Aeneas’ words to his men in Book I of the Aeneid “O passi graviora, dabit deus his quoque finem” (“Men who have endured weightier things, the god will give an end to these things also”) has served to remind me that, no matter what my circumstances, there will be some kind of final resolution that — if things break right — will be in my favor; and that I have endured hard times before and can make it through hard times again. To sample again from the Aeneid: Aeneas turns to his friend Achates after arriving in a foreign land and, gazing at the art of the Temple of Carthage, says, “Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt” (“There are tears for things and mortal affairs touch the mind”). There is something almost starry-eyed about this statement; Aeneas has faith in the notion that among these people whose art he has just seen, there is humanity and a willingness to feel and be touched. We might be hesitant to accept the proposition that lacrimae rerum exist everywhere, but I have carried that hope with me even in times when such optimism appears to be unwarranted. And so it is that the study of classics has intersected with my orientation toward my life and other lives.

This all sounds a little far-reaching, if not grandiloquent. But for many years, classics — or specifically, the opportunities I received to study classics — offered me a window into another world, a kind of respite from the more crushing aspects of the life I was living. Especially in high school, where I began my study of Latin and Greek, the routine of academic work in classics was very soothing to me: first in the form of those slightly odd sounds and seemingly innumerable case and verb endings that I tried to master, next in the contemplation of classical literature that moved me in these strange and rather hard-to-explain ways. I think often of Helen Vendler’s remarks in a Paris Review issue about the importance of poetry: Lyric and verse can be faithful and lifelong companions, personal resources, aids in times of anxiety and distress. Latin and Greek poetry and prose have left an indelible impression on me precisely for that reason.

I am an undocumented immigrant, and I hope in the next few pages to give you a sense of how my life story has shaped my academic commitment and to testify to how that academic commitment has helped me grapple with my life story, make sense of it, and now — on my graduation from Princeton — present it to a wider audience.

I was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on Sept. 17, 1984, and lived there for the first four and a half years of my life. I came to New York City in June 1989 on a temporary non-immigrant visa with my parents. My mother had been instructed by her doctor to come to the United States for prenatal care. She was pregnant with my younger brother and was facing potential complications related to gestational diabetes. After my brother’s birth in November of that year, my mother was released from the hospital, only to be hospitalized again a few days later with a serious infection. This made it necessary for us to prolong our stay in the United States. During and after my mother’s hospital stay, my parents discussed our status problem and tried to address it; my father met with a lawyer and paid a fee to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, but he heard nothing back. My parents’ very poor English and lack of financial resources prevented them from initiating the process to remedy our situation. As a result, we fell out of legal status.

It took my mother several months to recover from the infection, and over the next few years she would fall ill but have no recourse to medical assistance because we did not have health insurance. Meanwhile, my mother’s medical problems forced my parents to give up their jobs in the Dominican Republic. My father and mother resolved to try to make a life for me and my new brother here.

It was very difficult for my father to find steady employment, and he insisted that my mother stay at home to raise us and take care of her health. He found temporary jobs driving cabs, working at grocery stores, ironing at a dry-cleaning shop, selling fruit at a fruit stand, and working in a factory. None of these jobs provided enough money to pay our rent, and we moved around several times over the next three years: from Astoria, Queens, to Washington Heights, Manhattan; to an apartment in the Bronx; to an attic in Corona, Queens; to an apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens; to another apartment, two blocks away. Whenever we moved, I changed public schools, although my parents would try to hold on to each apartment until June so that I could finish my school year without disruption.

In January 1993, frustrated by his inability to hold down a job and tired of life in the United States, my father returned to the Dominican Republic. His last job, at a factory, had left him hobbled with a foot injury. My mother decided to stay in New York with my brother and me. To this day, she says that her guiding reason was my performance in school and her desire to see my brother and me obtain good educations, no matter what the personal cost to her. She took comfort in seeing how quickly I learned English and how much I enjoyed school.

My mother was unable to find employment in the months after my father’s departure and could not pay the rent. We lived off my brother’s welfare benefits (for which he was eligible as a U.S. citizen) and the charity of relatives, but eventually we were evicted from our apartment. In the summer of 1993, a friend living nearby made his basement available to us for two weeks. As we slept one night, some exposed piping burst and the basement was flooded with water; my mother woke up as the water was rising and whisked us out of the basement. Most of our paperwork and documentation was destroyed, although my mother managed to salvage our passports and some important papers. For me, the most depressing aspect of the episode was the destruction of a small book of drawings of snakes that I had spent several weeks putting together. I was 8, and I did not have much in the way of perspective, nor did I understand my mother’s zeal in wading through the water to recover the papers strewn about as my little book of drawings lay water-logged and mostly destroyed in a dirty corner.

We packed up what few things we had left and went to an emergency shelter in the South Bronx. After two days, we were taken to a shelter in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we lived for nine months. I remember the shelter being an unsafe place, with many people in various stages of recovery from drug addictions. The hallways and rooms were dusty and dirty, which upset my mother both because she always has been a stickler for cleanliness, and because my brother suffered from asthma and the air inside the building aggravated his illness. But one day a charitable soul gave me a book about ancient Athens and Rome, and I was immediately hooked.

Within a few months of entering the shelter, my mother came down with tuberculosis and was taken to Gouverneur Hospital in Manhattan, where she was prescribed antibiotics and released back to the shelter. One night, my mother pulled me aside after my brother had fallen asleep and gave me a talk about what I should do if she were to become seriously ill and die. She told me to take care of my brother and continue doing well in school, no matter whom we were sent to live with or what happened to us. I was 9 years old.

My mother is a devout Catholic, and when my brother and I were small my mother taught us every prayer she knew. I prayed intensely during the winter months of 1993–94, hoping that my mother would get better. I attributed her slow but successful recovery to my prayers. Once she was on her feet again, my mother began to press social workers to move us out of the shelter, and we ultimately were moved to an apartment in central Harlem. But for three months in between, we stayed at a Brooklyn shelter run by the Salvation Army. There, a young man named Jeff Cowen, who worked with an art program that reached out to children like me, took me under his wing. Cowen encouraged my mother and me to apply to elite New York City private schools, and over the next few years, he helped me submit applications and arrange admission interviews. Thanks in large part to his efforts, I was admitted to the Collegiate School on Manhattan’s Upper West Side for seventh grade.

Collegiate opened many academic doors for me through its rigorous and broad education. It nurtured my nascent interest in classics, and I began to study Latin in the eighth grade and Greek in the ninth. It was very reassuring, after years spent moving around from school to school, to have a place that I knew I would come to every day, to study the things I loved. Though we moved two more times — our central Harlem apartment building was declared uninhabitable and the families were relocated — I was able to continue my studies at Collegiate.

By my junior year at Collegiate, I had begun thinking about colleges and had met with the college guidance counselor a few times. No one discussed my immigration status issue until I brought it up with a few school administrators in conversations about my future. They immediately offered support, and my college guidance counselor encouraged me to apply early decision to Princeton, which I had visited a few times. I knew that I would be ineligible for any federally funded financial aid program, but I hoped that Princeton would look at my application on its merits and not consider my status. I was aware of Princeton’s generous financial aid program. On a cold December day in 2001, my mother called to say that a large envelope with an offer of admission was waiting for me at home.

The rest, as they say, is history. I am majoring in classics with a certificate in the Woodrow Wilson School, and have had the opportunity to follow some eclectic academic interests across the humanities and sciences. I have received many honors, including the Daniel M. Sachs Class of 1960 Graduating Scholarship, which I hope to use to study classics at Oxford University next fall. This may not be possible. Because of my undocumented status, I cannot re-enter the United States for 10 years if I depart for Oxford. At the same time, I have no prospects for employment or graduate work in the United States: I cannot work legally, and no Ph.D. program that requires teaching can support my studies. With Princeton’s help, I was set up with an immigration attorney, Stephen Yale-Loehr, who helped me file an application with Citizenship and Immigration Services (successor to the I.N.S.) in April, arguing that the extraordinary circumstances of my childhood impeded my mother and me from normalizing my status. Since The Wall Street Journal told my story in April, Princeton alumni have supported me in many ways, from calling members of Congress on my behalf to helping me pay my legal fees. Former Sachs scholars, in particular, have been extremely gracious.

My mother and my brother, meanwhile, are carrying on. My mother volunteers with a Catholic group that draws its members from churches in northern Manhattan. My brother is now a junior at the Riverdale Country School in New York City, and is readying himself to apply to colleges in the fall.

The national immigration debate is not merely something I watch on television; it is personal. I had been wary of disclosing the details of my status problem to my friends, in part because I have seen that the words “illegal immigrant” tend to arouse a visceral reaction in people. I have had several conversations over the last four years with students who are vehemently opposed to illegal immigrants — who see them, at best, as an onerous weight on American citizens or perverse riffraff who deserve their place on the margins of society and should be deported as soon as possible. A recent debate on the black men’s student blog — an online discussion board for black men on campus — has cast the hostility to undocumented aliens into sharp relief. In response to the posts of various students examining the pros and cons of several immigration bills being considered by Congress, a former roommate of mine wrote that illegal immigrants constitute a drain on American resources and a threat to the jobs of native American workers; that they are intentional law-breakers who should not receive considerate treatment from the government; and that existing laws concerning illegal immigrants should be rigidly and more consistently enforced, even if this results in behavior that could be characterized as inhumane.

I was taken aback by his words, but they provided me with the impetus to speak out and emphasize the inhumanity of such a perspective as well as the misinformation it is based upon. That is not to say that the thoughts expressed by this classmate represent the main currency of the debate on campus; undergraduate and graduate students from various campus organizations have joined with faculty to champion reform of the immigration system and its laws. I think there are many powerful and cogent arguments that should make people from all walks of life, from average Americans to high-level politicians, revisit their preconceptions of who illegal immigrants are and what they are capable of accomplishing if given the right opportunities.

But I also feel that the debate about illegal immigrants will be resolved not in people’s minds but in their hearts. Part of my motivation in presenting my life story to you, the readers of the Alumni Weekly, is that you will understand my personal experience of illegal immigration. I have tried to work as hard as I can and accomplish what I can, given my circumstances. I hope that my story will make you conscious of what it is to be an undocumented alien. I write in the faith that my words can move you and that there are in fact tears for things, however naïve that faith may be.

“Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit” (“Perhaps it will be pleasing one day to remember even these things”), Aeneas tells his men in Book I. And perhaps, one day, in a future that is more secure, I will look back on the past, recall all the support I received, and smile out of pleasure and gratitude.

No responses yet