The Ph.D. Job Hunt

University puts more emphasis on help for those seeking nonacademic careers

The University is increasing its focus on advising and placement services for graduate students as the job market for teaching positions continues to be challenging.

“The number of Ph.D.s granted nationally has been increasing, but academic jobs are not increasing at the rate of Ph.D.s,” said Sanjeev Kulkarni, dean of the Graduate School. “We need to talk about positions outside the academy not as a second-class option.”

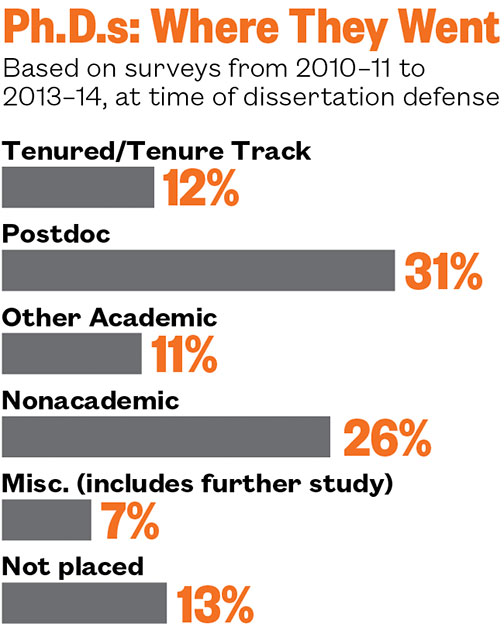

Princeton “does an amazing job at placement, especially compared to national averages,” Kulkarni said. In surveys taken of the University’s Ph.D. students over the last four years, 87 percent reported job offers at the time of their dissertation defense. That compared to a national average of less than 70 percent for the two-decade period ending in 2012, according to a National Science Foundation study.

The Princeton surveys found that during the last four years, about one-fourth of Ph.D. recipients in the humanities and social sciences had a tenured or tenure-track position, while that figure was 5 percent or less for the natural sciences and engineering (adding in postdoc positions swells these numbers significantly). Nonacademic positions ranged from 7 percent for those in the humanities to 53 percent for engineers.

Not surprisingly, over the past seven years, Career Services has seen a 63 percent increase in the number of graduate-student appointments and walk-ins, said Amy Pszczolkowski, assistant director and graduate-student career counselor at Career Services.

“Career Services has professionals who have been trained to help students think about their careers, look for jobs, and get positions,” Kulkarni said. “They are involved in activities such as recruiting and job fairs, and that’s not what faculty members typically do.”

Since last July, Career Services has held more than two dozen workshops for graduate students, including “Career Options for Historians” (government, museums, consulting) and “Career Transitions for Graduate Students.” Alumni have been invited to campus to speak to grad students; in one instance in December, Victoria Bjorklund ’73, a University trustee, gave a talk on “Pivoting with a Ph.D.,” describing her path from a doctorate in medieval studies to law school and a position with an international law firm.

The office has organized visits to employers, including Mathematica Policy Research in West Windsor Township and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in New Brunswick. “I felt the need for graduate students with no experience outside of academia to see where people physically work,” Pszczolkowski said. “It’s tremendously helpful for them.”

Kulkarni cited a pilot program last semester in which four grad students “shadowed” Princeton administrators for about six hours a week, receiving a small stipend and mentoring about university administration.

Career Services also formed an advisory board of 11 grad students last summer. “I think we’ve made some great strides in the past seven years, but I think there’s always room to improve,” Pszczolkowski said. “It’s a work in progress.”

Kulkarni pointed out that academic departments often have field-specific insights into industry; for example, the chemistry department can be helpful when students are thinking about the pharmaceutical industry. But while students often look within their departments for help in finding a job, the reactions of faculty members vary.

Some faculty advisers are very supportive of grad students who want to pursue nonacademic careers, said Sean Edington, president of the Graduate Student Government, but fellow graduate students have told him that others can be “openly hostile.”

“If you’re a professor here, it’s a given that you went an academic route, so some professors might view it as going against what they chose,” Edington said. “It can seem like a snub or a criticism.” In some departments, he added, the academic route is considered the hardest and most prestigious option, and students who do not follow that path can be seen as “giving up or copping out.”

During a discussion of grad-student careers at the March 9 meeting of the Council of the Princeton University Community, philosophy professor Elizabeth Harman asked if the University has plans to encourage faculty to be more receptive to students who are considering nonacademic careers, saying those students can face “real obstacles.”

Sarah-Jane Leslie *07, a philosophy professor who chairs a working group that is examining the Graduate School’s placement and professional-development efforts as part of the University’s strategic planning, said the group may create a set of best practices to support interest in both academic and nonacademic jobs. Faculty members need to “stay abreast of the current job market in their field,” she said, and be willing to be supportive and direct students seeking nonacademic careers to Career Services for help.

Leslie said she hoped the CPUC discussion would help to raise awareness and lead to a campuswide conversation. “We faculty need to take the lead on changing to make sure students feel comfortable exploring the full range of career options,” she said.

“This is a conversation we need to have, and a culture change may be needed in some areas,” Kulkarni said.

No responses yet