Ph.D.s Increasingly Consider a Life Outside the Ivory Tower

Alumni on staff say grad students should think about careers other than tenure-track faculty roles

As Jill Stockwell *17 started her Ph.D. in comparative literature at Princeton, she was still debating her post-graduation plans: To be a professor, or not to be?

While she pondered that question and pursued her studies, Stockwell also volunteered to teach literature and composition with the Prison Teaching Initiative (PTI), a University program that provides education to incarcerated students, and over the course of her degree, Stockwell came to the realization that her work at PTI “needed to be more the focus of my career and not the ‘side thing’ that I was doing.”

Aside from a year-long break to pursue a Fulbright fellowship, Stockwell, who is now director of PTI, has been doing just that ever since.

“I don’t regret not becoming a faculty member, and I don’t regret getting a Ph.D.,” said Stockwell.

Stockwell is one of many Ph.D. holders who are increasingly pursuing career paths outside of tenure-track faculty. According to Nature, “In 2021, more U.S. Ph.D. graduates were hired by private companies (43%) than by academic institutions (36%).”

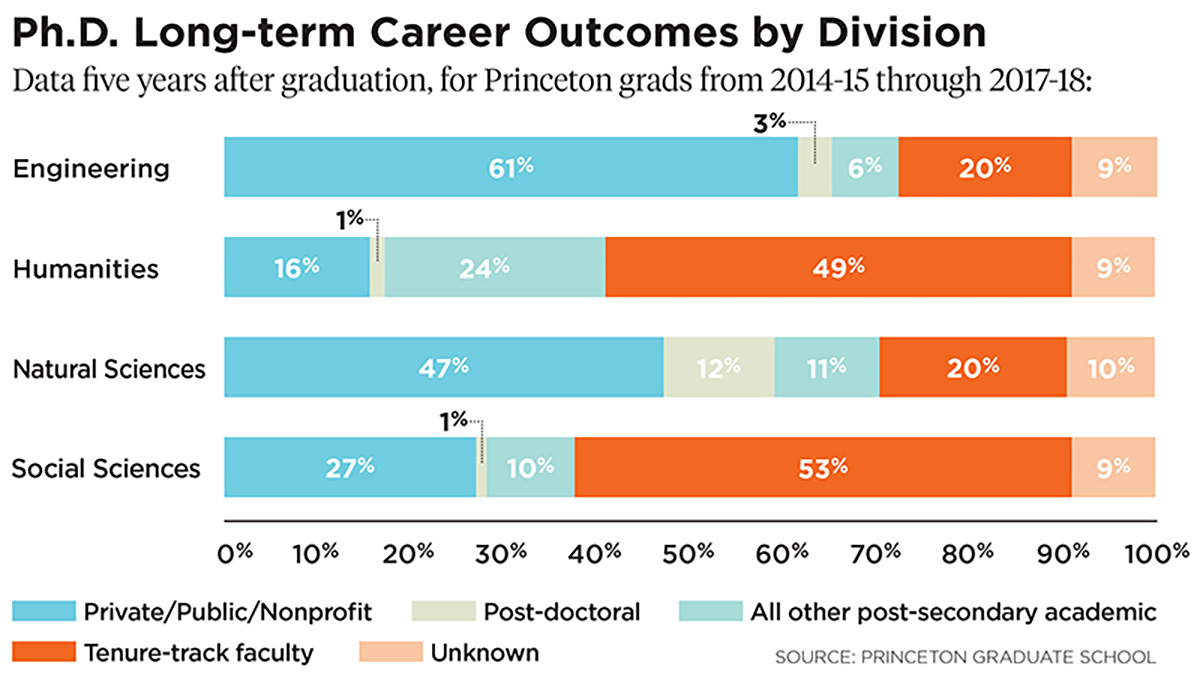

Statistics from the Princeton graduate school show that five years after their graduation, 33% of Ph.D. graduates from the 2014-15 to 2017-18 academic years (the most recent available data) have gone on to become tenure-track faculty. When looking at careers 10 years post-graduation, 43% of Ph.D. alumni who earned their degrees between the 2009-10 and 2012-13 academic years are now tenure-track faculty.

James Van Wyck, who holds a Ph.D. in English from Fordham University and is Princeton’s assistant dean for professional development at the graduate school, said during his Ph.D., tenure-track faculty positions were “something that you are trained to want as a graduate student, and so you believe you can’t pursue life of the mind beyond the tenure track.”

But that’s changing. In the 2022 book Leaving the Grove: A Quit Lit Reader, Van Wyck wrote that “all signs point to more blended careers for Ph.D.s, who will hold administrative as well as teaching positions, or move between higher education and other employers. Such careers feature not binaries or barriers, but interwoven communities and overlapping ecosystems … .”

Emma Ljung *12 used her Ph.D. in classical archaeology to create a blended career; for the past decade, she has been a lecturer with the Princeton Writing Program — “I don’t think that there’s a better job for me anywhere,” she said — and gets her “archaeology fix” during the summers as co-director of the Santa Susana Archaeological Project in Portugal.

Ljung said she “might not have actually had the luck of having to reflect [on] how do I want to feel at work every day” had the 2008 recession not hit five years into her Ph.D., which made the academic job market “fundamentally terrifying and scary.” Around the same time, Ljung realized she was more interested in working with smart and excited students than in teaching classical archaeology.

“In hindsight, it worked out very well for me because [the recession] had helped me find my place,” said Ljung.

Deborah Schlein *19, who received her Ph.D. in Near Eastern studies and loves her job as a Near Eastern studies librarian at Princeton, said she thinks “the academy is still grappling with what it means for their students not to go the traditional route and become a professor, besides the fact that jobs are very scarce and the academy’s not doing a great job of figuring out how to handle that either.”

The tenure-track job market has shrunk, in part due to an increase in the number of Ph.D.s awarded; according to the National Center for Science and Engineering, 55,283 doctorates were awarded in the U.S. in 2020, which is almost 14,000 more than the Ph.D. degrees awarded in 2000, and 45,000 more than in 1960.

When he was in graduate school studying history, Alec Dun *04 was focused on the tenure track; it wasn’t until he took on a position within the University’s residential colleges that he appreciated “that process of thinking about the wider picture of what the undergraduates are doing, [and] what the goals and the principles behind those goals were in undergraduate education.”

In his current role as associate dean of the college, Dun teaches a freshman seminar course, which he says “scratches the itch” to teach, but his work primarily focuses on aspects of the undergraduate academic experience.

Dun joined Stockwell, Van Wyck, Ljung, and Schlein in advising those thinking about a Ph.D. and those currently in graduate school to consider careers beyond the tenure-track.

“Fundamentally,” Dun said, “I think having your eyes open to other paths — that seems like the smart thing to do.”

2 Responses

Diana C. Silverman ’87

2 Years AgoIn Faculty Job Market, Poor Pay Also a Factor

Attributing the shrinking of the tenure-track market between the years 2000 and 2020 to a superabundance of doctorates inaccurately omits that the demand for quality college teaching has exploded, as university enrollments have grown by millions, due in large part to the exciting influx of first-generation and nontraditional college students. American universities across disciplines have met the growth of first-generation and nontraditional college students with educators paid poverty wages, which render them largely inaccessible to their students, as they are understandably consumed by their own fight against food and housing insecurity.

Advising newly minted doctorates to abjure teaching, in effect, means remaining silent in the face of the millions of college students subjected to educators living in the conditions of poverty that obstruct and interfere in every aspect of campus life.

Donald R. Kirsch *78

2 Years AgoOutside the Academy

Thank you for the PAW article “Ph.D.s Branching Out” (On the Campus, January issue). When I was a graduate student the only acceptable career choice was a tenure-track academic appointment at a high-quality research-based university. One of my professors told me that if I pursued a different career choice it would waste the valuable effort he had invested in training me.

Hopefully attitudes at Princeton have changed since 1978. I had a career outside of the academy, and I was pleased to read that this is now common. “Princeton in the nation’s service” does not have to mean that every graduate student must end up becoming a professor.