Photography: Capturing Stillness

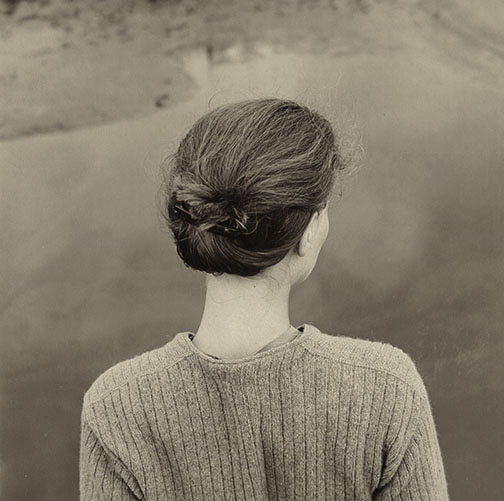

A retrospective of photographer Emmet Gowin’s career displays intimate portraits

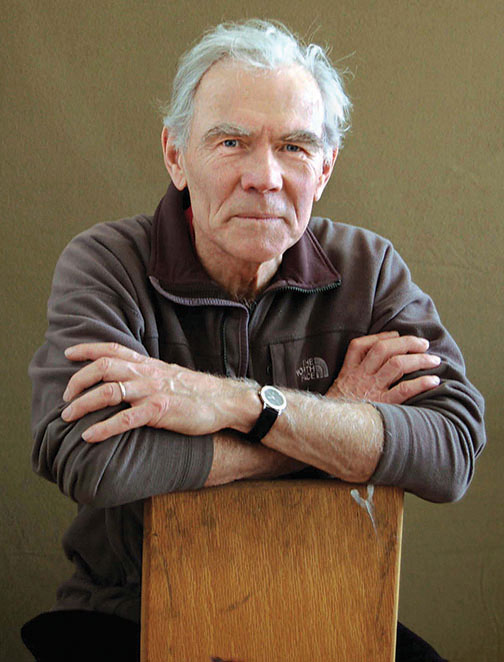

Photographer Emmet Gowin’s most famous photographs have featured scenes both intimate and otherworldly: portraits of his wife and muse, Edith, and explorations of scarred landscapes seen from the air. “I always want to find in a photograph a quintessential stillness,” says Gowin, who retired from Princeton in 2009 after 36 years on the faculty. “Stillness is a most liberating feature in a photograph. It does not feel restrictive — rather, it opens into the imagination, where all our experience is stored.”

The largest retrospective of Gowin’s work to date — 181 of his photographs — was on view earlier this year in Spain and opens in Paris in May. Selected photos will be exhibited Nov. 7–Jan. 4 in New York City. A 255-page catalog, Emmet Gowin (Aperture), reproduces all the exhibition’s photographs. The book captures Gowin’s remarkable range — from photos of frolicking children, to the ancient tombs of Petra, Jordan, to arresting aerial images showing how landscapes have been altered by natural and man-made events. There are ghostly images of Mount St. Helens years after its volcanic explosion as well as photos of the ethereal ponds at a toxic-water treatment facility in Arkansas.

Gowin hasn’t taken much time off since retiring. He has spent several years capturing the beauty and diversity of the many species of moths in Central and South America, which he is assembling into a book that is part children’s book, part scientific guide. Working in the forest at night, he sets up a light to attract the insects and kneels prayer-like over them to depict their natural posture. He says he hopes the photos will convey that “what we do to the Earth, we do to ourselves.”

No responses yet