Princeton Adjusts to Teaching and Learning Dance, Chemistry, and More Online

Professors described students as “shell-shocked” and “highly stressed,” but also relieved to be together online.

Introduction to Contemporary Dance is a class that’s meant to be taught in person.

“It’s a very live class,” said Alexandra Beller, a dance lecturer. “Everything in my syllabus is built for in-class work towards a final public showing of work we make together in the room.”

But when Beller’s class resumed March 23 after the end of spring break, the dance studio sat empty, like every other lecture hall and seminar room on campus, as the University began online classes for the remainder of the academic year.

Beller said the idea of remote learning for her 20-person class was “daunting.” She had to scrap a lot of her original syllabus and make accommodations, like containing all movement during class to a 4-foot-by-4-foot area. Instead of dancing together for the final project, the students will film themselves, and Beller will edit the videos together.

Across all disciplines, faculty members have been adapting their courses for online instruction. Associate Dean of the College Katherine Stanton, director of the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning, was among the University officials who had been preparing for those challenges. When Princeton announced its decision to move to remote learning, Stanton’s team provided guidance on topics ranging from recording lectures and using video conferencing to adapting a course syllabus and compassionately responding to students’ needs.

“I’ve been amazed at the goodwill and the generosity of faculty and students in this transition, in this work,” Stanton said. “People have been incredibly patient.”

Chemistry professor Andrew Bocarsly admitted that he “thought it was going to go horribly” in the first week — like many professors across campus, he was nervous about how he would be able to interact with students while using technology he wasn’t used to. The lectures for his General Chemistry II course were prerecorded to accommodate 150 students in different time zones; problem sets are now submitted through an app; and laboratory experiments are mostly on hiatus (students will analyze data sets for some of the critical labs). Bocarsly said the missing labs are “less than ideal” but won’t hurt students’ learning in the long run.

“Obviously there are a few roadblocks, but on the whole I’m impressed by the professors’ and students’ adaptability to this situation.”

— Priyanka Aiyer ’23

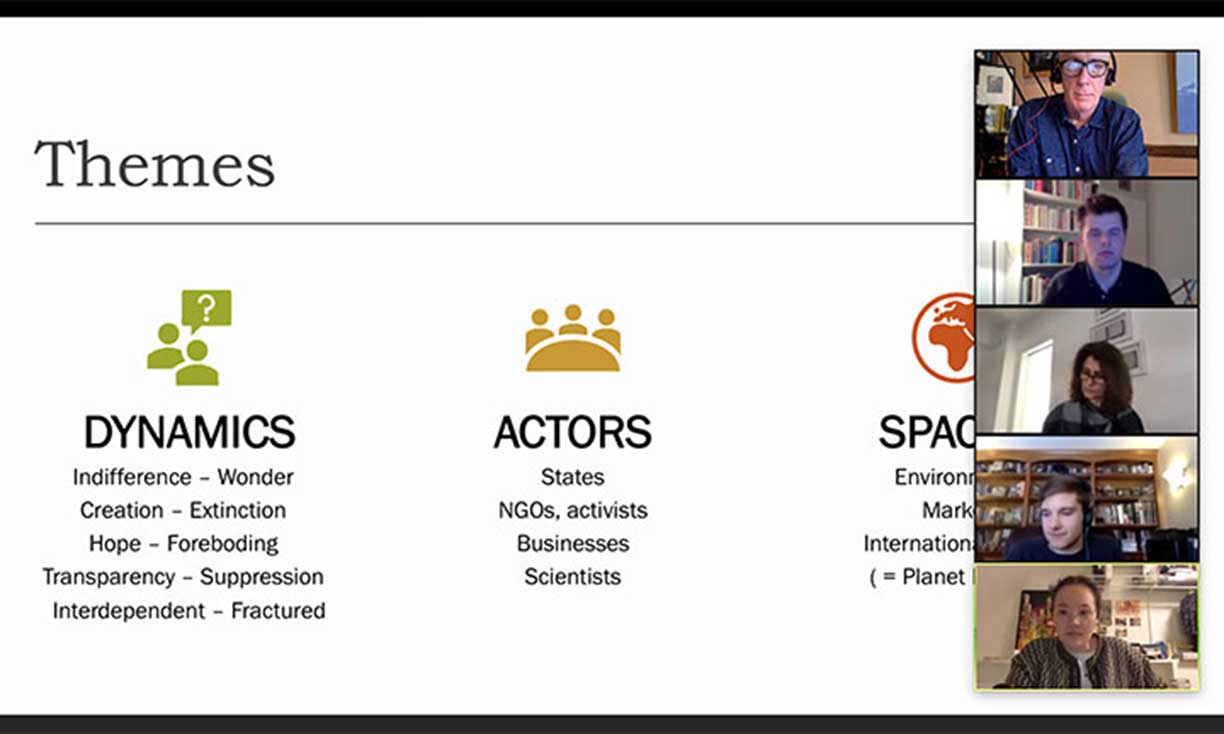

History professor Jeremy Adelman has been teaching a widely popular lecture in conjunction with the online education platform Coursera since its founding in 2012. He said he’s been able to apply some of that experience, but he also had to adjust this semester since he’s now teaching a three-hour seminar instead of shorter Coursera lectures. He quickly found that the time makes a difference in keeping students’ attention remotely, so he has taken to encouraging more conversation between students and allowing additional time for breaks.

“We’re a tough group,” Adelman said about his class. “They all learned they have to go to a quiet place, get some decent headphones, proper lighting, and Wi-Fi, and we’re set to go.”Professors described their students as “shell-shocked” and “highly stressed,” but also relieved to be able to be together again in this capacity and understanding of the circumstances. Students who spoke with PAW had similar feelings after the first week.

“The transition to video classes has actually been quite smooth,” said Priyanka Aiyer ’23. “Obviously there are a few roadblocks, but on the whole I’m impressed by the professors’ and students’ adaptability to this situation. I feel like we’re all doing the best we can, and I’m adjusting pretty well for that reason.”

Jennifer Hsia ’21, who left campus to return home to Taiwan before border restrictions went into effect, said the 12-hour time difference between home and school means classes take place in the middle of the night. She can keep up with her online lectures, but her drawing class has “taken a hit,” she said, even with the separate one-on-one class session offered by the professor. “She said we could show our drawing to the webcam, but there are so many details that are lost in the process,” Hsia said.

One week into “virtual instruction,” faculty members were continuing to learn and make changes for the rest of the semester. Universities around the world are going through the same experience, so there is global camaraderie, commiseration, and an abundance of resources. And professors said that the lessons of this experience will affect the way they teach in-person classes in the future.

“There will probably be some good that comes out of this in terms of new ideas and new concepts for teaching,” Bocarsly said. “There are certainly things to be learned, but right now I’m just trying to cope with the day-to-day.”

By Anna Mazarakis ’16 with reporting from Maya Eashwaran ’21

No responses yet