Princeton Researchers Show How a Conventional War Can Turn Nuclear

The Science & Global Security team had no idea how relevant their simulation would be years later

In 2017, a group of Princeton researchers gathered in a conference room to work on war simulations for an exhibition about the peril of nuclear weapons. They called the project Plan A. At the time, then-President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un were inching up rhetoric around nuclear weapons, and people were feeling uneasy. Instead of looking east, the researchers created a scenario that focused on Europe. Later, they produced a four-minute YouTube video describing their simulation.

Now that work has taken on a life of its own amid growing worry about nuclear weapons in the war in Ukraine. As of April, the video had been viewed more than 3.2 million times.

“The scenario that we discuss in the video now feels quite plausible, and I’m getting a lot of questions and comments about the assumptions we made,” says Alexander Glaser, a co-director of Princeton’s Science and Global Security group. Glaser adds that the simulation is not meant to be a forecast or the most likely outcome of war. Instead, it is designed to explain how countries can go from conventional war all the way to the worst-case scenario: a global thermonuclear war.

While those who grew up during the Cold War years likely remember the fear and anxiety around the possibility of a nuclear war, “nuclear weapons now appear a thing of the past,” Glaser says. “I hope this video encourages a debate on how we can go from A to Z.”

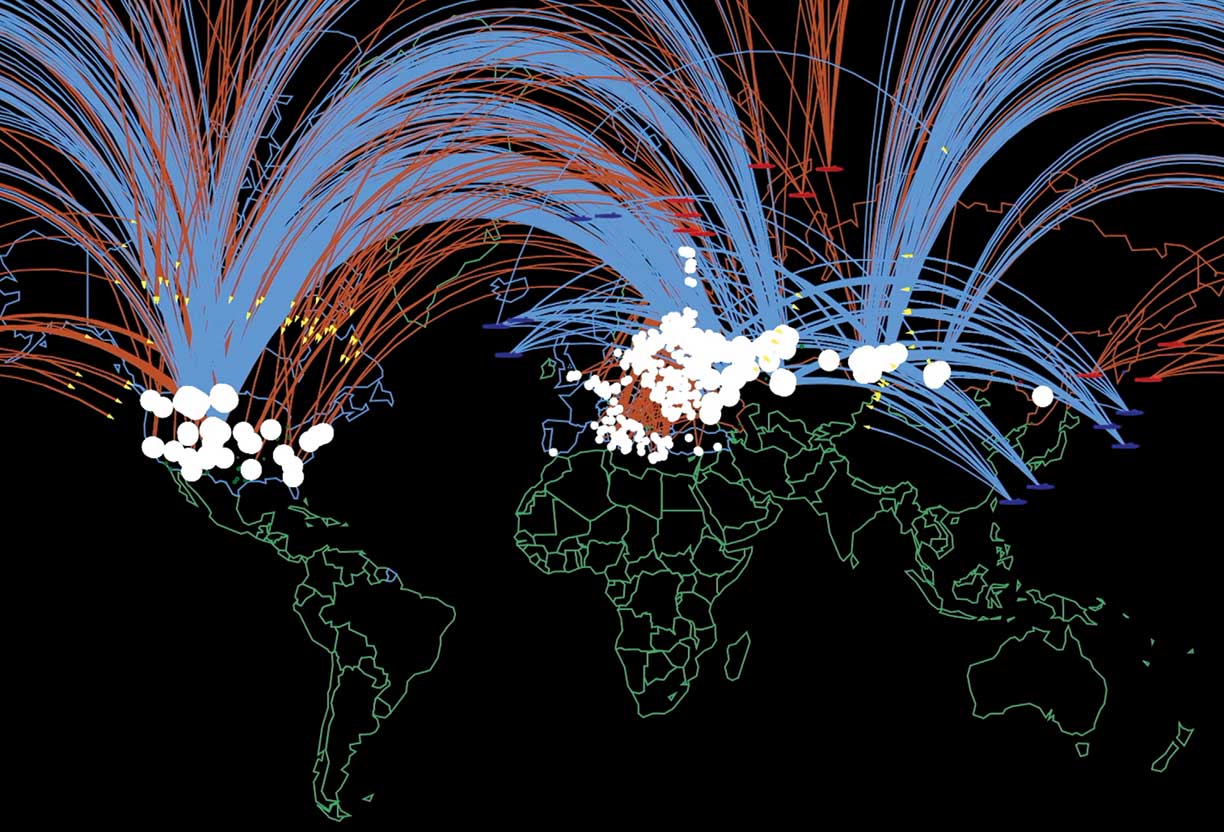

The scenario starts with a dispute between NATO and Russia, with Russia launching a nuclear warning shot from a base near the city of Kaliningrad. NATO responds with a single tactical nuclear air strike. Russia then sends 300 nuclear warheads and short-range missiles to target NATO bases, and NATO responds with 180 warheads, killing 2.6 million people.

From there, the war escalates further, eventually engulfing most of the northern hemisphere within hours of the first shot. Both sides start attacking each other’s cities, with the idea of inhibiting recovery after the world war ends. The researchers estimated that there would be more than 90 million people dead and injured within the first few hours of the conflict.

The researchers used real force postures, fatality estimates, and targets, using data from NUKEMAP, a project by a Stevens Institute of Technology professor that calculates the effects of a nuclear bomb detonation. The researchers say their fatality estimates only include immediate deaths from nuclear explosions; nuclear fallout and other long-term effects would increase the numbers. Glaser says he remembered punching the coordinates for Princeton into a spreadsheet detailing one of the attacks; any city with a national laboratory could be a target for nuclear strikes. “It was a very uncomfortable exercise,” he says.

Glaser’s takeaway from the experience is simple: It doesn’t matter who fires first. The initial strike is the most dangerous one. A low-yield nuclear weapon is not insignificant.

“There’s a connection from where we are now to the unthinkable: an all-out nuclear war,” he says. “It’s important to stop such a war at the beginning, before the first nuclear weapon is used. We have to be paying attention right now.”

No responses yet