Psychology: Baby Steps for a Baby Lab

A new facility will examine how the infant brain develops, one cute kid at a time

The academic buzz that normally fills Peretsman Scully Hall will be mixed this spring with a sound that’s new to the Princeton campus: the pitter-patter of little feet. Princeton’s psychology department is expecting ... a Baby Lab.

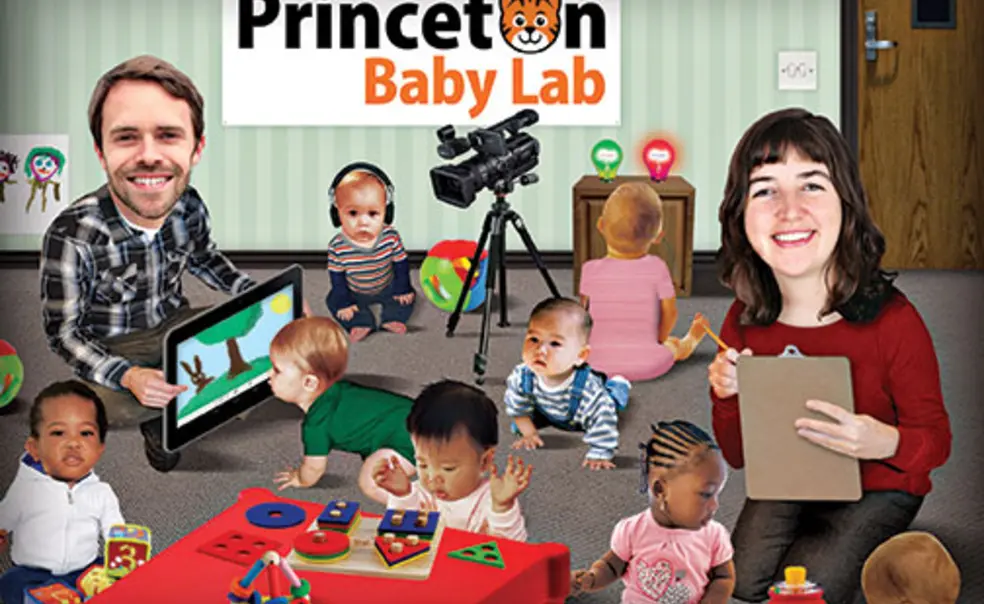

Two new psychology professors — Casey Lew-Williams and Lauren Emberson — are creating what will be called the Princeton Baby Lab, building the University’s role in the field of developmental psychology. “We don’t have a lot of information about how the infant brain works moment to moment, let alone over time,” Emberson says.

Construction of the facility, which will occupy part of the second floor of Peretsman Scully, was scheduled to begin shortly after the first of the year and to be completed by April. A temporary website is up (http://princetonbabylab.wix.com/home), and Lew-Williams and Emberson recently unveiled a Baby Lab logo after an online competition in which they received 134 submissions. It would be safe to say that of all Princeton’s websites and logos, these win for adorableness.

Psychologists have studied early childhood development for decades, but technological advances have opened new fields of research into the age-old debate about nature and nurture. Human brains develop at a staggering rate during the first several years of life. The Baby Lab’s co-directors want to learn how.

Lew-Williams ran a childhood-development lab at Northwestern University before joining the Princeton faculty this year and is the author of a dozen journal articles on the development of language skills in infancy and childhood. His research aims to “simulate a child’s language experience in lab-based studies and by examining a child’s language experience out in the world.”

Children are bombarded with stimuli from the time they are born. Psychologists believe that cognitive development, including the development of language, takes place as a child learns to focus attention on those stimuli, and many of Lew-Williams’ tests attempt to observe and measure attention, which he believes can in turn open a window into what infants know about sounds, words, and sentences.

In one type of test, known as an eye-tracking study, infants are shown pictures or images while listening to words and sentences as a camera records their eye movement. Researchers measure their attention by what their eyes focus on, and for how long.

In another test, known as a head-turn preference test, a child sits on an adult’s lap in a small cubicle. A green light in front of them begins to flash, and when the child turns her gaze toward it, the light goes off and red lights on a side wall begin to flash. When the child turns to look at the flashing red light, a speaker begins to play words or made-up speech sounds, which will continue as long as the child continues to look at the light. If the child looks away for more than two seconds, the lights and the sounds stop. These tests, Lew-Williams says, “use boredom as a tool” to measure the child’s attention span.

Babies, he writes on the Baby Lab website, “are very skilled at two things: focusing, and getting bored. They look at something if they’re interested, and they look away if they don’t care. We are very interested in what makes babies uninterested, because their boredom has the power to reveal a lot about development and learning.”

Lew-Williams also studies how learning takes place in children from different backgrounds, including those with developmental disabilities, children who live in poverty, and children who grow up in bilingual families or in families in which English is not the primary language. Little research has been done on early bilingualism, and much of what parents think they know may be wrong, he says. “Attitudes against early bilingualism are often based on myths and misinterpretations, rather than scientific findings,” he wrote in “Bilingualism in the Early Years: What the Science Says,” a 2013 article he co-authored in the journal LEARNing Landscapes, which is aimed at educators, parents, and community leaders.

For example, bilingualism does appear to promote cognitive development, but not nearly as much as parents pushing their infants into baby Mandarin classes think it does. It does become harder to learn a second language as we get older, but this is largely because we typically are less immersed in it as adults — or even as adolescents — than we are as infants. A high school student sitting in a Spanish class for a few hours a week, in other words, has nothing on a baby who is surrounded by the language all day. “In the end,” Lew-Williams says, “proficiency comes down to practice listening and looking and speaking, and infants get vastly more practice than adult second-language learners.”

Lew-Williams is interested in learning how poverty, particularly in infancy, shapes cognitive abilities. To ensure that he has access to children from different cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, whose parents might lack the ability or inclination to bring them to more affluent Princeton, Lew-Williams plans to open a small lab in Trenton.

“Every kid is on their own learning trajectory,” he says, “and we are very interested in how those trajectories develop.”

Co-director Emberson, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Rochester who will join Princeton’s faculty next summer, has spent much of her career studying the development of perception. Adults use memories of sensory experiences to navigate the world; we can spot a familiar face even if it is partly hidden behind a mask, or find our way around our old neighborhood years after we lived there. Infants are not born with this capacity, and Emberson has devoted much of her work to probing how it develops — seeking, as she puts it on her website, “to uncover the interrelationships between perception, memory, and experience.”

Technology can help uncover those relationships. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, for example, can reveal changes in brain activity, as evidenced by changes in blood flow, but it is difficult to use them to study infants because the subjects must remain absolutely still. A relatively new neuroimaging technique called functional near-infrared resolution spectroscopy, or fNIRS, can measure the same physiological changes as an fMRI, but without many of the limitations.

The fNIRS machines can be very expensive — up to half a million dollars apiece, Emberson says — and Princeton’s will be one of the few university psychology departments in the country to use them for studying early-childhood development. In an fNIRS scan, beams of near-infrared light penetrate the skull and, like an fMRI, provide information about blood flow in the cerebral cortex. It is the same technology used in the pulse oximeters that patients wear clipped to their fingers during hospital stays to monitor blood flow — but in an fNIRS device, these lights are woven into a lightweight cap that slips over the child’s head, with long optical wires attached (wireless versions may come on the market soon), freeing the child to play or move around while being studied.

Emberson has conducted fNIRS scans on hundreds of children over the last three years. The scans are approved by the FDA and expose children to less near-infrared light than they would receive in the time it would take to go from a car to the house, even on a cloudy day, Emberson says. Tests typically last five to 10 minutes — about as long as young children can remain engaged. For their effort, participants will receive $10 and what Emberson calls “some Baby Lab swag” like a T-shirt and a tote bag. Parents will not receive individual diagnostic reports on their children’s cognitive development, although Lew-Williams and Emberson say they can help parents find support if they have particular concerns. The professors expect to see as many as 2,000 children in Princeton and Trenton within the first two years.

Lew-Williams believes that the presence of so many small children will infuse a “fresh, youthful energy” in Peretsman Scully Hall. But he acknowledges that the ordered, scholarly atmosphere may be in for a change. “Babies,” he notes, “can be unpredictable little people.”

1 Response

Kent Warner ’47

10 Years AgoExploring Infant Brains

What professors Casey Lew-Williams and Lauren Emberson are starting (“Baby Steps for a Baby Lab,” Life of the Mind, Jan. 7) continues a much-needed understanding of infant brains. I am working in the real world using the results of these studies.

Last year I started 5 Steps to Five, a privately funded demonstration program in Port Chester, N.Y., where the population is 54 percent Hispanic. One elementary school is 90 percent Hispanic. The main focus of our program is to coach the moms to be their babies’ first and most capable teachers. We are starting our second year. We have the exit interviews from last year’s programs. The responses are important in how we have changed the lives of these families. Many had never had books in their homes. We also know, and show the moms, how a baby looks at the source of its mom’s voice as soon as it can focus its eyes. There is much talk of evidence-based evaluation, which is quantitative. Our program must be qualitatively based for the first few years.

The problem we are now working on is how to deliver the program to poor, stressed, and tired moms. When can they find the time to regularly spend even two hours a week in our program? We served about 35 families reasonably successfully in the first year. Now we know more about how to do it. We will continue to deliver the information from many studies to these families in a way that they can improve their babies’ chances of success in school and life.