Psychology: First Impressions

How much can we learn by judging other people from their faces?

It’s advice frequently given before a job interview: To project confidence and elicit trust, look your interviewer in the eye. But how much can we really tell about another person’s character from something as simple as eye contact? Psychology professor Alexander Todorov says we infer a lot of information about personality from other people’s faces, but those conclusions may not be accurate. In fact, says Todorov, who has spent the past decade studying the psychology of the face, our first impressions often are downright wrong.

“If you see a stranger who’s in a bad mood, you might walk away thinking, ‘Wow, that guy’s really a jerk,’” Todorov says. “We make these broad assumptions about other people that may be perfectly correct in one particular moment, but really shouldn’t be generalized.”

Todorov became interested in studying first impressions more than 10 years ago, when he worked on a study about voters’ perceptions of politicians. He asked people who weren’t closely following an election to look quickly at each candidate’s face and decide which one looked more competent. The test subjects were not told they were looking at candidates for political office, or asked to predict the winner. Those they selected as more competent were the winners of their elections about 70 percent of the time, demonstrating, Todorov says, that voting choices are influenced by our gut feelings about which candidate looks like a better leader.

“It showed that voters aren’t as rational as we might think,” he says. “Whether someone looks competent has a really powerful effect.” He has found, too, that we make these judgments instantaneously: Follow-up studies showed people took less than a second to decide whether a face looked attractive, trustworthy, or aggressive.

In one recent experiment, Todorov used computer analysis to isolate the facial characteristics that trigger particular character judgments. These inferences fell into two main categories: trustworthiness (whether it’s safe to approach the person) and dominance (whether the person is strong or weak). Face shape made a difference, but so did the size and contours of the nose, forehead, lips, and chin. People with baby faces were perceived as submissive, while people with more mature features were seen as more dominant. These conclusions were drawn from one fleeting glimpse of a stranger’s face — and they have serious implications for how we interact with others.

“It can be dangerous to rely too much on the face, because these judgments are not based in rational thought,” Todorov says. “It happens in job interviews, it happens with police, it happens with your online dating profile — we look at faces and immediately we assume that we have a window to people’s personalities, even without talking to them or interacting with them at all.”

Todorov is in the early stages of a study about how our instant judgments about faces are connected to our past experiences with different ethnic groups. A person who grows up seeing mostly Caucasian faces, for example, might attach certain meanings to particular facial features — and those meanings may be different for a person who grows up seeing mostly Asian faces, he says.

“Past studies have shown that you tend to like strangers better if they look like someone who’s your friend or family member. A lot of these judgments don’t come from facial features themselves — they come from you,” he says. “How malleable are these biases? Do they change when you’ve been immersed in another culture?”

Todorov’s research points to one major conclusion: We dramatically overestimate the significance of the face. In his latest study, he measured test subjects’ reactions to a series of photos of the same person making different faces. He found that the slightest change in expression could elicit an entirely different reaction in the viewer. Depending on which photos were shown, the same person could be classified as both extroverted and introverted, or both attractive and unattractive. Yet participants used a stable personality trait — such as extroverted — rather than a fleeting emotion — such as happy— to describe the faces they saw. In other words, we might believe that we can judge people’s dispositions from their faces, but all we’re getting is a snapshot of their moods.

“We’re good at reacting to familiar faces, but we’re terrible at accurately judging unfamiliar faces,” he says. “So there’s an irony there: If we relied a little less on faces, we might actually be better judges of character.”

1 Response

David Galef ’81

10 Years AgoReading Faces

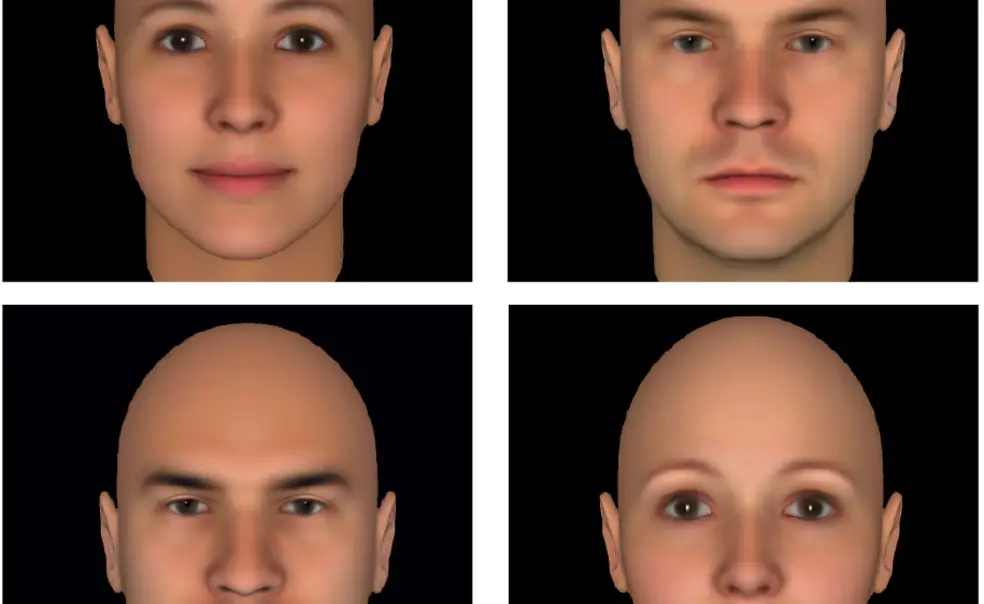

Psychologist Alexander Todorov may well be on to something in how people read faces across the sexes, but the male and female images displayed in “First Impressions” (Life of the Mind, July 8) look more than just male and female. The female image has its lips turned up in a smile, eyes wide, whereas the male image seems to be frowning, its eyes narrowed — or is that supposed to be part of typical male-female differences?