Q&A: Craig Mazin ’92, Whose Foray Into Television Led to a Hit Series

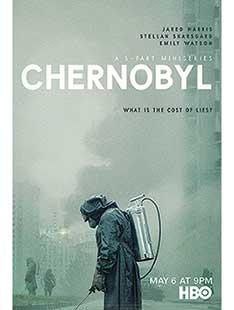

For Craig Mazin ’92, creating, producing, and writing Chernobyl — the gray-hued, meditative five-episode HBO-Sky series about a Soviet-era nuclear disaster — marked a professional departure. Mazin had written several comedy films, including two installments each of the film franchises Scary Movie and The Hangover. He spoke to PAW about Chernobyl, which is nominated for 19 Emmys, and how he came to write it.

What do you remember about the 1986 Chernobyl disaster?

I remember it in the context of the Challenger [space shuttle disaster] three months earlier. Instead of feeling like the Evil Empire screwed up, there was a sense of sympathy. For the first time, we were not thinking of the Soviets as future conscripts in the Cold War, but as people like us.

What we didn’t know, and what we know now, is why it occurred. I also didn’t know how heroically individual people behaved. Soviet communism didn’t work, but the communal spirit of Soviet citizens was very real. It was heartbreaking that people who really did care for one another were so failed by and abused by their own government.

Why did you decide to pursue this particular story?

I had been doing feature comedy from the start, and at some point you become a specialist. But eventually I had enough success that I was able to take some risks with my career.

I went down a rabbit hole researching Chernobyl around 2014. Around the same time, TV became far more flexible in format. I knew the story could not be told properly at movie length, but it also wasn’t right for an ongoing, 22-episode series. So I went to HBO. It wasn’t a huge commitment, so they told me to write the script and see how it looked. I told them the one thing I could assure them is that the plant blowing up would be the least interesting thing. And it worked.

The fact that there was a resistance to truth from within the Soviet scientific community itself. Elements of the scientific establishment actively participated in a cover-up because the truth reflected poorly on them. When you lose science, you’re in real trouble.

It was a combination of hubris and arrogance, but it also stemmed from secrecy and the withholding of information. A safety culture had not been fully established. Under the Soviet system, there was an inability to do things right by the letter of the law, so everybody engaged in this strange collective fiction. That’s how you ended up with the reactor running for a few years even though it had never passed all the tests required to run it in the first place. You had to silently conspire to survive.

Many have commented on how accurate the granular visual details are.

Our costume designers had teams of people rummaging through closets, and we got bolts of vintage cloth for suits. We had an adviser whose job was to make sure any military outfit was correct down to the medals and buttons. Some of the feedback we’ve gotten from people in the former Soviet Union is that it was weirdly nostalgic for them.

Some critics say the story can seem too “Hollywood.”

I disagree with all of it. I don’t think we spent a lot of time on character — no one’s falling in love or dating. It’s about the kind of relationships when you’re in a foxhole together. The fact is, for the vast majority of people who have seen it, they understand our purpose was not to create a pure documentary, but to convey a story by drawing as heavily as possible from truth.

Did the public’s interest in the series surprise you?

We thought people would like it, but we didn’t think it would be a popular hit in the U.S. It’s become HBO’s most-watched limited series since Band of Brothers — 12 million people have watched it so far, which for this kind of series is pretty crazy. It did well for Sky in the U.K., and it’s also done very well in India.

The show demonstrates how government lies can lead to disaster. The role of falsehoods in our politics is a consistent theme nowadays. Is that a coincidence?

The inherent desire to turn away from truth to a more comforting narrative is not new. But this current convulsion is global. You see it in Brexit. It’s happening here, in Brazil, the Philippines, and France, so there is a sense that there is a global war on truth, and narratives are now being weaponized by everyone. I want people to realize the Soviet system didn’t drop from the sky. We have to guard against arranging ourselves in systems where we hurt one another, and really guard against systems that fear the truth.

Interview conducted and condensed by Louis Jacobson ’92

No responses yet