Q&A: Eddie R. Cole Examines Higher-Ed Leadership During Desegregation

From the end of World War II through the late 1960s, America’s higher-education leaders played critical roles in civil-rights issues that ranged from desegregation to housing discrimination. Eddie R. Cole, an associate professor of higher education and organizational change at UCLA, examines the era in The Campus Color Line, a new book from the Princeton University Press that features a chapter about Robert Goheen ’40 *48 in the early years of his Princeton presidency.

What was distinctive about Princeton’s experience with the enrollment of Black students, compared to peers like Harvard and Yale?

In the context of the mid-20th century, Princeton was lagging significantly behind many of its Ivy League peers, when you think of Harvard, Yale, Penn, or Columbia. Princeton did not have a significant number of Black students until World War II, when a particular Navy program assigned a few cadets to the University. As higher-education institutions become more competitive with one another, post-World War II, and you have enrollment skyrocket, there is something to be said about the effort to create a climate that was more welcoming to Black students.

Did President Goheen acknowledge that Princeton had a reputation to overcome?

Absolutely. Being an alumnus, he was very much aware of the campus culture at Princeton. You have a multigenerational lineage of students from the South and the University having a reputation as being Southern-friendly. That doesn’t quite align with the effort to actively recruit more Black students.

Within that context, in 1963 Whig-Clio invited Mississippi’s segregationist governor, Ross Barnett, to speak on campus. How did Goheen handle the event?

Goheen believed that to become a University of the new age, you have to welcome a wide range of thought. With that said, when Ross Barnett is invited to speak at Princeton in October 1963 — only two weeks after the devastating bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and only a year after Barnett had defied the Kennedy administration, which resulted in a very violent desegregation at the University of Mississippi — this is no small feat. Barnett had made a political career out of being anti-Black. To have him come to campus at a time when Goheen is actively trying to recruit Black students — you see the conflict. Goheen publicly condemned the invitation, but he did not put pressure on the students to withdraw the invitation.

What Goheen did was actively work to create campus policies and practices that not only reinforced his statement condemning what Barnett said but also moved the University forward. A number of initiatives went immediately into play. He and other senior administrators started meeting with Black residents of Princeton, who had long felt ignored by Princeton University. They started implementing programs that would actually help Black residents in town as well as Black students coming to campus. So if you were a local real estate agent who had discriminatory housing practices, you were removed from Princeton University’s housing lists. There was an active effort to recruit Black residents for certain positions on campus beyond the traditional menial roles that they’d had for centuries.

Goheen’s biggest action, perhaps, was going before the Board of Trustees on Oct. 25, 1963, and telling them that he could not separate his personal beliefs on racial equality from his responsibilities as college president — his approach was aligned with his beliefs in supporting Black students and Black residents.

Do you think the Barnett episode accelerated the pace of change?

Yes. There was a counterprotest that took place on campus just before Ross Barnett’s speech. Civil-rights leaders such as Bayard Rustin, who is known for organizing the March on Washington, came to Princeton and spoke. What you saw in The Daily Princetonian and other student voices was this public reflection among white students when they saw their college-age peers who were passionate about civil rights come to Princeton to protest against Barnett.

You write about some of Goheen’s contemporaries, including presidents of public universities in the South who resisted desegregation and presidents of HBCUs who helped to disrupt that resistance. How did the role of a college president differ in that era — post World War II through the 1960s — from what it had been in earlier eras?

What we see after World War II is the idea of American democracy put on global trial. The United States had sent military support and fought a war abroad in the name of democracy, yet there was a clear hypocrisy and contradiction in how Black Americans were treated here in the United States. And so with this global crisis happening for federal officials, as well as business leaders and other influential people in the United States, this becomes a major problem that they can no longer deny.

You see the major social issues in the country, and people turn to colleges and universities because they’re supposed to be the places where we can come up with the solutions to very complex problems. In turn, college presidents and chancellors lead the institutions that are supposed to help us come up with the solutions to very complex problems. College presidents really ascended to a new level of public influence during this era. They are tapped by federal officials, corporate leaders, and many others to be the thought leaders around shaping policies and practices that can help address this pressing racial issue in the United States.

It’s difficult to fully appreciate the potential for racial violence on campuses at that time. How were administrators shaped by the riots at the University of Georgia and the University of Mississippi?

These presidents were very much aware of violence, not just in the sense of rioting or destruction of property but losing lives. You can imagine that no president wants to see that happen on their campus. There were no regional boundaries to that potential threat. It wasn’t as if you’re in New Jersey, at Princeton, and you say, “Well that’s an Alabama thing.” No, racial violence was very much an American thing, and college presidents were aware of that. There were students from campuses outside of the South who would be brave enough to go down South and try to be an ally in fighting for equal rights, and they’d lose their lives. Presidents are seeing their students arrested, beaten, or worse.

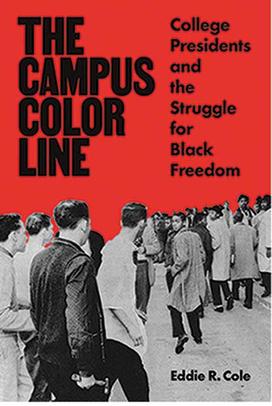

In fact that’s what led us to choose the image on the cover of the book [from the 1960 Congress of Racial Equality publication Sit-Ins: The Students Report], because you see this distinctive color line between a group of Black students and a group of white students — and one white student actually has a hammer in his hand. That’s an image that no college president wanted to see, and that’s the sort of compelling aspect of this moment: There’s a sense of urgency to this work. Robert Goheen could not afford to create a two- or three-year task force to investigate how Princeton could be better on race. And the same thing in Georgia, in Mississippi or California. These leaders were actively, although sometimes quietly, shaping racial policies and practices with a significant degree of difficulty hovering over them and the need to move quickly, carefully, and to a certain extent bravely.

What are the lessons you think we can take away from that period history and the actions of higher-education leaders?

One of the most immediate lessons from this period of history is that we have unknowingly, or perhaps knowingly, accepted the most narrow definition of affirmative action in higher education. And that’s important for us to reflect on because right now when we talk about affirmative action in higher education, we may be talking about two to three dozen colleges and universities across the United States. These institutions are typically majority white and highly selective; but the vast majority of higher education is not considered when we talk about affirmative action.

However, this period in history reminds us that once upon a time, after a national moment of racial crises, we looked at higher education and we had an opportunity to create system-wide change: more institutions well-resourced in a way to expand educational opportunity to more people across every inch of the United States. Yet in reality we saw a significant unfortunate outcome of the original affirmative-action plans, where many college leaders retreated on the idea of systemwide change and turned their attention toward their individual campuses. That’s why today, among the many programs that were initially implemented, many of which focused on historically black colleges and universities, we’re down to the most prominent thought around affirmative action being race consideration in college admissions.

We had an opportunity, in the 1960s, to think about a systemwide change and a more equitable distribution of resources among institutions. And that leads us to think deeply about where we stand right now, following 2020 and another national moment a potential racial reckoning, where we can think again about the opportunity for systemwide change in this country.

Interview conducted and condensed by B.T.

1 Response

Thomas B. Dorris ’64

4 Years AgoWhig-Clio Invitations in 1963

I read the accurate, interesting interview with UCLA professor Eddie R. Cole (On the Campus, April issue) with great nostalgia. The invitations extended to Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett and Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu [the de facto first lady of South Vietnam] were the brainchildren of the president of Whig-Clio, Michael Pane ’64. I was the president of the Debate Panel and therefore one of the directors of Whig-Clio who voted in favor of the invitations. Michael believed that Whig-Clio had become moribund — that it had fallen away from its mission to explore and debate political issues. His program of renewal was a great success.

We had only contempt for Ross Barnett and we felt that he underlined the evil of his ways during his appearance. Madame Nhu spoke only days before the coup in Vietnam that ended the lives of her husband and brother-in-law.

President Goheen ’40 *48’s assistant, a wonderful man named Dan D. Coyle ’38, implored us to withdraw the Barnett invitation, but no pressure or threat of any kind was used. In retrospect, 58 years later, I think the Barnett invitation was a mistake. If my beloved friend Mike Pane was still alive, I believe he would agree.