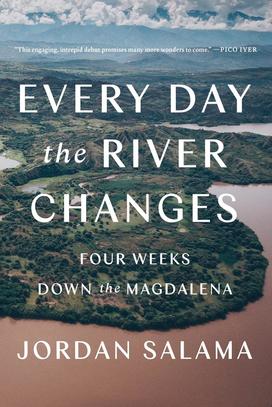

Q&A: Jordan Salama ’19 on Colombia and Writing the 2022 Pre-read

‘At the end of the day, environmental well-being is also human well-being’

How would you characterize the people who live along the Magdalena?

It is hard to generalize, and actually, one of the purposes of this book is place-based writing that kind of shifts away from generalizations and preconceived notions. But what I can speak to are the people who I met and who I included in the book. A common thread that I highlight among almost every single person who I met is resilience. These are tremendously resilient individuals — everybody from social and environmental leaders, who are working to bring their communities out of conflict and towards a lasting peace while also protecting the natural resources of the places where they live, to individuals who spend their lives becoming experts or masters at a single skill or craft.

This is the story of a place that has gone through a lot in the last 50 years or more, and I wanted to provide a snapshot in time of that place through the stories of a few individuals or groups of people who I met along the way.

You write that “Colombia is perhaps the most misunderstood country on Earth.” Can you give an example of a misconception that you had before going there and the reality that you observed?

Definitely. I think that here in the United States, there are few places in the world that we hear worse things about on a regular basis, in popular entertainment, than Colombia. Shows like Narcos and other Escobar-related series and movies really have an impact on people’s conception, and that dynamic is not lost on most of the people I spoke with in Colombia, either.

When I was going for the first time — I was a freshman at Princeton and was going for a voluntary internship funded through the school, with the Wildlife Conservation Society — it was my first time traveling to any foreign country by myself. I thought I would be landing in this perpetually dangerous, horrific conflict zone, where I’d be having to watch my back left and right, because a lot of the times when we’re receiving a limited stream of information, we don’t necessarily realize what everyday life is like for people who live there. And the truth is that when I got there, and throughout my travels in Colombia and along the Magdalena, I participated in people’s lives, immersed myself in their communities. And those days were not, in large part, marked by violence. Perhaps they were at one point, but at the time when I traveled, that was not necessarily the case at the forefront.

That said, there were certainly a whole host of problems in the background, violence being one of them, but people are people and live normal lives and do normal everyday things — flying kites, playing sports, listening to music. And those were the activities that I gravitated toward to make connections and build trust with people to then get them to share their stories about some of the heavier subjects and experiences that provided the meat of the book.

You also write about the environmental situation in the region. What are the primary challenges?

There are so many environmental challenges when it comes to the Magdalena River, everything from contamination to deforestation along its banks, which has caused sedimentation. Now they’re trying to dredge certain sections of the river because it’s so sedimented, which causes another host of environmental problems from disrupting habitat and species that depend on the riverbed for all sorts of purposes. There’s species loss and poaching. There is this sense that the river is far from what it used to be.

Traveling down it, you can almost imagine what used to be there — instead of the cattle pastures and the couple of birds that you see in the sky, you could imagine that it was once heavily forested, with skies filled with clamoring birds and so many fish in the river, manatees and caimans, things that you read about from the past that are so obviously not there now.

And the question is, how did we get to this point, not just in the Magdalena but in so many rivers and natural wild places around the world — and what can we do to bring these places back while respecting the lives and needs of the people who depend on that place?

Did you see glimmers of hope for restoring or preserving the river?

I’ve certainly met a lot of people along the Magdalena who are working on an individual or small-group basis to bring back what they feel has been lost: conservationists and scientists, even fishermen who are trying to work in more sustainable ways while still trying to feed their families. There is a sense that something has been lost and there needs to be work done to recuperate, but there’s this much bigger sense, from a lot more people, that survival is the number one goal. We can’t shy away from the fact there’s a lot of misery and poverty and difficult humanitarian situations along this river. And the question will be how to reconcile the two things.

I think in general, hearing from people who are descendants of Indigenous communities, Afro Colombian communities, who have long lived in beautiful harmony with the land and the water while also taking what was needed for their own survival in years past, their descendants have an especially heightened sense of all that matters for conservation and why it’s so important to protect these bodies of water and the land that surrounds them. Because at the end of the day, environmental well-being is also human well-being. The two things are inextricably linked.

What do you hope your freshman Pre-read readers will take away from the book?

I’ve been thinking a lot about what I want to say to the students when I get to campus and how to kind of frame this book — what universal takeaways for incoming Princeton students can we share from reading a book like Every Day the River Changes? And I think it comes down to this: This book was born from a series of coincidences, where I was either rejected from something or didn’t have some kind of opportunity and decided to take a risk to do something that was a little bit out of the ordinary. One thing led to another, and then I was traveling down the Magdalena River as a rising senior. I think it’s very easy at a place like Princeton to feel pressure to make decisions because you think it’s what you should do and not necessarily what you’re passionate about.

So much of this is also about relationship-building and being willing to start conversations with people who you might not have considered having a conversation with before. And listening deeply — a lot of writing is listening. What led me to be able to write and listen in this way were those conversations that I had on Princeton’s campus, with the other classmates and professors and people who work on campus in all capacities. I would just hope that people are curious and open-minded and openhearted. That to me is the way to make the most of a Princeton experience.

You are the first Pre-read author who was also a Pre-read participant as a freshman. Do you remember anything from reading Whistling Vivaldi, in 2015, and listening to its author, Claude Steele?I remember very well reading the book the summer before school and realizing that I was going to be in a new place, talking with all sorts of new people about that book. And then I also distinctly remember the assembly, where the author came on with President Eisgruber and they spoke for a while. I remember at one point they asked questions to the audience and said, stand up if this happened to you, or if this happened to you — different aspects of our identities and experiences. Some were private, difficult, painful questions, but people still stood up in the crowd in front of everybody. And I thought that was very powerful. So the fact that I’m going to be on that stage with President Eisgruber, not that many years later, is kind of unreal.

Interview conducted and condensed by Brett Tomlinson

No responses yet