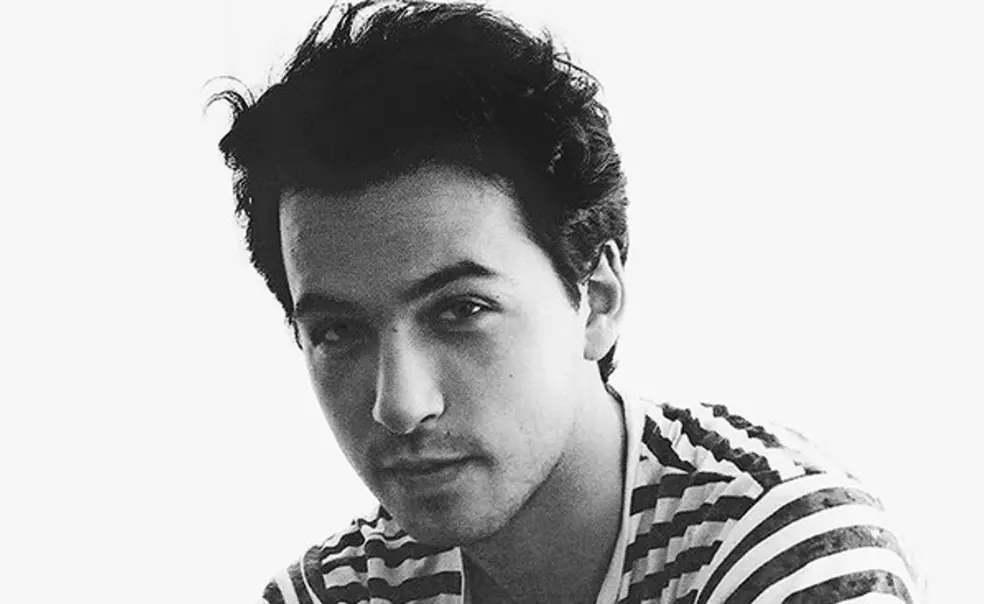

Q&A: Journalist Ben Taub ’14 on His Path to Covering Crises, War

After competing on NBC’s The Voice in 2012, aspiring journalist Ben Taub ’14 saved the stipend he earned and traveled to the Turkish-Syrian border, to learn from foreign correspondents in a region shaped by war. Taub later returned to the border, where he met two Belgian fathers whose sons had run away to join ISIS. Their story would become Taub’s master’s thesis at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism — and a 2015 article in The New Yorker. Now a New Yorker staff writer, Taub won a 2017 George Polk Award for his exploration of environmental and humanitarian crises in the central African region around Lake Chad. He spoke with PAW about reporting in conflict zones.

Your first New Yorker stories were connected to the war in Syria. Why were you drawn to the region?

I followed a girlfriend to Cairo in 2011, during the Arab Spring. She worked for a refugee-rights organization a few blocks from Tahrir Square, and over the course of several weeks I became totally overwhelmed by the feeling that, for the first time, I was witnessing something that mattered. I had no sense of how these events would turn out, only that they were historic. And that was equally electrifying and confusing; I couldn’t speak Arabic, and I had no excuse to pull aside locals to ask about the changes in their neighborhood and their country. After returning to Princeton, I took journalism classes to try to make sense of what had taken place. I began with an investigative-reporting class with Joe Stephens and a foreign-reporting class with Deborah Amos, and then took a year off from school to learn about freelancing.

You traveled to the Turkish-Syrian border in 2013. What did you learn?

My intention was to try to understand how foreign correspondents work by spending time on the fringes of the Syrian war. I lived in a shabby hotel in a small Turkish town called Kilis, about 3 miles north of Syria. Although Kilis is shielded from most of the violence by the international border, from my window I could hear bombings and see airstrikes on the horizon. Ambulances sped up the border road, carrying injured Syrians to Kilis’ hospitals and clinics. Because Kilis is a major crossing point for Aleppo, there were many journalists, aid workers, jihadis, and weapons smugglers passing through it in one direction, and refugees passing through it in the other. My plan was to learn from professional journalists about how they protect their sources, and how they navigate logistical and security considerations for working in war zones.

Instead, as the weeks progressed, ISIS infiltrated both sides of the border, and I became enmeshed in the hostage crisis after an acquaintance was abducted. By the end of that summer, I had learned about security practices in the worst possible way: by watching people get killed for their mistakes.

Is it challenging to describe a situation that many readers know little about, as you did in the story about Lake Chad?

To read Taub’s piece on Lake Chad, go to bit.ly/chad-newyorker.

Lake Chad is the site of a convergence of multiple crises — violent extremism, food insecurity, population explosion, corrupt governance, cross-border aid challenges, cross-border military challenges, a history of coups, and arbitrary, nonsensical colonial borders — all in a region that has been devastated by climate change. This story has been vastly underreported, so there’s even more of a responsibility to get it right — not just in terms of the facts, but also the context and the history. That’s why, after spending a month in Chad, I spent another month poring through historical documents from the colonial period.

How did your time at Princeton influence your path as a journalist?

I had the incredible luck and privilege to spend those years being curious. I majored in philosophy, with a focus on moral gray areas, and that academic path has definitely influenced my journalistic work. I’m not doing anything philosophical, obviously, but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that most of the stories I’ve worked on have started from a place of moral outrage.

Interview conducted and condensed by B.T.

1 Response

Becky Perfect

7 Years AgoAn Incredible Story

I read your article on the Nigerian girl’s trying to escape to Europe. I literally have the first page of the article (all wrinkled up) in my purse because I wanted to ask about what happened to the main girl in the story. I’ve tried several time to message you but didn’t find any link except your Twitter account, which I seem to have forgotten my PW to. Thank you for the wonderful work you do!!