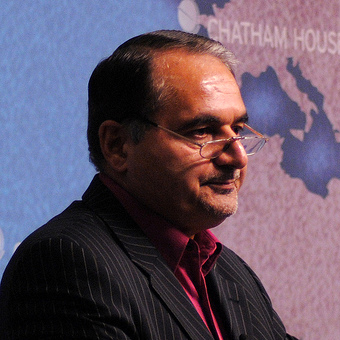

Q&A: Seyed Hossein Mousavian

From 2003 to 2005, Seyed Hossein Mousavian was the chief spokesman for Iran’s nuclear negotiating team. He has served in numerous other governmental positions, as Iran’s ambassador to Germany during the presidency of Hashemi Rafsanjani (1990-1997) and head of the foreign relations committee of the Supreme National Security Council during the presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). Mousavian joined the Woodrow Wilson School and the Program on Science and Global Security as an associate research scholar in 2009 and recently returned to Iran. Before his departure, he discussed the new Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, the recent nuclear agreement with the United States, and the chances of rapprochement between the two countries.

What is the significance of the phone call between President Obama and President Rouhani?

Three unprecedented events happened. The first was President Obama’s speech at the United Nations in September. For the first time since the 1979 revolution, a U.S. president did not threaten Iran and did not use the language of humiliation. After that, foreign ministers from the two countries met face to face for the first time in 34 years. That meeting also was positive and not confrontational. The third step was the phone call.

How important is the new Iranian government to improving relations between the two countries?

A lot. They really want engagement. You will notice that Iran pushed the Syrian government to give up their chemical weapons and to commit to the chemical weapons convention. That was a constructive, positive role. Now Iran is asking the U.S. and the world powers to push the Syrian opposition to give up their chemical weapons, as well.

Why has Iran elected a more moderate government?

I really believe that Iran is a moderate nation with great history and civilization. They want moderate policies. Moderates have controlled the government for 16 of the 24 years since the end of the Iraq war. We had eight years of radical governments which promised to root out corruption. But Iranians have seen that, not only did the radicals fail to stop corruption, the economy worsened and Iran’s international relations deteriorated.

Are you optimistic about a rapprochement with the U.S.?

I hope the U.S. will not miss this new opportunity. I have been involved in Iranian politics since the mid-’80s, and I strongly believe the West lost opportunities with [past Iranian presidents] Rafsanjani and Khatami, both of whom sincerely wanted better relations with the West. Unfortunately, the U.S. decided to pursue a coercive policy instead. Now there is another golden opportunity.

Is Iran’s willingness to reach out a sign that the UN sanctions are working?

When I hear this sort of analysis by American scholars, I am really surprised. Did we have sanction pressures when Iran cooperated with the U.S. in fighting al Qaeda in Afghanistan? Were there sanctions when Rafsanjani secured the release of Western hostages? When Rouhani was the Iranian nuclear negotiator and I was the spokesman, we offered the maximum level of transparency and said that Iran’s nuclear program would always remain peaceful. There were no sanctions then. People forget the history and say that the only reason the Iranians want to negotiate is because of the sanctions.

What was the significance of the agreement the U.S. and Iran reached in Geneva?

It was a great achievement. The world powers accepted Iran’s rights under the nuclear non-proliferation treaty [NPT] to limited enrichment of uranium. They also agreed to lift some of the sanctions. Iran in return agreed not to reprocess uranium and to limit its stockpile of enriched uranium. Each side agreed to two of the other side’s major demands. This was really a win-win.

What are the biggest challenges going forward?

The difficult part still remains. Iran has accepted some short-term limitations of its rights under the NPT as a confidence building measure but going forward, they will insist on their rights. President Obama has said, for example, that Iran doesn’t need a heavy water nuclear reactor. But Iran has the right to build one as a signatory to the NPT.

Now, though, after working together on chemical weapons in Syria and the recent nuclear agreement, Washington and Tehran have seen that they can reach a deal. This will help facilitate further cooperation between the U.S. as an international power and Iran as a regional power on other crises in the Middle East. It shows they can join together to fight extremism spilling over from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

— Interview conducted and condensed by Mark F. Bernstein ’83

No responses yet