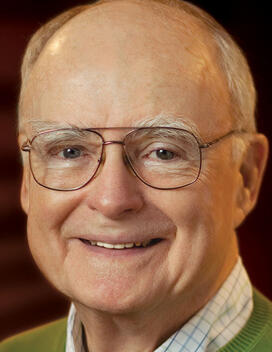

Q&A: William Ruckelshaus '55 on the Watergate Scandal

On Oct. 20, 1973, the so-called Saturday Night Massacre propelled the Watergate scandal into a true constitutional crisis. Confronted with an order from President Richard Nixon to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox, both Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus ’55 resigned. Although Solicitor General Robert Bork fired Cox, a public outcry forced Nixon to appoint a new special prosecutor, and the House of Representatives soon began impeachment hearings, which led to Nixon’s resignation. Ruckelshaus is the last surviving participant in that drama.

Did you have any hesitation about resigning?

No, I honestly didn’t. It seemed to me that what the president was asking us to do was fundamentally wrong. I had worked with Cox when I was acting director of the FBI [from April to June 1973], and he could not have been more cooperative.

What I did was mandated by my oath of office. You don’t resign for light and transient reasons. There has to be some fundamental wrong that the president is asking you to commit before you do that. Firing Cox seemed to fit right within that category.

What did you do that night after you resigned?

My wife and I went out to dinner at the home of some family friends. I got there a little early because my office was closed down faster than I thought. Our children were there, too, watching television upstairs. About half an hour after I got there they came streaming downstairs. One of them was crying, saying, “Dad’s been fired by the president!”

You have defended Bork’s decision to fire Cox. Why?

Both Richardson and I had been asked to promise, during our Senate confirmation hearings, that we would not fire Cox except in extraordinary circumstances. Bork had never made that promise. So there was a difference between his circumstance and ours, which I believed made it justifiable, in his eyes, for responding affirmatively to the president’s order.

He was the last one in line in the chain of command at the Justice Department, and if he hadn’t done it, it wasn’t clear who had the authority to do it. The president could have appointed anybody as acting attorney general and ordered them to fire the special prosecutor.

Is it true that you fired Mark Felt, “Deep Throat,” for leaking to The New York Times?

Felt was the No. 2 guy at the FBI when I became acting director. While he was out of the office on vacation, stories began appearing in the Times about wiretaps that [J. Edgar] Hoover had ordered. We checked and records of those wiretaps were missing from the FBI files, so I started an internal investigation to trace them. After several weeks, we eventually found them in John Ehrlichman’s safe at the White House.

Stories about information obtained from the wiretaps continued to appear in the Times, so obviously there was a leak somewhere in the FBI. I received a call from a man who identified himself as a reporter who was writing these stories for the Times. He said, “I suppose you’re wondering where these leaks are coming from. Well, they’re coming from Mark Felt.”

I confronted Felt the next day. He denied being the source of the story, but I told him I had the information on good authority and didn’t believe his denials. He had violated every stricture at the FBI about the sanctity of information in their possession, that you don’t release that to the media, ever. The next morning, Felt had his resignation on my desk, which I took as an admission of guilt. Years later, Max Holland interviewed me for a book he was writing about Felt. Holland told me he didn’t think I had actually been talking to the Times reporter.

Do you see Felt as a hero?

Oh, no. I think Felt was a guy obsessed with taking Hoover’s place as FBI director. He was trying to feather his own nest and undercut his bosses at the FBI.

To what extent is Watergate responsible for our current cynicism about government?

It certainly contributed to it, but I think it started with the Vietnam War. Trust in government spiraled downward during the war, and things like Watergate gave it another shove in that direction.

You were the first director of the EPA. Has the agency been a success?

I think the EPA has to a certain extent been the victim of its own success. Compared to where we were in 1970, the air and the water are appreciably cleaner. Today there are two to three times as many automobiles on the road, yet the pollution associated with them is appreciably less than it was 40 years ago. We’re not home free by any means. The environment is not something you can clean up, brush your hands, and then walk away from. You have to stay everlastingly at it.

Do you think the EPA interferes too much in the economy?

There are specific examples where the agency has probably overreached, but to condemn the whole effort on the grounds of some of these horror stories is unwise. In order for us to continue to prosper economically, we’ve got to be able to control these unwanted side effects of development. You have to have rules to do that, even in a free society. We can’t expect one company in an industry to live up to high standards of environmental cleanliness if its competitors aren’t forced to do the same things. The only place you can set those rules is in the government.

When Congress gives the EPA these mandates and then stands back and does nothing but complain when the agency carries out its wishes, it’s unfair to the agency and distorts the public’s view of the role of government and the meaning of freedom. Freedom is not the absence of restraints. That’s license. Freedom is a system of restraints. And the EPA is trying to create that system so people can compete within it. Freedom then becomes possible.

Interview conducted and condensed by Mark F. Bernstein ’83

No responses yet