A Raisin in the Sun was the first play written by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway. When it opened in 1959, it made an instant celebrity of its author, 29-year-old Lorraine Hansberry. In the six decades since then, the play — a moving exploration of the struggles of an African American family — has become the most-produced play by a black woman. James Baldwin wrote, “Never in the history of the American theater had so much of the truth of black people’s lives been seen on the stage.” But less than six years after her wildly successful debut, Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer.

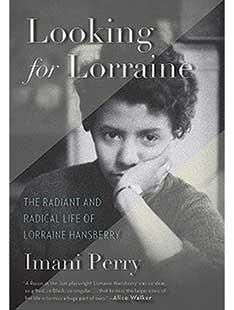

Hansberry loomed large in the childhood of Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies, whose father adored the playwright’s work and admired her political activism. As an adult, Perry wondered why so little was widely known about the groundbreaking playwright. In her new book, Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Beacon Press), Perry explores the connections between the writer’s interior life, her work, and her political engagement.

Her datebooks also shed light on Hansberry’s sexuality. She was married to Robert Nemiroff, a Jewish communist, but joined one of the nation’s first lesbian organizations. In side-by-side lists in her 1960 datebook titled “I like” and “I hate,” she wrote “my homosexuality” in both columns. Her other likes (“my husband — most of the time”) and dislikes (“my loneliness,” “silly women”) are amusing and revealing. “Even this exercise in simple accounting became poetry,” writes Perry. Examining the short stories Hansberry wrote for lesbian magazines, which were published under a pen name and have not been written about extensively before, Perry finds a more lyrical writing style than in Hansberry’s other work: “It was a space for a different kind of voice to emerge for her.”

Perry also explores Hansberry’s devotion to political activism, which prompted the FBI to put her under surveillance during the McCarthy era, when she was in her early 20s. Hansberry played a pivotal role at a 1963 meeting convened by Robert Kennedy, then attorney general, with prominent African Americans in the wake of racial turmoil in Birmingham, Ala. Kennedy had called the group together to get their help in quelling the upheaval, but Hansberry “turns that on its head and says to him, ‘Actually, we want a moral commitment from you on civil rights.’ ”

Less than a month later, President John Kennedy gave his landmark civil-rights address, in which he spoke of the rights of African Americans as not just a legal issue but also a moral one. Perry sees the moment as a crystallization of Hansberry’s drive to make the world a better place. “Once she becomes famous, she uses her fame to support the struggle for justice,” Perry says. “The courage of her convictions was so deep, and she was not intimidated.”

No responses yet